Diabetes mellitus

is a disease that can have significant morbidity if not diagnosed and

treated properly. Diabetes as a disease entity is growing exponentially in

the United States as well as in many European countries.1 The

number diabetics in the United States alone has surpassed the 16 million

mark. In addition, about 2.3 million people may have diabetes and not even

know it. Diabetes mellitus is a condition in which the level of glucose in

the blood becomes too high because the body is unable to process it

properly. This results from either an inability to produce insulin or

because the body has become resistant to the insulin produced by the

pancreas. Insulin is a hormone produced in the pancreas, which controls

almost all assimilation of glucose into the body’s tissues and organs, while

maintaining a delicate concentration of glucose for the body to use.2

All organs and body tissue require glucose for

metabolism and proper function; however, the brain and nervous system are

particularly dependent on and cannot function without glucose. When serum

glucose levels are not maintained within a small concentration, disease

processes often begin.2 When insulin is reduced, glucose levels

remain high in the bloodstream and cells “starve,” as glucose is the main

energy source for body cells. Without the assimilation of glucose, the body

cannot manufacture the high-energy compound adenosine triphosphate (ATP),

the body’s power molecule. When glucose levels in the blood are high but low

in tissue and organs, the body begins to metabolize fatty acids for energy.

This process is much less efficient than the proper use of glucose and leads

to a buildup of ketones in the blood and tissue. The resulting condition is

ketoacidosis and greatly upsets the body’s acid-base balance.1,2

Ketoacidosis can cause both short- and long-term complications.

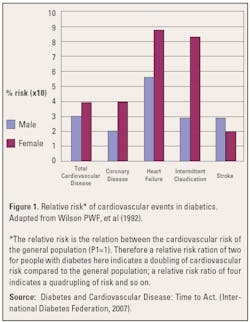

Coronary risk associated with diabetes

Coronary risk is defined as the amount of risk a

patient holds based on several factors.2 Hereditary and genetic factors

cannot be changed or minimized but can be addressed by lifestyle changes and

attention to health status. Risk factors influencing coronary or cardiac

risk include diet, cigarette smoking, age, weight, and lifestyle. Coupled

with this is family history of heart disease and heart attack, which further

amplifies the risk of developing coronary disease.

Studies have shown that patients with diabetes are at

a higher risk for cardiac involvement and cardiac-related risks.3

Research also suggests that patients with elevated hemoglobin A1c (a

component of hemoglobin that is affected in diabetic patients) were more

prone to cardiac risk and heart attack.3 Further evaluation of

patients with diabetes revealed that the risk of stroke was increased

twofold in patients with an elevated hemoglobin A1c level when tested over a

one-year period.3 Figure 1 illustrates the risk of cardiac

involvement in patients with diabetes. In the diabetic patient, due to the

mean increase of glucose in the bloodstream, LDL and HDL cholesterol ratios

are often inverted.4 Cholesterol levels over 200 mg/dL are

dangerous to the general population but more so in diabetic patients.

Increased serum cholesterol levels can lead to rapid acceleration of the

possibility for cardiovascular events.4

Importance of blood glucose and cardiac risk testing

Most routine test panels include a glucose test to

monitor the mean serum glucose levels of almost every patient. In patients

with known diabetes or cardiovascular disease, glucose testing becomes much

more important. Clinical studies have shown that reducing blood-glucose

levels can reduce the associated morbidity risk of cardiovascular disease.

In terms of diabetes testing, hemoglobin A1c is a key indicator of diabetic

control as well as risk of cardiac involvement in acute as well as chronic

events. Hemoglobin A1c, an indicator of morbidity risk in both diabetic and

non-diabetic patients, is a crucial indicator in terms of long-term glucose

management and its relationship to cardiovascular episodes.

During 1990 to 1992, researchers examined data from

the Arthrosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC),5 a

community-based cohort of almost 16,000 people from four states — North

Carolina, Mississippi, Maryland, and Minnesota. A1c levels were taken from

study participants during clinical exams, and patients were tracked for 10

to 12 years for their propensity to acquire coronary heart disease,

hospitalization, and death.5 The study showed a graded

association between A1c levels and increased cardiovascular risk. The final

results showed that each one percentage point increase in the participant’s

A1c level was associated with a 14% increase in heart-disease risk.5

Study researchers determined that an acceptable A1c level ranges between 5%

and 7%.5

Hemoglobin A1c has become, within the past 10 to 12

years, the number one indicator of diabetic control, and is now being

evaluated as a blanket screen for all patients to determine not only

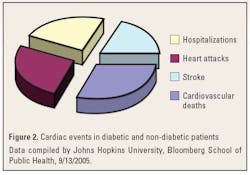

diabetic risk but also cardiovascular-disease risk as well. Diabetes is a

strong risk factor for cardiovascular-event risk. But even in patients

without diabetes, an increase in cardiac-event risk was proportional to an

increase in blood glucose. Researchers tracked 5,484 patients, both with and

without diabetes, and evaluated the effects of elevated glucose levels on

cardiovascular deaths, heart attacks, strokes, and hospitalization for

cardiovascular events. Figure 2 demonstrates the results of this study

conducted by Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg Health Center.5

When researchers examined fasting blood-glucose

levels alone as a risk factor by adjusting for other known risk factors,

they found that, for all patients, an increase of 1 mmol/L above a patient’s

entry glucose level increased the risk of hospitalization by 5%. Similarly,

a 1 mmol/L rise increased the risk of congestive heart failure,

hospitalization, or cardiovascular death by 9% for all patients, by 3% for

patients without diabetes, and 5% for patients with diabetes. Even in the

normal range, results indicate that elevated blood-glucose levels are

associated with the risk of heart failure or death from cardiovascular

events.2

As demonstrated, patients with diabetes are at

increased risk for cardiovascular events and cardiovascular death. Patients

without diabetic involvement, however, still share a considerable risk for

increased cardiac events.5 By testing patients, especially

diabetics, regularly for blood-glucose levels, hemoglobin A1c, and cardiac

risk, physicians have a better overall picture of the patient’s health and

prognosis. By using other potential risk factors, such as current health

status, family history, and lifestyle factors, patient health can be better

managed; and diabetics can enjoy a better quality of life while managing

their disease.

It is difficult to overemphasize the need for

diabetic- and cardiac-risk testing in all adult patients. By testing

regularly for these conditions, physicians are able to better manage

disease, recognize potential negative implications, prevent exacerbation of

current disease, and treat events more effectively. The increase in the

availability of newer and better diabetic and cholesterol-lowering drugs has

added to the arsenal of weapons available to fight these diseases and reduce

the morbidity of diabetic complications.

Richard Peluso, MT(AACC), BSHA, attended Felician

College in Lodi, NJ, and received his MBA in Healthcare Management from

University of Phoenix working as a product manager for Alfa Wassermann

Diagnostic Technologies.

References

- Sacks D, Bruns D, Goldstein D, Maclaren N, McDonald J, Parrott M.

Guidelines and Recommendations for laboratory Analysis in the Diagnosis

and Management of Diabetes Mellitus. Clin Chem.

2002;48(3):436-472. - Dr. Laurence M. Demers, Distinguished Professor, AACC Past

President, Penn State University, Personal interview, (January,

2008) - Lab Tests Online “Diabetes Mellitus.” 2008 Available at

http://www.labtestsonline.org/conditions/Diabetesmellitus.html .

Accessed on August 1, 2008.

Johns Hopkins University, School of Public Health. 2005. High

Blood Sugar Levels: A Risk Factor for Heart Disease. Available at

http://www.jhsph.edu/se/util/display_mod.html . Accessed on August 10, 2008. American Heart Association Health Journal.

Even “High Normal” Glucose Levels May Increase the Risk of

Hospitalization for Heart Failure in People at High Cardiovascular

Risk. Available at

http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=3045833

. Accessed on August 12, 2008.