Investigators from Cedars-Sinai Cancer have discovered that cancerous tumors called soft-tissue sarcomas produce a protein that switches immune cells from tumor-attacking to tumor-promoting. The study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Cell Reports, could lead to improved treatments for soft-tissue sarcomas.

The researchers focused on the tumor microenvironment—an ecosystem of blood vessels and other cells recruited by tumors to supply them with nutrients and help them survive.

“Tumors also recruit immune cells,” said Jlenia Guarnerio, PhD, a research scientist with Cedars-Sinai Cancer, assistant professor of Radiation Oncology and Biomedical Sciences and senior author of the study. “These immune cells should be able to recognize and attack the tumor cells, but we found that the tumor cells secrete a protein that changes their biology, so instead of killing tumor cells they actually do the opposite.”

Soft-tissue sarcoma is a rare type of cancer that forms in the muscle, fat, blood vessels, nerves, tendons and joint lining. It most commonly occurs in the arms, legs and abdomen, and kills more than 5,000 people in the U.S. each year, according to the American Cancer Society.

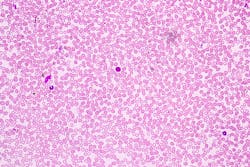

In comparing samples of a variety of soft-tissue sarcomas in humans and laboratory mice, Guarnerio and her team noted that most of these tumors have an abundance of immune cells called myeloid cells in their microenvironment.

To find out what was causing this change, investigators examined the proteins secreted by the tumor cells and the receptors on the surface of the myeloid cells—the elements cells use to communicate. “We examined the cross-talk between these two populations of cells,” Guarnerio said. “We found that the tumor cells expressed high levels of a protein called macrophage migration inhibitory factor [MIF], and that the myeloid cells had receptors to sense the MIF proteins. This makes them switch their biology and promote, rather than block, tumor growth.”

When the investigators generated tumors from cancer cells that didn’t express MIF, myeloid cells were able to penetrate the tumors and tumor growth was reduced.

“This means the myeloid cells might have attacked the tumors directly, or might have activated other immune cells, for example T cells, to attack the tumors,” Guarnerio said.

The investigators believe this information could be used to create novel therapies against soft-tissue sarcoma. A medication designed to stop cancer cells from expressing MIF could be tested in combination with existing therapies, for example, to see if it improves outcomes for patients.