Upper management at commercial and hospital outreach laboratories often spends a lot of time discussing compensation for its salespeople. That’s not a surprise; their function is important, and the best can command high salaries. But lab leaders should not make the mistake of thinking that a willingness to pay more will result in greater success. Appropriate compensation is a motivator, but it does not guarantee results. The sales manager’s (or lab manager’s) oversight and the lab’s strategic objectives are also important parts of the equation.

Labs that hire full time field personnel typically offer a bifurcated payment approach: base salary plus variable compensation. Within that generalization, there can be many differences in approach—and many different results.

Here are some common questions and possible answers that seek to shed light on this important topic. Their purpose is not to recommend a particular compensation (comp) plan, but they may provide food for thought for those who are creating a new payment system or want to reassess their present one.

What are some common mistakes laboratories make in compensating their sales employees?

One mistake is not being acquainted with the “Rule of 78”—the most widely used formula for devising a 12-month sales comp plan. How does this rule work? Management simply multiplies the expected monthly net revenue (or specific test volume) by 78 to arrive at a twelve-month figure. Starting with the first month of expected new business, each consecutive month adds the same pre-set dollar figure (or test number). Moving from left to right, the monthly columns grow longer by a factor of one, since the previous month figure rolls over in a consecutive fashion. The Rule of 78 provides a framework to calculate how new business relates against a pre-set expectation at any point during the year.

Another mistake is beginning the monthly sales goal immediately after hiring a field rep. With new hires (especially from outside the industry), it may be more prudent to begin the sales target several months after the rep’s start date and then insert a monthly gradient increase up to the desired level.

In conjunction with this, another mistake occurs when sales/lab managers may set goals too aggressively within their market. If this happens, field reps may soon become dispirited, and spend more time servicing customers than finding new ones.

Some lab leaders err in a different direction by making the compensation plan too much of a cakewalk. For example, if the sales rep has a “combo” role (sales and service), and if there is a substantial variable payment for servicing and maintaining current clients, the rep can easily become complacent by focusing on “howdy-and-cupcake” visits with current clients. I know of one real-life situation that developed into a thorny issue when lab management (after several years) announced a “peddle-to-the-metal/more-new-revenue” initiative. The lab eventually released the rep involved, but not before paying an above-average base

salary and commission for unproductive calls.

Should variable compensation plans pay for a specific time-period?

In most situations, labs pay a variable rate for a certain time following new account activation—frequently twelve months. I have witnessed some plans that continue payments for two years, but the commission percentage reduces in Year Two. Paying for specific time periods can depend on the lab’s specialty and philosophy. For example, I know one dermatopathology lab that offers a very competitive base salary. For every account the rep activates, the owner pays $2 a biopsy for the life of the client. While $2 may seem modest, the persistent dollar stream—with no calendar endpoint—accrues rather nicely as more clients continue to activate.

What is an example of payout percentage of new business?

Some labs set a graduated scale based on the monthly volume of new business. As an example, the percentage may be five percent for the bottom tier. The next sales level may be eight percent, and the top echelon of new business for the month may be ten percent. The net revenue associated at these levels varies among organizations. However, to give one example, the bottom tier could be $5,000 to $5,999; the middle tier could be $6,000 to $9,999; and the upper level could be $10,000 or greater. In other cases, a lab may institute a simple two-tier structure: a certain percentage for business that falls below the expected new business goal for the month and a higher percentage if the goal is met or exceeded.

Due to the extra expense and, possibly, the strategic direction, some labs do not pay commission on health fairs and/or nursing homes. Other labs may compensate at a reduced percentage rate.

Is it fair to pay reps a commission if they’re not attaining a monthly quota?

I think it is fair. This business of laboratory sales is very challenging, and there are certain times when a field representative will not meet his/her quota in any particular month (or at any point collectively during the year). However, it is psychologically important to reward for any activated business, in spite of the fact that it does not meet a certain monthly or yearly watermark.

Should commissions be capped?

No. Capped commissions can breed sales mediocrity—if only from a conceptual standpoint. Even if a representative knows he/she will probably not achieve the capped segment, cappingproduces a psychological “sales pall.”

Should labs base their incentive pay on activities in addition to new sales?

I’m not in favor of providing additional pay based on the number of visits that a sales or service person may have in a certain timeframe. Upper management typically feels they compensate daily activities through base salary. What needs to occur—and this comes through management oversight—equates to an acceptable balance between efficiency (i.e., activities) and effectiveness (i.e., new business).

For field reps who are strictly assigned to servicing customers, there should be financial rewards for upselling activities.

What about variable comp and upselling activities?

For most labs, upsells are an inherent part of the job and should always be encouraged because they translate to more revenue per client. Some labs separate new accounts from upsells (and pay a greater amount for new accounts); others calculate commissions based on collective sales numbers versus the previous year (i.e., no distinction between new and upsell). There are two types of upsells that can be recognized through a commission plan: 1) by a specific test; or 2) by overall volume.

Labs that compute upsell business should average the previous three months’ net revenue (or specific test) when initially reported by the field person and documented as an upsell. This establishes the foundation. Beginning with the first month of the upsell, they subtract the current figure from the calculated base figure, arriving at the true upsell number for each month.

Should attrition goals be set and a corresponding bonus be paid?

Yes. Losing business is a real-world occurrence, and reps typically put in time and effort to avoid any losses. The definition of a “lost client” remains a lab administration decision. My definition would be when a client’s current month’s net revenue realizes a 50 percent or greater decline compared to the previous three-month’s average. (Client vacation schedules or other variables must be taken into consideration.) One methodology is to divide the year into quarterly payouts and set specific lost-account financial ranges. As an example: pay a bonus of $800 for the quarter if there was no lost business or up to an average monthly revenue of $2,999; pay $400 from $3,000 to $5,999 average lost revenue; and offer no payout if $6,000 or above. The average lost revenue from each account should be applied to the attrition calculation once (i.e., not totaled for the entire quarter).

In client billing situations, should commissions be paid in relation to bad debt?

When receivables reach 120 days old and beyond, any commissions that have been generated from that account should be deducted from future sales commissions. While companies naturally want to avoid Accounts Receivable even at 90 days, labs may, nevertheless, pay commission on these tardy-paying accounts. Going much deeper than that uncoils into a win-lose situation in which the marketer wins and the lab suffers.

Besides the attrition bonus, are there any other sales bonuses laboratories should consider?

Some labs recognize a salesperson’s business and selling acumen when they sell more than $1 million during a calendar year. They may pay a one-time bonus for achieving such a lofty figure, perhaps on the order of $40,000 to $50,000. Some labs combine a one-time payout with an exotic trip destination.

Another bonus consideration involves a quarterly and/or yearly reward. In addition to paying according to the traditional monthly plan, some laboratories compensate using a flat percentage bonus on all new business that exceeds the goal for any given quarter (or for the entire year).

Any final comments?

Commission and bonus plans are intended to help in growing a lab’s business, maintaining its client base, and providing—in some measure—motivation for a salesperson. Additionally, company culture, management practices, and strategic goals will also contribute to how field reps perform. As such, a compensation plan is part of—not a substitute for—ongoing performance-enriching principles.

What are lab orders costing you?

By Aaron Harper, MD, and David Novis, MD, FACP

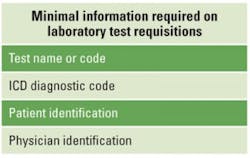

Almost two percent1 of the two billion2,3 test requisitions that laboratories receive annually lack the basic information that clinical laboratory professionals require to perform laboratory tests (Figure 1). This lack of attention to detail delays therapy and costs the medical community millions of dollars each year. A Q-PROBES study (Q-PROBES are short-term studies that provide a one-time comprehensive assessment of key processes to aid in quality improvement efforts in a laboratory) performed by the College of American Pathologists (CAP) showed that two out of every three of these requisitions fail to specify what tests physicians wanted the laboratory to perform, or even the patient diagnoses that necessitated the testing inthe first place. Further, one in every six outpatients arrives at laboratory collection stations without any orders at all.

Patient consequences

The CAP study found that laboratory workers sometimes delayed patient testing for upwards of an hour while they tracked down the information that they required to proceed. In one out of every thousand tests, their efforts were unsuccessful and laboratory personnel had to abandon testing. Worse, some hospitals reported that when they were unable to locate the ordering physicians, their staff completed vacant requisitions by “guessing” at what tests they thought the doctor might want them to perform.

Doing the math

According to the National Inventory of Clinical Laboratory Testing Services (NICLTS), some seven to eight billion laboratory tests are performed yearly.2 A survey performed by George Washington University School of Public Health determined that, on average, a laboratory requisition contains orders for four tests.3 That means that laboratories process about two billion requisitions each year.

Spending as little time as 10 minutes to clarify the 1.8 percent of orders that the Q-PROBES study showed needed clarification would require laboratories to consume more than five million hours of clerical full time equivalents (FTEs). According to payscale.com, with clerical labor values at $13/hour, this results in a waste of approximately $65 million annually.

If you think your hospital has a problem with faulty ordering, it probably does. The Q-PROBES study found that many participants had twice as many defective orders as they expected to have.

What can you do?

The good news is that the Q-PROBES authors offered ways to reduce the number of defective orders and the time that laboratory personnel spend to correct them. Here’s what laboratorians can do:

- Implement policies that require caregivers ordering laboratory tests to verify that requisitions are complete.

- Implement policies that prevent laboratory and hospital personnel from collecting specimens until requisitions contain all essential information.

- Standardize ordering practices throughout the healthcare community.

- Add electronic ordering with the laboratory menu to your laboratory’s capabilities.

As a metric in any quality improvement plan, clinical laboratory professionals track the numbers of incomplete orders, locate the trouble spots, and target remedial actions accordingly.

Aaron Harper, MD, serves as a Chief Resident in Pathology at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, New York.

David Novis, MD, FCAP, is President of Novis Consulting, LLC, providing services to pathologists and medical laboratories.

References

- Meier FA., Darcy T, Steele, JCH. QP092 monitoring of outpatient orders requiring clarification. College of American Pathologists Q-PROBES 2009.

- Steindel SJ, Rauch WJ, Simon MK, Handsfield J. National Inventory of Clinical Laboratory Testing Services (NICLTS). Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 2000;124(8):1201-1208.

- Regenstein M, Andres E. Results from the national survey of independent and community clinical laboratories. November 14 2012. https://www.aab.org/images/aab/pdf/2013/Lab%20Survey%20by%20GWU.PDF. Accessed January 28, 2016.