Physicians, clinicians, and laboratory professionals agree that there is no silver bullet for detecting sepsis, a potentially life-threatening, costly, and complex condition. They also agree that early detection, diagnosis, and treatment are keys to patient survival rates.

What is sepsis?

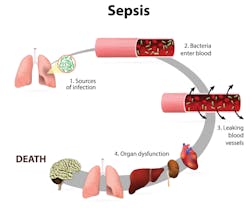

What is the clinical definition of sepsis? There is not universal agreement among experts. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines sepsis as the body’s “overwhelming and life-threatening response to an infection, which can lead to tissue damage, organ failure, and death.”1 The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3), published in February 2016 by an international panel of physicians, defined sepsis as “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.”2 The Sepsis-3 panel of 19 physician experts advocated that prior definitions overemphasized inflammation, and the term “severe sepsis” was overused and redundant.3

However it is defined, sepsis is prevalent and life-threatening. A 2014 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association estimated that it affects more than one million U.S. patients annually, and more than a quarter of those patients will die.4

According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), one in 23 hospitalized patients had septicemia in 2009, and 4,600 new patients were treated daily for the condition. Additionally, AHRQ reported that the mortality rate for sepsis is more than eight times higher than the mortality rates for patients hospitalized for other conditions.5

“Patients with co-morbid conditions or pre-existing illnesses are at even higher risk from a septic episode,” says Janis Atkinson, MD, Laboratory Medical Director, Presence Saint Francis Hospital in Evanston, Illinois. “A septic patient can lose blood pressure and tissue perfusion quickly, a situation that may be impossible to reverse.“

Sepsis is also expensive. The AHRQ reports that U.S. septicemia hospitalization costs in 2009 were in excess of $15.4 billion.6 In addition to its overwhelming human costs, sepsis drains a healthcare system that is in a time of transition and also financial strain.

Laboratory alerts for infection

Hematological parameters may alert practitioners to the presence of an underlying infection. Routine laboratory parameters include WBCs (white blood cell counts), ANC (absolute neutrophil count), and IG (immature granulocytes). Immature granulocytes are precursors to neutrophils, the body’s first responders to an infection. A neutrophil develops in the bone marrow during six stages of cellular maturation. The presence of immature neutrophils in the bloodstream is therefore an indication that the body is responding to inflammation, infection, or another stimulus to the bone marrow. This is often referred to as “left shift,” indicating a variety of conditions that must be more closely evaluated by the clinician. One possible cause of left shift is infection, especially a bacterial infection. Trauma, muscle injury, and a variety of other clinical conditions also may trigger left shift.

Other causes of left shift can include severe inflammatory disease, myelodysplastic syndromes, myeloproliferative disease, chronic myeloid leukemia, myelofibrosis, metastatic bone marrow malignancy, and acute organ transplant rejection. Because many of these conditions may co-exist with early stages of an infection or may have no relationship at all with an infection, identification of sepsis in its early stages is difficult. Staff education and screening tools can promote sepsis awareness and keep sepsis as a top-of-mind concern when evaluating patients.

Early identification and the lab’s role

Researchers and assay manufacturers are working to find better pathways to confirm a diagnosis of sepsis.

Alison Woodworth, PhD, DABCC, Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology, director of esoteric chemistry, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, has been working to identify biomarkers for detecting sepsis, and her research has shown promise.

“The newest research attempts to identify biomarkers that will differentiate sepsis from other causes of systemic inflammation,” says Woodworth. “Biomarkers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin alone are not able to accurately identify those patients with infectious inflammation, sepsis. We have also looked at various hematologic factors and other biomarkers, including immature granulocytes, ANC, WBC, procalcitonin, and CRP. Alone their utility is limited, but when combined their ability to diagnose the early onset of sepsis is significantly improved.”

In 2002, the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine collaborated to create the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC), a collaborative effort that now includes more than 30 clinical organizations worldwide.

In patients identified as experiencing severe sepsis, the SSC care bundle focuses on completing the following within three critical hours:

- measuring lactate levels

- obtaining blood cultures before administration of antibiotics

- administering broad spectrum antibiotics

- administering crystalloid for hypotension or lactate.

“I view the three-hour guideline as the longest acceptable response time,” says Jessica Colón-Franco, PhD, DABCC, Assistant Professor of Pathology, Medical College of Wisconsin, director of clinical chemistry and point-of-care, Wisconsin Diagnostic Laboratories and Froedtert Hospital. “Intervention as early as possible is preferable because early detection is so closely linked to better outcomes.”

“Lactate levels are considered a ‘super-stat’ in our hospital, and we monitor our turnaround times as part of our quality program,” says Atkinson. “We can perform them in the emergency room as a bedside test with results in minutes, or rapidly in the main laboratory to ensure that we meet the turnaround time guidelines. A high lactate level alerts the clinicians that the patient is in danger and prompts immediate intervention, which can be life-saving.”

In an effort to reduce nationwide sepsis mortality rates, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented new quality reporting measures (known as “SEP-1”) in October 2015. The policies mandate the use of SSC bundles and timeframes by all U.S. hospitals, reinforcing the importance of laboratory tests in the detection of sepsis.

“Sepsis diagnosis and treatment is a combined team effort of many specialties—laboratory medicine, infectious diseases, pharmacy, nursing, and physicians—coordinated to treat the patient as quickly as possible,” says Colón-Franco. “It is imperative to rule sepsis in and begin treatment, but it is also very important to rule sepsis out to avoid unnecessary use of antibiotics.”

Conclusion

The pathobiology of sepsis is complex, and detection can be difficult. New protocols and quality measures are standardizing sepsis care; however, early identification remains challenging for clinicians. The use of biomarkers and other laboratory tests, though far from perfect, can aid in early detection. The patient care goal is early detection supported by rapid response laboratory confirmation and immediate treatment, in order to achieve better patient care.

REFERENCES

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sepsis. http://www.cdc.gov/sepsis/.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Division of Healthcare Quality and Promotion. Sepsis questions and answers. http://www.cdc.gov/sepsis/basic/qa.html

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour C, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810.

- Liu V, Escobar GJ, Greene JD, et al. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts. JAMA. 2014;312(1):90-92.

- AHRQ, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Statistical Brief #122, Septicemia in U.S. Hospitals, 2009; October 2011.

- Elixhauser, A. (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality), Friedman, B. (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality), Stranges, E. (Thomson Reuters). Septicemia in U.S. hospitals, 2009. HCUP Statistical Brief #122. October 2011. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb122.pdf.

Anita Weissman, BS, MA, is a communications strategy consultant to healthcare, biotechnology, and medical device companies. As a communications consultant to the Community Oncology Alliance, Ms. Weissman played a key role in formulating national cancer care policy and regulatory action, including Congressional testimony and drafting legislation.

Sepsis diagnostics

What tests are used to diagnose sepsis? The Mayo Clinic lists the following tests to identify the underlying infection; which of them are utilized will depend to some degree on symptoms:

• Blood tests, for:

º Evidence of infection

º Clotting problems

º Abnormal liver or kidney function

º Impaired oxygen availability

º Electrolyte imbalances

• Urine (if the clinician suspects a urinary tract infection, to identify bacterial infection)

• Wound secretions (if a wound appears infected, to pinpoint the best antibiotic to use in treatment)

• Respiratory secretions (if the patient is coughing up mucus, to determine the pathogen responsible for causing the infection).

When the infection site is not obvious, imaging scans are used. These can include X-ray, computerized tomography (CT), ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).