For years, physicians and researchers have been working together using innovative technologies and cutting edge diagnostic tools to conceptualize personalized medicine—an approach that factors in patients’ genetic profiles to aid in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of a disease. The completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003, coupled with technological advances in clinical laboratory diagnostics—namely, laboratory developed tests (LDTs)—have further developed the practice of personalized medicine. While advances in patient care have been out in the forefront, federal regulations intended to monitor clinical laboratory tests, including LDTs, for safety and efficacy have lagged, leaving federal agencies and industry stakeholders enmeshed in an enormous debate.

To date, LDTs are dually regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) under The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA ‘88). The two agencies have distinct roles in regulating clinical laboratories and in vitro diagnostic (IVD) test systems. (An LDT is a type of IVD.) However, the increase in the use of LDTs as a diagnostic tool has revealed a gap in regulations that has resulted in a collaboration between federal agencies to determine the best mode of regulating diagnostic tests used to drive personalized medicine.

Industry stakeholders have energetically responded to the “Framework for Regulatory Oversight of Laboratory Developed Tests (LDTs)” draft guidance document that was released by the FDA in October 2014—both for and against. Proponents of more stringent LDT regulations are pleased that the agency has moved to close loopholes in LDT regulation that could potentially be harmful to patients’ health. Conversely, those in opposition to the guidance document have responded with alternative approaches that could be less prescriptive than the proposed mandates, including granting CLIA complete authority over LDTs.

All interested parties agree that a change in how LDTs will be monitored and by what federal agency is on the horizon. Accepting the change in regulations will require an in-depth understanding of the history of LDTs as well as the proposed (draft) regulations. More important, to benefit patient care, it is imperative that all stakeholders (federal agencies, diagnostic industry leaders, and clinical lab leaders) develop strategies for managing the modified LDT regulations while continuing the advancement of personalized medicine and bringing new technologies into the lab.

LDT regulations: identifying the gap

Under the Medical Device Amendments (MDA) of 1976, the FDA began regulating medical devices (including IVDs) according to a risk-based class system that requires device manufacturers to obtain pre-market clearance and approval prior to commercialization, thus providing some assurances of the safety and efficacy of these devices.1 While LDTs are considered to be a type of IVD, historically the FDA has opted to not impose the same regulatory oversight to LDTs as it does commercially available IVDs, leaving most LDTs to the regulatory arm of the CLIA ’88 amendments, administered by the CMS. The two agencies have distinct regulatory roles; the FDA’s oversight of IVDs is far more comprehensive and entails a review of both analytical and clinical validity of a test system, as well as additional post-marketing reporting and processes. CLIA regulations are more suited to ensure the quality of the testing process.2,3

The safety and efficacy of high complexity LDTs have been under scrutiny for more than twenty years. One of the earlier reports citing inadequacy in LDT regulations, the Genetic Testing Report, was published in 1997.4 The National Institutes of Health-Department of Energy (NIH-DOE) Task Force on Genetic Testing reported a number of laboratory quality-related issues associated with some genetics testing facilities that offer LDTs, including the lack of available proficiency testing, the failure of the testing facility to participate in inter-laboratory comparison programs, and the use of diagnostic tests that lack complete analytical and clinical performance characteristics. The report also concluded that the associated laboratory quality issues were in part due to vague and/or unenforced federal IVD (LDT) regulations. Since the release of the Genetic Testing Report, public interest groups have distributed many reports on the increase in the number of available LDTs and the lack of LDT regulation that could adversely impact patient care by producing erroneous results that lead to misdiagnosis and subsequent inappropriate or ineffective treatment.4,5

IVD issues: the regulatory response

The rapid growth and utility of LDTs is constantly evolving; simple LDTs have become high-complexity diagnostic tools that often require the use of advanced molecular technology and bioinformatics to interpret test results. Meanwhile, medical device regulations have subtly morphed. Over the last several years, federal agencies and associated industry stakeholders have tried to respond to the increasing trend in IVD platforms with various recommendations and draft guidance.

Nearly a quarter of a century after the inception of the medical device regulations, it became apparent to Congress and federal regulators that LDTs should be monitored more closely and that the current practice of the FDA’s nominal oversight of LDTs may not be the best practice.6 Since this realization, federal agencies have developed a task force charged with drafting new guidelines that will essentially apply more stringent requirements on the medical device industry, particularly in regard to LDT regulation. In October 2014, the IVD industry was awakened when the FDA released the long awaited draft guidance. In doing so, the FDA has provided a long-term risk-based plan (Figure 1) for closing the gap in the IVD regulations that has previously allowed LDTs to be available for clinical use prior to being adequately reviewed.7,8

As noted above, industry stakeholders on both sides of the issue have responded to the FDA’s proposed draft guidance. Both proponents and opponents of the modified regulations have raised legitimate issues that merit the FDA’s consideration prior to the issuance of the final guidance.

IVD regulations: a glance at the future

To date there may be as many as 100,000 LDTs being used as clinical diagnostic tools.9 The momentum in LDT development is likely to slow as the FDA begins to enforce IVD regulations. In advance of the proposed mandates, industry leaders fear that the FDA’s move to enforce IVD regulations, requiring some developers to acquire pre-market review and approval as well as become Quality System Regulation (QSR)-compliant, will halt innovation that has emerged as a trend in personalized care. The IVD industry must heed the FDA’s concerns about the safety and efficacy of the use of LDTs in patient care. Significant advances in LDT technology have underscored the inadequacies in CLIA’s process-oriented regulations, which are not fully equipped to provide regulatory oversight to LDTs that are not FDA-approved.

In the May 2015 issue of MLO, I published the article “Toward a culture shift in laboratory quality; application of the full ISO 15189 standard.” I discussed the lack of comprehensive clinical laboratory quality management systems (QMS) in U.S.-based medical testing laboratories. At that time, the focus was directed toward changing the culture of laboratory quality through ISO 15189 accreditation as a complimentary standard to CLIA regulations.10 The FDA’s move to enforce QSR compliance in LDT testing laboratories may serve as another route to reduce medical errors that diminish patient care outcomes. Balancing the multiple layers of regulations is likely to impose significant challenges for labs as they seek to maintain CLIA and FDA compliance, and in some cases various ISO standards.

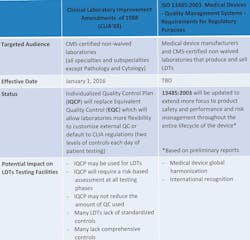

The FDA’s imposition of IVD regulation is not the only imminent regulatory change for laboratories to consider. LDT testing labs are also subject to changes in quality control (QC) requirements under CLIA regulations. Effective January 1, 2016, CMS non-waived laboratories, including LDTs, will have the option to develop Individualized Quality Control Plan (IQCP) or default to CLIA QC requirements. Another possibility that may specifically impact medical device developers is the anticipated changes to the international medical device standard ISO 13485, which is preliminarily staged to enhance various components of the standard (Table 1).11,12

Conclusion

Laboratory developed tests play an integral role in personalized medicine and have transformed medical practices from a one-size-fits-all model to highly personalized, target-specific care. Clinicians and patients are excited about the advances. However, federal agencies are highly concerned that the presence of unregulated LDTs, which are often clinically uncharacterized but are used for clinical diagnostics, poses threats to laboratory quality as well as patient safety and efficacy. In October 2014, when the FDA announced its plan to regulate all LDTs in the same manner in which it does traditional IVDs, the diagnostic industry broadly opposed the direction the FDA is taking. As we move into a new year, the industry eagerly awaits the FDA’s finalized guidelines and the beginning of the phase-in LDT regulation. The current uncertainty may soon give way to a better-defined protocol.

References

- The Medical Device Amendments of 1976 (MDA). 21 USC §360 et seq. (1976).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Overview of IVD regulation. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/IVDRegulatoryAssistance/ucm123682.htm. Accessed October 26, 2015.

- Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/index.html?redirect=/clia/. Accessed October 26, 2015.

- National Human Genome Research Institute. Promoting safe and effective genetic testing in the United States. http://www.genome.gov/10001733. Accessed October 26, 2015.

- Holtzman N. Promoting safe and effective genetic tests in the United States: work of the Task Force on Genetic Testing. Clin Chem. 1999;45(5):732-738.

- Sarata AK, Johnson JA, Congressional Research Services. Regulation of Clinical Tests: In Vitro Diagnostic (IVD) Devices, Laboratory Developed Tests (LDTs), and Genetic Tests. https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43438.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2015.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Draft guidance for industry, Food and Drug Administration staff, and clinical laboratories: framework for regulatory oversight of laboratory developed tests (LDTs). http://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/guidancedocuments/ucm416685.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2015.

- U.S. Food and Drug Adminstration.FDA notification and medical device reporting for laboratory developed tests (LDTs). http://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/guidancedocuments/ucm416684.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2015.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. (comment letter). https://www.aamc.org/download/423626/data/aamccommentsonfdaproposedguidanceonldts.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2015.

- Farmer T. Toward a culture shift in laboratory quality: application of the full ISO 15189 standard. MLO. 2015;47(5):38 https://www.mlo-online.com/toward-a-culture-shift-in-laboratory-quality-application-of-the-full-iso-15189-standard.php. Accessed May 26, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CLIA Individualized Quality Control Plan: an introduction, July 2013. https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/legislation/clia/downloads/cliabrochure11.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2015.

- ISO 13485 2015 v ISO 13485 2003. http://www.praxiom.com/iso-13485-new.htm. Accessed October 26, 2015.