Navigating through crisis in a pandemic event

The 1918 H1N1 pandemic illustrates one of the worst scenarios for preparedness, as it produced the greatest influenza mortality in recorded history. It is estimated that about 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population at the time became infected with the virus and at least 50 million died.1 Since that time, disease outbreaks, natural disasters and other mass casualty events have pushed healthcare systems to identify and refine emergency preparedness protocols.2

In 2009, the Institute of Medicine issued the “crisis standards of care” to define the level of health and medical care capable of being delivered during a catastrophic event. An event that would most likely stem from a pervasive (e.g., pandemic influenza) or catastrophic (e.g., earthquake, hurricane) disaster by which healthcare resources become overwhelmed.3 Today, the world is currently facing such an event due to SARS-Cov-2; the virus behind the COVID-19 pandemic.

Given the growing disease burden caused by SARS-CoV-2 and the ensuing COVID-19 infections across the globe, health officials are facing ethical dilemmas and difficult decisions governing the provision of care with limited resource supplies. In vitro diagnostic companies play a crucial role within the healthcare ecosystem, and as such, it is vital that we work to support the continuous improvement of our ability to better respond to pandemics and provide support to those on the front lines as they navigate through crisis.

Clinical laboratories are often the first line of defense in response as they perform diagnostic testing and oftentimes may be the first to identify the causes of illnesses in communities. It is thus important that laboratories update and maintain their pandemic preparedness protocols and training throughout the year.

Evolution of a novel pandemic

This is the third serious coronavirus outbreak in less than 20 years, following SARS in 2002-2003 and MERS in 2012.4 As SARS-CoV-2 appears to be transmitted person-to-person through respiratory droplets and close contact, a key component of risk mitigation is prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection in at-risk populations. Current evidence suggests these populations include older adults, those with serious chronic medical conditions, immunosuppressed patients, and those with prior or active cancer.5 Globally, as we continue to see younger people being affected, we should remain fully cognizant that the young and healthy are not free of risk of death.6

Additionally, health disparities and global health inequities represent some of the greatest barriers to pandemic preparedness.7 For example, in New York city, the Hispanic coronavirus victims comprised 34 percent for all COVID-19-related deaths as of April 2020, while making up only 29 percent of the city’s population. Similarly, In Chicago, African Americans constituted 71 percent of deaths, whilst making up 29 percent of the population.8

Poverty and health are connected in that minority communities may have generations of poverty and higher preexisting health conditions such as hypertension, diabetes and asthma that put them at greater risk during a pandemic. Crowding, another established risk factor which has been associated with Hispanic and Asian households, can also increase the likelihood of pathogen transmission.9

There is some reassurance that perhaps over 80 percent of symptomatic subjects will experience only mild flu-like symptoms. However, it is concerning that perhaps 15 percent of affected patients will become seriously ill and 5 percent will need critical care. Respiratory viruses are known to respond to seasonal variation, and we might expect that increasing temperatures in the summer could reduce the transmissibility of the novel coronavirus to some extent. As warmer weather may slow down the spread, it will continue to be prudent to interrupt community transmission via social distancing strategies.10 Furthermore, In conjunction with public health efforts, health systems can dramatically expand access to testing through commercial, hospital and public health laboratories.11,12

Standard testing for acute infection entails reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) amplification of reverse-transcribed viral RNA from respiratory specimens, most commonly nasopharyngeal swabs, but also oropharyngeal swabs, sputum, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.13

Serological testing will also be valuable for evaluating the extent of the pandemic. With the ability to assess a patient’s immune response to SARS-CoV-2, this testing modality may enable clinicians to clear hospital staff, emergency responders and others to get back to work with an indication that they have had prior exposure and therefore, may have some level of immunity to the disease. This test also could allow those without immunity to be identified and kept safe until the pandemic subsides.Building a strong foundation for preparedness

Preparing for a potential infectious disease pandemic from influenza or a novel coronavirus is an essential component of a business continuity plan, especially for businesses that provide critical healthcare and infrastructure services. Pandemics can not only interrupt an organization’s operations and compromise long-term viability of an enterprise, but also disrupt the provision of critical functions. Businesses that regularly test and update their pandemic plan can significantly reduce harmful impacts to the business, play a key role in protecting associates’ and customers’ health and safety, and limit the negative impact of a pandemic on the community and economy.14 It is important to lay a foundation for regularly training staff, especially those within the lab, about business continuity in the event of a pandemic.

In order to keep associates healthy, everyone must do their part. Hand hygiene with soap and water, washing for 20 seconds, or alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) are the most effective, simple and low-cost measures against COVID-19 cross-transmission. By denaturing proteins, alcohol inactivates enveloped viruses, including coronaviruses, and thus, ABHR formulations with at least 60 percent ethanol have been proven effective for hand hygiene.15 Soap contains fat-like substances known as amphiphiles, and the soap molecules “compete” with the lipids in the virus membrane. The chemical bonds holding the virus together are not very strong, so competition is enough to break the virus’s coat as well as any grease or dirt they may be clinging to.16

At this time, there are no vaccines available and there is little evidence on the effectiveness of potential therapeutic agents. In addition, there is presumably no pre-existing immunity in the population against the new coronavirus and everyone in the population is assumed to be susceptible.15 When a novel virus with pandemic potential emerges, nonpharmaceutical interventions, are often the most readily available interventions to help slow transmission of the virus in communities. Community mitigation is a set of actions that persons and communities can take to help slow the spread of respiratory virus infections. Community mitigation is especially important before a vaccine or drug becomes widely available.16

During this time, it is important to establish clear roles and responsibilities. This can be coordinated through the formation of a crisis management team. This team provides guidance, and support regarding priorities and direction for response and recovery from an enterprise perspective. Establishing clear roles and communication should take a multi-tiered organizational structure to maximize protection of life and minimize potential interruptions to business continuity. To ensure readiness, the importance of training and tabletop exercises cannot be understated and should be incorporated into overall disaster preparedness efforts.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has described four levels of mitigation strategies by level of community transmission: none to minimal, minimal to moderate, substantial and post-pandemic.18

None to minimal:

- Know where to find local information on COVID-19 and local trends of COVID-19 cases.

- Know the signs and symptoms of COVID-19 and what to do if staff become symptomatic at the worksite.

- Review, update, or develop workplace plans to include:

- Liberal leave and telework policies

- Consider 7-day leave policies for people with COVID-19 symptoms

- Consider alternate team approaches for work schedules

- Encourage employees to stay home and notify workplace administrators when sick (workplaces should provide non-punitive sick leave options to allow staff to stay home when ill).

- Encourage personal protective measures among staff (e.g., stay home when sick, handwashing, respiratory etiquette).

- Clean and disinfect frequently touched surfaces daily.

- Ensure hand hygiene supplies are readily available in building.

Minimal to Moderate:

- Encourage staff to telework (when feasible), particularly individuals at increased risk of severe illness.

- Implement social distancing measures:

- Increasing physical space between workers at the worksite

- Staggering work schedules

- Decreasing social contacts in the workplace (e.g., limit in-person meetings, meeting for lunch in a break room, etc.)

- Limit large work-related gatherings (e.g., staff meetings, after-work functions).

- Limit non-essential work travel

- Consider regular health check (e.g., temperature and respiratory symptom screening) of staff and visitors entering buildings (if feasible).

Substantial:

- Implement extended telework arrangements (when feasible).

- Ensure flexible leave policies for staff who need to stay home due to school/childcare dismissals.

- Cancel non-essential work travel.

- Cancel work-sponsored conferences, tradeshows, etc.

Post-pandemic:

- Guided by surveillance data, implement a phased approach to returning to work and full operations.

- Gradually ease physical distancing measures in a concerted and careful manner and continue to control SARS-CoV-2 transmission so we do not revert back.

- To ultimately move away from future reliance on physical distancing as our primary tool for controlling future spread, we need:

- Better data to identify areas of spread and the rate of exposure and immunity in the population.

- Improvements in state and local healthcare system capabilities, public-health infrastructure for early outbreak identification, case containment, and adequate medical supplies.

In conclusion

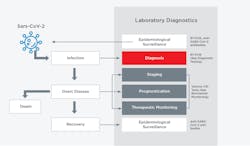

The rapid spread of COVID-19 across the world has exposed major gaps in the abilities of most countries to respond to a virulent new pathogen. Moving forward, as we work to control the COVID-19 pandemic and as we plan for future pandemics, a key lesson is that early availability of diagnostic testing is of great value for patient management and public health. Thus, the development, validation, scale-up in manufacture, and distribution of diagnostic tests should be a key priority in early preparation during an emerging infectious disease outbreak.

The examples of Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong in limiting the impact of the sudden acute respiratory syndrome, SARS-CoV-2, demonstrates that it is possible to mount an effective response to an outbreak via major investment in pandemic preparedness.19

Early in an outbreak, we need to understand and define the risk factors for infection, the role of asymptomatic or mild infection and the nature of ‘super-spreaders.’ We must improve response rates and estimates of death rates by age.20 This will help forward looking viral pandemic preparedness.

Last, businesses that regularly test and update their pandemic plan can significantly reduce harmful impacts to the business, play a key role in protecting associates’ and customers’ health and safety, and limit the negative impact of a pandemic on the community and economy. For healthcare organizations, regular training of staff for preparedness and readiness inclusive of revised workflows – should they be needed – is crucial, as these frontline healthcare workers are key to protecting and treatment of the population at large.

References:

- Belser, J.A. and T.M. Tumpey, The 1918 flu, 100 years later. Science, 2018. 359(6373): p. 255.

- Jester, B.J., et al., 100 Years of Medical Countermeasures and Pandemic Influenza Preparedness. Am J Public Health, 2018. 108(11): p. 1469-1472.

- Crisis standards of care: Guidance for establisning crisis standards of care for use in disaster situations ( IOM, 2009)

- Yang, Y., et al., The deadly coronaviruses: The 2003 SARS pandemic and the 2020 novel coronavirus epidemic in China. J Autoimmun, 2020: p. 102434.

- Liang, W., et al., Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol, 2020. 21(3): p. 335-337.

- Hennekens, C.H., et al., The Emerging Pandemic of Coronavirus: The Urgent Need for Public Health Leadership. Am J Med, 2020.

- Satcher, D., The impact of disparities in health on pandemic preparedness. J Health Care Poor Underserved, 2011. 22(3 Suppl): p. 36-7.

- Joe Barrett, C.J.a.E.R., Mayors Move to Address Racial Disparity in Covid-19 Deaths, in The Wall Street Journal. 2020.

- Blumenshine, P., et al., Pandemic influenza planning in the United States from a health disparities perspective. Emerg Infect Dis, 2008. 14(5): p. 709-15.

- Wang, J., et al., Preparedness is essential for malaria-endemic regions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet, 2020.

- Hick, J.L. and P.D. Biddinger, Novel Coronavirus and Old Lessons - Preparing the Health System for the Pandemic. N Engl J Med, 2020.

- Korr, K.S., On the Front Lines of Primary Care during the Coronavirus Pandemic Shifting from office visits to telephone triage, telemedicine. R I Med J (2013), 2020. 103(3): p. 9-10.

- Rosenthal, P.J., The Importance of Diagnostic Testing during a Viral Pandemic: Early Lessons from Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2020.

- Koonin, L.M., Novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak: Now is the time to refresh pandemic plans. J Bus Contin Emer Plan, 2020. 13(4): p. 1-15.

- Lotfinejad, N., A. Peters, and D. Pittet, Hand hygiene and the novel coronavirus pandemic: The role of healthcare workers. J Hosp Infect, 2020.

- Thordarson, P. The coronavirus is no match for plain, old soap — here’s the science behind it. 2020 [cited 2020 April 8th]; Available from: https://www.marketwatch.com/story/deadly-viruses-are-no-match-for-plain-old-soap-heres-the-science-behind-it-2020-03-08.

- Eurosurveillance Editorial, T., Updated rapid risk assessment from ECDC on the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: increased transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK. Euro Surveill, 2020. 25(10).

- Qualls, N., et al., Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza - United States, 2017. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2017. 66(1): p. 1-34.

- Sheridan, C., “Fast, portable tests come online to curb coronavirus pandemic.” Nat Biotechnol, 2020.

- Watts, C.H., P. Vallance, and C.J.M. Whitty, Coronavirus: global solutions to prevent a pandemic. Nature, 2020. 578(7795): p. 363.

About the Author

Shamiram Feinglass MD, MPH

is the Vice President, Global Government and Medical Affairs at Beckman Coulter. In this position, she leads Global Medical, Government, Reimbursement, and Clinical Affairs for Life Sciences and Diagnostics and drives talent diversity in every environment in which she works or leads. Feinglass was formerly the Vice President for Global Medical and Regulatory Affairs at Zimmer, Inc.

Joseph Chiweshe, MD, MPH

is Senior Manager; IDN & Evidence Generation for Beckman Coulter’s North America Commercial Operations (NACO) Strategy & Partnership marketing team. Dr. Chiweshe was formerly a Global Medical Innovations Manager for Beckman Coulter’s Strategy and Innovation team where he was responsible for leading long-term transformational opportunities.