An Associate Professor in the Ronald O. Perelman Department of Dermatology and Department of Pathology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Amanda W. Lund, PhD, studies the lymphatic vasculature, which plays an important role in clearing body tissues of the excess fluid and cells that build up within them, according to a news release.

On the return trip into the blood, immune cells in the lymph nodes survey the contents to identify threats and activate an immune response, if needed.

She examines the relationship of the lymphatic vasculature to cancer to better understand this system and its role in cancer metastasis, and more.

What is the lymphatic vasculature, and why is it important in cancer?

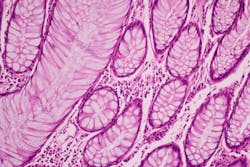

Lymphatic vessels are a crucial part of our circulation. Unlike blood vessels, which move nutrients and oxygen through all of our tissues, lymphatic vessels are a one-way route out of tissue, moving lymph through lymph nodes and ultimately back into the blood. The reason they are important is they play a critical role in maintaining fluid homeostasis (balance), are the critical routes for trafficking of immune cells, and play an important role in lipid transport. Their normal function is required for tissue homeostasis and health, and we think their dysfunction in the context of cancer has two main important impacts.

First, as they expand and respond to the developing malignancy, lymphatic vessels can provide routes for tumor cells to exit and metastasize to lymph nodes. Researchers know that, for many solid tumors, the presence of tumor cells in lymph nodes is an early event and poor prognostic for patients. Studying these vessels in the context of cancer, researchers have also learned that, as the critical route for leukocyte (white blood cell) migration out of tissues, they are required for immune surveillance against tumors. They allow the host to see a developing malignancy and initiate antitumor immune responses. But then, through mechanisms that researchers in the field don’t fully understand, they also can contribute to the tumor’s ability to evade the immune system.

Lund’s lab is interested in understanding what the signals are that move through this system to regulate these different immunological processes and how the evolution of that immune response against the tumor can also contribute to metastasis and eventually poor outcomes for people with cancer.

“One of the projects that I am very excited about, which we have been working on for several years, is understanding the dynamics of T-cell movement out of tumors,” Lund said. “The field of cancer immunology has appreciated that the CD8 T cell—the killer T cell—is a vital component of response to immunotherapy. These are the cells that are protecting patients on checkpoint inhibitor therapy. The more we understand how killer T cells work and how we get them into tumors, the better. Yet one aspect that has gone unappreciated is the dynamics of not only what gets T cells into the tumor microenvironment, where they can exert their killing function, but whether or not they stay in that environment, or if instead they recirculate out. When they recirculate out, they do that via the lymphatic vasculature.”

“We have been investigating those “stay and leave” signals and trying to understand what the mechanisms are that tell a T cell that found its target to stay versus maybe move on and continue to survey other tissues. We think that tumors put up a lot of barriers to T-cell retention, and the lymphatic endothelium in the tumor itself seems to be promoting the exit of a broad, diverse, functional set of T cells. We have been exploring these mechanisms in order to think about whether or not we could block the exit of T cells from the tumor in order to boost retention, and, ultimately, response to immunotherapy. That has led to a lot of additional questions—which we are exploring—regarding the role of lymphatic recirculation and how the lymphatic endothelium itself informs that process. That has been an exciting area for us.”

“We have focused on melanoma, but in addition to the cancer work that we do, we also conduct a lot of basic immunology research in the skin. Comparing and contrasting what we find within the same tissue has been informative for us. We are, however, really excited by ongoing conversations with researchers who study other tumor types. We think that the kinds of questions we are asking are relevant across tissues. We are excited to continue to build these collaborations here at Perlmutter Cancer Center and think broadly about lymph node biology and lymphatic transport in cancer,” Lund said.

“We are thinking of benefits in two ways. First, I think that the work we are doing to understand the interplay between the host immune response and the lymphatic vasculature might lead us to novel combination therapies, ways to target how the host “sees” the tumor in conjunction with immune checkpoint blockade, for example. Second, we are also thinking about the trafficking behavior of T cells as potential engineering strategies for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. Again, this probably will not be specific to melanoma.”

“Fundamentally, lymphatic transport is engaged very early in tumor progression. And a lot of the biology that we are looking at is operating at the earliest stages in the patient,” explains Lund. “We have become more successful treating metastatic disease. I think we have the opportunity to think about these early mechanisms and how we might intercept disease progression to keep people with cancer from reaching an end-stage metastatic state. There are a lot of challenges to doing that; for example, identifying the patients that are actually at high risk for disease progression and determining whether the mechanism we are targeting is operative in that subset of patients. However, that is the direction we are heading: How do we identify patients early, and how do we direct care in those patients with high risk to interrupt disease progression?”