In a new article published in Clinical Cancer Research, Moffitt Cancer Center researchers reveal how different therapies impact the surrounding immune environment of metastatic melanoma tumors according to location and identify a rare population of immune cells that is associated with improved overall survival, according to a news release from the organization.

Different types of cancer tend to spread to specific sites throughout the body. Common sites of melanoma metastases are the brain, lungs, liver, and bones. Approximately 40% to 60% of melanoma patients develop metastatic disease within the central nervous system, while 5% of patients develop metastatic disease within the area of the leptomeninges, the two innermost layers of tissue that cover the brain and spinal cord, and the cerebrospinal fluid. Patients with leptomeningeal melanoma metastases have a very poor prognosis, with a mean survival of only eight to 10 weeks. Despite this poor prognosis, a handful of patients with leptomeningeal melanoma metastases show increased survival, but the reasons for this are unclear.

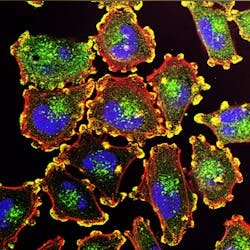

Moffitt researchers want to improve their understanding of why some metastatic melanoma patients respond better than others and determine which cellular factors contribute to these improved responses across different metastatic sites. They analyzed the RNA expression patterns of individual melanoma and immune cells from 26 patients with metastatic melanoma of the skin, brain and leptomeninges/cerebrospinal fluid, and used this information to determine the specific immune cell types that were present within each sample.

They discovered that the types of cells within the tumor microenvironment varied according to the site of metastasis. Leptomeningeal melanoma metastases were characterized by an immune-suppressed environment, with a high percentage of dysfunctional CD4 and CD8 T cells that are incapable of mounting an immune response, and low levels of B cells. Alternatively, samples from brain and skin metastases were much more alike in their immune environment, with an enrichment for activated CD4 T cells.

The researchers analyzed how the immune environment of metastatic sites is modulated by different regimens and what types of immune cells are associated with better responses. They compared data from a patient with leptomeningeal melanoma metastases who had a good response to treatment and survived for more than 38 months, to data from five patients who had poor responses to treatment. They found that the long-term survivor had an immune environment that was more like patients without leptomeningeal disease, whereas poor responding patients had immune environments characterized by immunosuppressive myeloid cells and exhausted lymphocytes, a recipe for diminished antitumor responses. Samples derived after treatment revealed that the long-term survivor had cells characteristic of an active immune response, and patients who responded poorly to therapy did not have these cells present.

A further analysis of dendritic cells that play an important role in therapy response showed that a subpopulation, called DC3s, were associated with improved overall survival and the presence of an active T cell immune response, regardless of the site of metastasis or treatment history. The researchers confirmed the importance of DC3s to patient outcomes through preclinical studies in mouse models.