This year, the American Cancer Society estimates that 13,240 women will be diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer and approximately 4,170 women will die from cervical cancer.1 While those numbers are alarming, consider that cervical cancer was once one of the most common causes of death for American women, and the latest estimates represent a significant decrease from a time when cervical cancer deaths were at their peak.

As a long-time practicing OB-GYN, I, like many of my colleagues, have diagnosed, managed, or co-managed a number of patients with cervical cancer. Such experiences emphasize the importance of rigorous and timely screening evaluations for a disease which is, for the most part, treatable if detected in its early stages. And although the population trend line for cervical cancer deaths has a downward slope, such data mean very little to the individual patient whose life is at stake. It is therefore important to remember that, while current age-based co-testing guidelines for cervical cancer screening, which are supported by The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP), are shifting, we as physicians must always provide screening methods that allow us to most effectively counsel our patients about their health and well-being.

HPV infection rates and cervical cancer

The majority of cervical cancer cases are caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), a group of more than 200 related viruses. These types are grouped by low risk and high risk for causing cancer. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that 45 percent of Americans ages 18 to 59 carry some form of HPV, and about 20 percent of women with HPV have been exposed to a HR-HPV (high-risk HPV).2 Low-risk HPVs do not cause cancer but can cause skin warts (technically known as condylomata acuminata). In addition to low-risk HPVs, about a dozen HR-HPVs have also been identified. Two of these, HPV types 16 and 18, are responsible for most HPV-caused cancers.3

Most high-risk HPV infections occur without any symptoms, go away within one to two years, and do not cause cancer. Some HPV infections, however, can persist for many years. Persistent infections with high-risk HPV types can lead to cellular changes that, if untreated, may progress to cancer.

Anyone who has been sexually active (genital or oral) may have been infected with HPV, because HPV is easily passed between partners through sexual contact. While HPV infections are more likely to occur in those who have many sex partners or have sex with someone who has had many partners, because the infection is so common, a person who has had only one partner may still contract HPV. Although cases of HPV are not formally reported in the United States, available data from the CDC indicate that at least 75 percent of the reproductive-age population has been exposed to sexually-transmitted HPV.

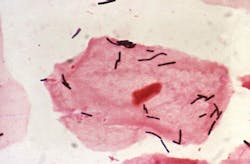

Cervical cancer remains one of the most preventable types of cancer with appropriate guideline-based screening. Screening typically employs cytology (the Papanicolaou or Pap test), molecular testing for HPV, or a combination of both tests (co-testing).

Cytology screening helps clinicians identify precancerous changes in the cervix called cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or cervical dysplasia. Almost all of the declines in deaths from cervical cancer in the United States since the 1950s are due to cytology screening by the Pap test (and the expertise of the cytotechs and other lab professionals who interpret the findings).4

Because cervical cancer is typically caused by HPV infection, HPV testing plays an important role in cervical cancer screening. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved tests that can detect 14 high-risk types of HPV (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68) and report results as positive when any of these types is detected. Some tests may reflex to genotyping for HR-HPV, namely HPV 16, 18, and 45. These HPV screening tests aid in managing a woman’s cervical health and lowering risk of cervical cancer incidence and death.

Age and cervical screening

While HPV infection is very common in sexually active women, younger women tend to have infections that are more transient and resolve on their own. Once a woman turns 30, there is a greater risk that her infection is a high-risk type that will not resolve on its own.

Professional associations such as ASCCP and ACOG recommend that women 21 to 29 years of age receive Pap testing alone every three years, with a reflex to a HR-HPV test if the Pap result is ASC-US (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance). If the woman has a Pap ASC-US result, and the reflex to HR-HPV is detected (“positive”), the recommendation is to proceed to a more thorough investigation of the cervix by using colposcopy.

Between ages 30 and 65 years, women should either receive a Pap test every three years or a Pap test plus HPV test (co-test) every five years, according to current guidelines. Because of the high negative predictive value of the two tests, women who test negative for both HPV and Pap test should not be screened again for five years.5

When genotyping is recommended

Importantly, ASCCP and ACOG do not recommend genotyping, such as for types 16 and 18, for women with a Pap ASC-US result and a positive HR-HPV. This is largely because knowing this result may not alter patient management. It is recommended that these women go straight to colposcopy. Consider that while 50 percent of CIN2 and more severe lesions are associated with genotypes 16 and 18, the other 50 percent are not. About 13 percent of women with an ASC-US positive and HR-HPV negative result may progress to CIN2 within two years.6

However, there are cases where HR-HPV genotyping is appropriate. In women ages 30 to 65, where the ASCCP guidelines recommend co-testing with Pap and HPV together as one option, genotyping is recommended when Pap is normal (NILM) and the HR-HPV result is positive. In this case, genotyping information may aid the clinician in determining if a woman should be referred for immediate colposcopy versus follow-up with cytology and HR-HPV testing in 12 months.7

HPV as a primary screening method

HPV causes the vast majority of cervical cancers, so it may be tempting to conclude HPV screening could be a reliable surrogate for cytology screening. In fact, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently issued draft guidelines suggesting that the average 30-to-65-year-old woman could eliminate the Pap test in favor of HPV testing as a standalone screening method.8 (The USPSTF is expected to issue final guidelines in 2018.)

These draft guidelines are not without controversy, and have been challenged by several professional groups, including the Cytopathology Education and Technology Consortium, which includes the College of American Pathologists, the American Society for Cytotechnology, the American Society of Cytopathology, and the American Society for Clinical Pathology. ACOG has also responded to the USPSTF draft by stating that co-testing for 30-to-65 year olds should remain in the guidelines. Research points to the fact that reducing or eliminating cytology for cervical screening from women ages 30 to 65 may miss some cancers and pre-cancers, potentially undoing decades of progress in reducing incidence rates of cervical cancer. HPV-positive tests without a cytology result may also prompt unnecessary confirmatory procedures, namely colposcopy and biopsy, which can be challenging, risky, and invasive.

Special considerations: pregnancy and vaccines

When selecting appropriate tests, physicians understand that women in their 30s may be thinking about pregnancy. While a colposcopy itself does not interfere with fertility, confirming a patient’s cervical health through additional and potentially unnecessary appointments and procedures may delay a woman’s reproductive timeline. Because HR-HPVs may resolve on their own, these procedures are likely to cause stress without providing actionable insights.

In addition, women who are now in their 30s were some of the first to receive the HPV vaccine when it was approved for the prevention of cervical cancer and other HPV-related diseases in 2006. Current guidelines recommend that people who have been vaccinated should continue to be tested like non-vaccinated women as the vaccine protects against some, but not all types of HPV.

A comprehensive approach

Screening for cervical disease and for cancer is an important part of a woman’s overall health and wellness. As women reach their 30s they face a new set of challenges due to changes in biology that may impact their cervical health and require an age-based approach to care. It is also an opportune time for women to build a relationship with their OB-GYN as they outline the intervals for a cervical health screening program. Physicians should employ a comprehensive approach to cervical screening that utilizes both cytology and HPV testing to provide the most actionable insights, while minimizing the potential for over-screening that could lead to false positives, undue patient anxiety, and unnecessary procedures.

REFERENCES

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Cervical Cancer.

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. - McQuillan G, Kruszon-Moran D, Markowitz LD, Unger ER, Paulose-Ram R. Prevalence of HPV in adults aged 18–69: United States, 2011–2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCHS Data Brief No. 280. April 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db280.pdf.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/hpv.html.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Manual for the surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/surv-manual/chpt05-hpv.html.

- United States Preventative Services Task Force. Cervical cancer: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cervical-cancer-screening.

- Cox JT, Schiffman M, Solomon D. Prospective follow-up suggests similar risk of subsequent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 among women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1 or negative colposcopy and directed biopsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003:188(6):1406-12.

- American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP). 2012 Updated Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors. http://www.asccp.org/Assets/405b4550-593f-40a7-ae25-0c783de95b0d/635912114192570000/asccp-updated-guidelines-3-21-13-pdf.

- United States Preventative Services Task Force. Cervical cancer screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFileByID/3288.

Damian P. Alagia, III, MD, MS, MBA, serves as Medical Director of Woman’s Health for Quest Diagnostics.