A decade lost to the drug crisis: Toxicology testing magnifies America’s misuse

Ten years ago, drug overdoses claimed nearly 42,000 lives annually in the United States.1 By the end of 2021, that number climbed to nearly 108,000.2 Today, the drug crisis shows no signs of abating, and remains largely fueled by increased access to illicit drugs as well as barriers to healthcare access exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

For the last decade, Quest Diagnostics, through its Health Trends program, has examined insights gleaned from results of our large volume of clinical drug tests, with a goal of empowering better patient care, population health management and informing public health policy. Our annual scientific report on prescription drug misuse sadly shows that drug misuse — including potentially dangerous drug mixing — remains prevalent, with patients of all ages and both sexes at risk.3

The findings of this year’s report, based on a cohort of 20 million deidentified clinical drug tests, reveal the persistence of the prescription and illicit drug crisis. While illicit fentanyl drives most overdose deaths, the misuse of opioids, benzodiazepines, amphetamines and other controlled substances prescribed by a physician is a pressing medical and social concern. In fact, nearly 1 in 4 opioid overdose deaths in 2020 were due to prescription opioids, a 16% increase from 2019.2

Data from testing shows a decline of misuse, but an increase in dangerous drug mixing

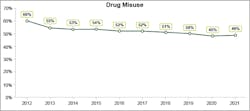

Throughout the last decade, though recent years have seen a decline in overall misuse, the rate of patients tested by Quest Diagnostics with signs of drug misuse has remained exceedingly high (Figure 1). As of 2021, roughly 1 in 2 patients (49%) generated test results suggesting misuse, i.e., either a) additional drugs were found with the patient’s prescribed medication(s); b) different drugs were found than the prescribed medication; or c) no drugs were found (indicating possible diversion).6

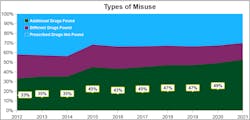

These data are even more concerning given some test results suggested an increase in the mixing of synthetic fentanyl with other drugs, often without the user’s knowledge.7 Fentanyl is a highly potent synthetic opioid that can depress respiration when combined with other drugs, leading to overdose and death. In 2020, Quest reported a surge in drug combining involving nonprescribed fentanyl with amphetamines, opiates (which also includes opioids), and other drugs during the early months of the pandemic (Figure 2).8

While substance use disorder (SUD) creates substantial costs for hospitals and payers ($13.2 billion annually), few hospital patients receive SUD treatment services.9 But access to these services may abate the need for further treatment down the line, ultimately leading to savings in the overall cost of care. In fact, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, there is “strong evidence that treatment and management of substance use disorders provides substantial cost savings.” For instance, methadone treatment has been found to generate $4 to $5 in returns on healthcare expenditures for every $1 invested.10 By an estimate outlined in 2017, the economic costs of the U.S. opioid epidemic, due to healthcare expenses, criminal justice, lost productivity and reduced quality of life, top $1 trillion annually.11

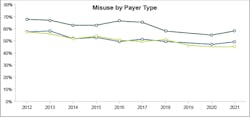

Though the drug misuse crisis touches individuals at all walks of life, Quest’s data shows patients covered by Medicaid consistently had higher rates of misuse than patients with commercial insurance or enrolled in Medicare (Figure 3). Other research suggests that individuals in Medicaid are comparatively more likely to have risk factors for substance use disorders, such as mental illness and economic disadvantage.2 Given this data, broadly testing all patients, regardless of individual demographics, may help to reduce bias and diminish stigma around drug monitoring. In fact, in its recently released guidelines, the CDC recommends that “clinicians, practices, and health systems should aim to minimize bias in testing and should not apply this recommendation differentially on the basis of assumptions about patients.”4

Finally, there has been significant discussion over the years about the need to minimize the use of definitive testing to limit costs, mostly due to a few bad actors in the industry seeking to improperly utilize testing for financial gain. While reducing costs of toxicology testing is a worthwhile goal, and not all patients will require a definitive test, clinical drug testing fits in a larger landscape of patient care, from treatment for substance use disorders to emergency department visits for overdose — some of which toxicology testing may help to avert, as mentioned above.

Though presumptive point-of-care tests are an important tool for clinicians, they are often less sensitive and can miss drugs that definitive lab tests will detect. Recent data shows point-of-care presumptive urine tests may miss about 74% of specimens with fentanyl, as determined by sensitive definitive laboratory tests. These same point-of-care tests were also shown to have missed large percentages of other drugs, including marijuana, amphetamine, methamphetamine, oxycodone, and cocaine.12 Yet, presumptive tests still have an important role to play, such as for low-risk patients.

Conclusion: Toxicology screening remains an important tool in prevention

It is difficult not to feel hopeless when examining the results of a decade of drug monitoring and the conclusion drawn by the data: that the crisis of prescription and illicit drug use is unlikely to end soon. According to the Quest data, about half of all patients tested showed signs of drug misuse in 2021, roughly the same proportion as ten years ago. On top of this, potentially dangerous drug combining actually rose during the same period.

Much of today’s national discourse on the drug crisis focuses on reducing harm in individuals who have already developed a dependency and are at heightened risk of drug combining and overdose, particularly from illicit fentanyl. Policies to encourage early detection and reduce harm in individuals with an established dependency are urgently needed. Yet, in some ways, these measures address the problem too late, after a substance use disorder has already led to serious harm or tragedy.

For many other conditions, such as cancer and heart disease, a preventative care model is widely accepted. Yet, when it comes to preventing drug misuse and substance use disorder, treatment often begins in the back of an ambulance, illustrating just how vital greater attention on the earliest stages of risk is. Data shows a majority of physicians agree: clinical drug testing is the only objective source of insight into a patient’s drug use behaviors. These tests act as screenings to provide unbiased insight into potential risk, inform clinical decisions, and preempt the worst outcomes from drug misuse.

But screening for drug misuse is only one part of the solution. Policies must also address the underlying dynamics that drive some individuals to misuse, like mental health conditions, including anxiety and depression, or social disparities of health, including poverty. Lack of access to healthcare, including mental healthcare, further limits opportunities for intervention.

If the nation wants to mitigate the drug misuse crisis, physicians and policy makers should implement measures to reduce stigma and prevent bias, including with respect to lab testing. Standardization of care may be one way to help reduce physician bias in patient monitoring, clinical drug testing, and treatment decisions — and hopefully, it won’t take another ten years of data to convince the country to act.

References

- Multiple cause of death data on CDC WONDER. Cdc.gov. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html.

- Saunders H, Rudowitz R. Demographics and health insurance coverage of nonelderly adults with mental illness and substance use disorders in 2020. KFF. Published June 6, 2022. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/demographics-and-health-insurance-coverage-of-nonelderly-adults-with-mental-illness-and-substance-use-disorders-in-2020/.

- Drug Misuse in America, 2021: Physician Perspectives and Diagnostic Insights on the Drug Crisis and COVID-19. Quest Diagnostics. Published November 2021. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://filecache.mediaroom.com/mr5mr_questdiagnostics/203277/PRUS.COCM.CL.006259_001_Quest_Hazel_PDMSurveyReport_W27.pdf.

- Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain — United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep 2022;71(No. RR-3):1–95. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1.

- Langman LJ, Jannetto PJ. Using Clinical Laboratory Tests to Monitor Drug Therapy in Pain Management Patients at 7. AACC Academy, Laboratory Practice Guidelines. American Association for Clinical Chemistry; 2018.

- Quest Diagnostics internal drug monitoring data.

- NIDA. Fentanyl DrugFacts. National Institute on Drug Abuse website. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/fentanyl. June 1, 2021 Accessed January 3, 2023.

- Niles JK, Gudin J, Radcliff J, Kaufman HW. The Opioid Epidemic Within the COVID-19 Pandemic: Drug Testing in 2020. Popul Health Manag. 2021;24(S1):S43-S51. doi:10.1089/pop.2020.0230.

- Peterson C, Li M, Xu L, Mikosz CA, Luo F. Assessment of Annual Cost of Substance Use Disorder in US Hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;1;4(3):e210242. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0242.

- Substance Use Disorders. Medicaid.gov. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/behavioral-health-services/substance-use-disorders/index.html.

- Kuehn BM. Massive Costs of the US Opioid Epidemic in Lives and Dollars. JAMA. 2021;25;325(20):2040. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7464.

- Gudin K, Hilborne E. Edinboro: PAINWeek Poster Number 30 - Presumptive Versus Definitive Drug Testing: What Are We Missing?

Drug monitoring’s and clinical guidelines’ role in the nation’s misuse crisis

Over the years, there has been much discussion on whether physicians should employ toxicology testing as part of opioid treatment therapies. Guidelines could be better defined, so understanding physician attitudes towards the role of clinical drug testing in safely prescribing opioids has been critical.

A recent Harris Poll survey of over 500 treating primary care physicians showed, that physicians largely believe clinical drug testing is critical for managing opioids and other prescribed controlled medications, but feel clearer guidelines are needed to help optimize its use. In fact, most (85%) physicians surveyed expressed confidence that testing aids in prescribing safely, and a similar majority (88%) believe better guidelines would help ensure testing is used equitably.

The role of guidelines impacting drug monitoring, and drug monitoring’s subsequent role in combatting the nation’s drug misuse crisis, is particularly relevant as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently updated its opioid prescribing guidelines to improve the safety and effectiveness of pain care, including with prescription opioids. Among other recommendations, the guidance states that clinicians should consider clinical drug testing (toxicology testing) before starting opioids and periodically (at least annually) during opioid therapy when there is risk of overdose due to mixing with other controlled substances.4

In addition, the use of clinical drug testing in chronic opioid therapy is recommended uniformly by medical guidelines, including from the American Pain Society (APS), American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM), American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP), American Association for Clinical Chemistry (AACC), and the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB). In fact, current clinical practice guidelines from AACC recommend that, in addition to baseline drug testing, testing should be performed throughout the year for patients prescribed controlled substances.5

About the Author

Jeffrey Gudin, MD

is a senior medical advisor to Quest Diagnostics and its Drug Monitoring and Toxicology services arm and faculty member at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in the Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative Medicine and Pain Management. Board certified in pain medicine, anesthesiology, addiction medicine and hospice/palliative medicine, Dr. Gudin is a renowned expert in pain management and opioid and prescription drug misuse and use disorders.