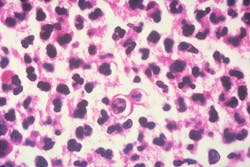

Inside all of us is an army of cells called neutrophils, primed and ready to take out any invader, be it bacteria in a wound or viruses entering our airways. As the first line of defense for the immune system, neutrophils attack and call-in reinforcements in a coordinated effort to prevent infection.

“Neutrophils are the fastest immune cells in your body, able to migrate one cell length per minute,” said Carole Parent, Ph.D. of the University of Michigan Medical School Department of Pharmacology and Cell and Developmental Biology.

Their rapid response to a site of invasion is made possible through a chemical messaging system called chemotaxis. New research from Parent and her colleagues at the U-M Medical School and the U-M Life Sciences Institute explains the precise and surprising way these chemicals are generated.

The neutrophils closest to the site sense chemicals released by the pathogens and then themselves release a different chemical called leukotriene B4 (LTB4) to bring more neutrophils to the area to eat, break down, or trap foreign material or cell debris.

The environment outside of a cell is hostile, explains Parent, so the enzymes that make LTB4 are packaged inside little circular vesicles called exosomes, which act as a sort of protective casing.

As the neutrophils migrate, they secrete these vesicles, releasing their contents to create a chemical gradient, setting off a relay that calls even more immune cells.

In a new paper published in Nature Cell Biology, the investigators describe a unique way in which exosomes from neutrophils are formed.

Instead of originating from the cell’s outer membrane, as with most other cells in the body, a neutrophil’s exosomes come from the surface of its unusually shaped nucleus.

“As someone working on cell migration my whole career, I never thought I would think about the nuclei,” said Parent. “We realized that it’s the very specific composition of the neutrophil nucleus that enables LTB4 synthesis and its packing in these nucleus-derived exosomes.”

The nucleus inside a neutrophil is malleable, its bendable shape enabling the neutrophil to squeeze into sites of infection, explains Parent. The nucleus membrane is comprised of areas rich in waxy lipid molecules called ceramides. Then, it is from these areas that buds containing the components of LTB4 are housed and eventually released from the cell to create the chemical gradient, says Parent.

Though typically a good thing in the context of infection, overexuberant neutrophils can also cause chronic inflammation, leading to such conditions as arthritis and asthma, during the execution of their predefined work.

Understanding the precise mechanism behind how neutrophils are called on opens avenues to potential drug targets, Parent said.