Key challenges of training for lab safety and COVID-19 effects

Traditionally, best practices in lab safety have included wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) while performing lab procedures in such a way as to prevent the risk of injury or transmission of infectious diseases to lab personnel. Today, lab safety includes the same practices plus new issues and challenges that lab directors must address, such as hiring and training a sufficient number of incoming lab personnel to replace staff members who are aging out into retirement.

Along with ensuring necessary workforce positional needs are met, training and proficiency of all new lab personnel are top priorities, just as in the past. However, with the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19, current learning curves in clinical labs also must incorporate procedural proficiencies that prepare all lab staff in the event of another pandemic in the future.

Lab workforce shortage

Before lab directors create or streamline training programs for additional lab personnel, their work begins with finding qualified candidates to fill key positions within the clinical lab. Current research highlights a workforce shortage among lab personnel, with some positions left unfilled for months.1

Brittany Vaughn, MHA, MLS(ASCP)SM, Global Healthcare Consultant at BD, located in Franklin Lakes, NJ, reports that “Laboratories are experiencing staffing vacancy rates that exceed the number of new graduates; coupled with high retirement rates due to an aging working population, this creates a substantial workforce shortage crisis.”1

She continued, “The workforce profile of many laboratories looks like an inverted bell curve, with a large number of technologists just starting out their career and an even larger number of highly experienced technologists preparing for retirement in the next five to 10 years. As those retirement-ready technologists move on to their next stage of life, labs commonly face challenges finding and hiring experienced and qualified replacements. It is not uncommon for certified laboratory positions to go unfilled for months due to this workforce shortage, particularly those seeking a degree of specialty experience or positioned on less-desirable overnight shifts.”

Effective training and proficiency

For labs fortunate enough to find qualified additions to their staff, the most important task at hand becomes training them. Training programs, regardless of the area of specialty, are typically only as successful as the communication of an instructor and the competence of a student. In the clinical lab, both instructor and student look to their training for safety within the lab and for helping patients waiting for a diagnosis.

Luann Ochs, MS, Product Development Manager at the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), located in Wayne, PA, pointed out that “Proper training of laboratory workers is essential to producing accurate results for patient care and is the lab’s first line of defense against errors. Robust training and competence assessment programs are an essential element of a quality management system and are required by all laboratory accreditors. Although laboratory managers know the importance of training for good quality results, competence assessment is one of the top 10 deficiencies seen by major accreditors in the U.S.2 Clearly, for many laboratories, more work needs to be done in this area.”

Training and competence assessment

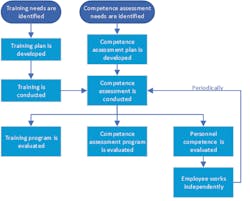

According to CLSI’s document QMS03, Training and Competence Assessment,3 “people are the most valuable resource of the organization. Effective training and competence assessment programs ensure personnel are knowledgeable and competent in their assigned roles and responsibilities.”

As such, the QM303 CLSI document lists three recommendations for effective training and competence assessment programs:

- Ensure personnel performance results in consistent, predictable, and high-quality outcomes.

- Ensure performance of assigned job tasks remains constant.

- Verify that personnel have and can demonstrate the necessary knowledge, skills, and behaviors to perform their respective duties.

Ochs adds, “And while everyone knows that training is needed for newly hired personnel, it’s also important to ensure effective training whenever organizational or technological changes occur that affect work processes, and when any employee repeatedly demonstrates performance problems. Competence should be assessed not only following a training exercise, but also periodically to ensure continued performance. Competence should also be assessed when processes or responsibilities change, as well as when any retraining needs are identified.”

According to the QMS03, “an effective training and competence assessment program can decrease the risk of a nonconforming event that could lead to an undesired patient outcome and could also have adverse financial consequences.”

Challenges of training methods

When it comes to the best training methods for lab personnel, all staff members may not respond the same way to the same methods. It is up to the lab manager to realize this and work with new hires to find a training method that allows the required training to take place in a way that benefits both the lab manager and the new staff member.

Vaughn from BD asserts, “Hiring new graduates and trainable individuals can be a prerequisite for a steeper learning curve, resulting in increased training efforts, which more often than not are short cut due to a lack of time due to the staffing challenges. There are, however, a couple of different approaches available in a laboratory manager’s toolbox to counteract this downward spiral:

- Defining a clear career pathway for non-certified employees within the lab to encourage advancement into a technologist role through partnership with an MLS or MLT teaching program, or by providing an opportunity to gain the necessary full-time clinical experience required to qualify for alternate certification routes through the American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP). The respective employees would contractually guarantee to remain employed by the laboratory for a set amount of years, if the laboratory sponsors their education. Having defined career pathways can create a steady feed of employees to pull from as retirements and other openings present themselves.

• (When considering this approach, it is important for laboratories to support their employees by providing access to education and training for the scientific theory behind the work they are doing as well as teaching how the work performed ties into the greater picture of patient care.)

- Adopting new automated technology in the laboratory will free up resources to be reallocated into full- or part-time training roles, allowing for greater and more focused attention on the training process.

- Bringing experienced technologists back after retirement, or incentivizing them to stay on longer prior to retirement, by offering part-time training roles to bridge the knowledge gap and allow them to pass on the baton.

- Exploring new training methods that allow the trainees to access training content from their mobile devices will appeal to different training styles, as well as allow the trainings to be executed more frequently. Video-recorded training is a successful method for ensuring consistency of material shared with students.”

Effects of COVID-19 on lab safety

With almost a year of dealing with SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 on a daily basis, it would seem that lab personnel have a good understanding of the virus and its subsequent disease. However, the reality is that there is still much to learn from this pandemic that continues to be responsible for infections and deaths every day around the world.

Reminding clinicians about the risk of COVID-19 transmission, CLSI’s Ochs points out that “Although the general transmission of COVID-19 is typically through respiratory droplets, laboratory workers are at risk of infection through aerosolization, splattering, and splashing of laboratory specimens. This can occur whenever samples are being handled, but especially when samples are being opened and prepared for testing. Precautions must be taken to prevent exposure from accidental sample contact.”

According to another CLSI document, M29, Protection of Laboratory Workers From Occupationally Acquired Infections, “facial barrier protection should be used if there is a reasonably anticipated potential for splattering or splashing blood or body substances or any liquid suspected of containing infectious agents.” It goes on to say that “a plastic face shield provides the best facial protection,” 4 and that splashguards may serve as an acceptable alternative to plastic face shields, but neither face shields nor splashguards are protective enough when it comes to aerosols. When aerosols are a concern, respirators are needed, or all work can be performed within a biological safety cabinet (BSC).

Ochs summarizes, “The M29 guideline encourages labs to be prepared for dealing with infectious agents by preparing a biological hazard assessment before a hazard actually occurs. Factors to consider include possible routes of transmission, including portals of entry through which pathogens can enter the body; possible agents that could be encountered and their pathogenicity; and the work environment, including the facility, procedures, and the availability and use of PPE. All of these factors contribute to the overall level of hazard to which an individual laboratory worker may be exposed.”

“In addition, according to M29, negative factors in the laboratory environment can affect the behavior of staff (e.g., poor workflow, poor housekeeping, insufficient space in the BSC). The nature of the work itself (e.g., high stress, high volumes of samples and workload, lack of time for adequate training or attainment of competency, repetitive nature of routine procedures) can lead to a false perception of safety. This perception can lead to complacency and unknowingly increase the risk of exposure (e.g., disruption of air barrier in the BSC, assumptions that PPE are performing properly),4 she added.

References:

- Flanigan, J. (n.d.). Addressing the Clinical Laboratory Workforce Shortage. Retrieved April 15, 2020, from https://www.ascls.org/position-papers/321-laboratoryworkforce/440-addressing-the-clinical-laboratory-workforce-shortage.

- Chittiprol S., Bornhorst .J, Kiechle F. Top Laboratory Deficiencies Across Accreditation Agencies. Clin Lab News. AACC Press: https://www.aacc.org/publications/cln/articles/2018/july/top-laboratory-deficiencies-across-accreditation-agencies. July 1, 2018. Accessed on August 28, 2020.

- CLSI. Training and Competence Assessment. 4th ed. CLSI guideline QMS03. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2016.

- CLSI. Protection of Laboratory Workers From Occupationally Acquired Infections; Approved Guideline—Fourth Edition. CLSI document M29-A4. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2014.