How the clinical laboratory can contribute to providing value-based healthcare

The future of healthcare will put patient health outcomes at the center of reimbursement—a concept that is commonly known as value for service. Even as far back as 2009, Michael Porter wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine, “The central focus must be on increasing value for patients—the health outcomes achieved per dollar spent.”1

How, for decades, a volume-based reimbursement model survived and even flourished—while increasingly leaving more and more people financially unable to get adequate medical coverage (if any at all)—is a huge topic in itself. This leads to the issue raised by the title of this article.

It seems that in the current climate many are waiting for the government to guide the healthcare delivery system along this path, but private industry is also taking the lead. Recently industry giants Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and Chase formed a healthcare alliance with the goal of “creating an independent company that is free from profit-making incentives and restrictions”2 in an attempt to bring affordable healthcare to their employees. In addition, the state of Colorado recently attempted to move ahead of any Federal mandate by trying to implement its own solutions to lower healthcare costs.3 Clinical laboratories, regardless of where they are located, can contribute now to this new value-based healthcare for their communities.

Finding value in data

If laboratories have a lot of anything, it is data. For years, we have been pushing data out to paper, providers, public health departments, and EMRs. Throw in Health Information Exchanges, Accountable Care Organizations, and whatever comes next, and it seems that everyone wants what we have to offer. Unfortunately, we often do not realize the value of the data we create each day and how we can use it. The key to finding value in the data starts in the questions we are asking of it.

For our laboratory, affiliated with Delta County Memorial Hospital in Delta, Colorado, we identified two very straightforward criteria: (1) the data must be quantifiable; and (2) it must save the community money. We then sought an answer in the data to a specific question: “How much does a positive influenza A and B test result cost the community?” Harvesting the data was not quite as straightforward as we had anticipated, as the influenza test changed departments from microbiology to the main laboratory during the study. However, that was only a small setback and did not influence the outcome.

Gathering the data

We started with a 2016-2017 seasonal review of influenza A and B test results and presented our findings to hospital administration. They were impressed by our presentation and asked us to expand our study to include the last five years (2012-2017). We looked at the numbers and structured our study by analyzing how many tests were ordered over the years, months, age distribution, gender, and flu type. Gathering and processing this information was straightforward and did not involve the need for any specialized support from any outside group, but was a shared project between laboratory and IT departments. The key finding that helped answer our question was derived when we looked at the number of positive tests compared to the total number of tests ordered (positivity rate) by month, or how many tests must be run before a positive result is found. So, if one test out of five ordered was positive, and each test cost $40 to run, then the cost to the community for the diagnosis of a positive result was $200. We determined the cost figure by including the hands-on time to run the test at $25/hour (that includes an average of MT and MLT wage) plus the cost of the kit. These numbers are readily determinable by any laboratory.

The question and the answer

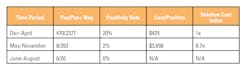

When charted, our results told us immediately of an opportunity. For each of the five years, we found three consistent times or zones of positivity. The highest zone of positivity was obviously during “flu season” and for our geographic area (rural western Colorado) was between December and April. The second zone of positivity was May to November, which was significantly lower. The third zone was a subset of the second zone and was the summer months from June through August. This zone showed no positive results and had the fewest tests run by month, which was to be expected. Table 1 shows the positivity rates by time period.

Table 1. Cost by season

Each positive result during the flu season cost the community $425 (one in five tests). During the non-flu season (May to November) as defined by our study, that cost jumped 8.7-fold to $3,698 to diagnose a positive result (one in 37 tests). During the summer months, there were no positives at all, even though some tests were still ordered.

These findings suggest that a more judicious use of influenza testing during the non-flu season months could save healthcare dollars for the community. In addition, based on the five-year trends, the recommendation should be to not test for influenza during the summer months.

The lab’s important role

It is important to understand that the laboratory does not dictate what test should be performed or not (for the most part) but may play an important role in proposing ways for better test ordering practices through analytic studies. This simple study looking at seasonal ordering patterns and positivity rates for influenza testing is just one example of the way laboratories may contribute by sharing cost-saving information and better outcomes to providers in their local communities. The decision to determine which laboratory tests to perform and when is still the providers’ responsibility.

Earlier in the now-fading era of payment by volume, this information would not have been of interest to providers or administration, as it would have meant a reduction in an almost guaranteed reimbursement. However, as we move to a value-based reimbursement model, it is not just a matter of how we get paid. Human labor resources, time, and supplies all come into play as we try to reduce healthcare costs and save money for our communities while we provide exceptional levels of healthcare. While the exact definition of “value” is still a work in progress and will no doubt continue to evolve, laboratories can play a significant role in contributing to this goal now without waiting for top-down mandates from federal or state officials. By analyzing the data we have, and suggesting more effective test utilization for our providers, we can contribute to reducing unnecessary costs to our communities and at the same time improve the efficiencies and value of the delivery of healthcare.

REFERENCES

1. Porter M. A strategy for healthcare reform—toward a value-based system. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:109-112.

2. Industry Watch: Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, Chase form healthcare alliance. HMT. 2018;39(2):4.

3. Ingold J. ColoradoCare measure amendment 69 defeated soundly. The Denver Post. November 9, 2016.