NIH scientists discover pathway that coronaviruses use to exist cells

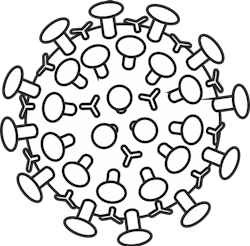

Researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have discovered a biological pathway that the novel coronavirus appears to use to hijack and exit cells as it spreads through the body. A better understanding of this important pathway may provide vital insight in stopping the transmission of the virus-SARS-CoV-2-which causes COVID-19 disease, according to a press release.

In cell studies, the researchers showed for the first time that the coronavirus can exit infected cells through the lysosome, an organelle known as the cells' "trash compactor." Normally the lysosome destroys viruses and other pathogens before they leave the cells. However, the researchers found that the coronavirus deactivates the lysosome's disease-fighting machinery, allowing it to freely spread throughout the body.

Targeting this lysosomal pathway could lead to the development of new, more effective antiviral therapies to fight COVID-19. The findings, published today in the journal Cell, come at a time when new coronavirus cases are surging worldwide, with related U.S. deaths nearing 225,000.

Scientists have known for some time that viruses enter and infect cells and then use the cell's protein-making machinery to make multiple copies of themselves before escaping the cell. However, researchers have only a limited understanding of exactly how viruses exit cells.

Conventional wisdom has long held that most viruses-including influenza, hepatitis C, and West Nile-exit through the so-called biosynthetic secretory pathway. That is a central pathway that cells use to transport hormones, growth factors, and other materials to their surrounding environment. Researchers have assumed that coronaviruses also use this pathway.

But in a pivotal experiment, Nihal Altan-Bonnet, PhD, Chief of the Laboratory of Host-Pathogen Dynamics at the NIH's National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and her post-doctoral fellow Sourish Ghosh, PhD, the study's main authors, found something different. She and her team exposed coronavirus-infected cells (specifically, mouse hepatitis virus) to certain chemical inhibitors known to block the biosynthetic pathway.

"To our shock, these coronaviruses got out of the cells just fine," Altan-Bonnet said. "This was the first clue that maybe coronaviruses were using another pathway."

To look for that pathway, the researchers designed additional experiments using microscopic imaging and virus-specific markers involving human cells. They discovered that coronaviruses somehow target the lysosomes, which are highly acidic, and congregate there. That finding raised yet another question for Altan-Bonnet's team: If coronaviruses are accumulating in lysosomes and lysosomes are acidic, why are the coronaviruses not destroyed before exiting?

In a series of advanced experiments, the researchers demonstrated that lysosomes get de-acidified in coronavirus-infected cells, significantly weakening the activity of their destructive enzymes. As a result, the viruses remain intact and ready to infect other cells when they exit.

The researchers also discovered that disrupting normal lysosome function appears to harm the cells' immunological machinery. "We think this very fundamental cell biology finding could help explain some of the things people are seeing in the clinic regarding immune system abnormalities in COVID patients," Altan-Bonnet said. This includes cytokine storms, in which an excess of certain pro-inflammatory proteins in the blood of COVID patients overwhelm the immune system and cause high death rates.