Bedside blood glucose testing in critically ill patients

CONTINUING EDUCATION

To earn CEUs, visit www.mlo-online.com under the CE Tests tab.LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. Define what constitutes a critically ill patient population and discuss the use of handheld blood glucose monitors in critically ill populations.

2. Discuss agencies that regulate off-label device use and identify the guidelines that laboratories must adhere to, in order to be compliant with off-label device use.

3. Recognize the characteristics of diabetes statistics as the relate to healthcare and morbidity.

4. List testing methods for diagnosing and monitoring diabetes and define the limitations with each method.

Studies have demonstrated that the practice of hospital bedside blood glucose testing is a necessary and effective means of managing and monitoring glycemic control. Protocols vary by institution, but there is general consensus among providers that this process is an essential component of patient care. However, the use of handheld blood glucose meters within some critically ill patient populations has resulted in varying degrees of confusion about off-label use and potential discrepancies in results.

As the most widely used option for measuring blood glucose at the point-of-care (POC), handheld meters offer the benefits of portability, ease of use, and procurement of quick results (less than 10 seconds) using small samples of capillary blood that can be obtained for frequent measurements. Testing can be performed by nurses, medical assistants, and technicians, and entails low risks of blood loss and arterial line infection. In comparison, core lab testing using arterial or venous blood involves a higher degree of complexity, along with the requirement that testing be performed by appropriately trained, qualified personnel.

Under most circumstances and conditions, handheld blood glucose testing meters can provide reliable readings with a high degree of accuracy. In a hospital setting, there are certain factors, including user errors in preparation and testing, that can contribute to inconsistent results: low hematocrit levels; the presence of vasopressors, ascorbic acid and other drugs; and the use of capillary blood specimens as opposed to arterial or venous blood samples. These factors can potentially lead to incorrect insulin administration or other treatments among specific populations of patients—namely, those who may be considered critically ill. In turn, this has created confusion among hospital staff and laboratorians across the country about the appropriate use of handheld blood glucose meters for critically ill patients.

Defining “critically ill”

The first step in providing clarification is to define what critically ill means for the purpose of blood glucose monitoring. Generally speaking, critically ill status can be determined by two considerations — the patient’s location (usually within an ICU or other acute-care department) and the patient’s health condition—or a combination of these criteria. In either category, critically ill should be defined in such a way as to identify patients in which POC glucose testing using a handheld meter is likely to yield erroneous results.

It’s important to note that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not cleared any commercially available handheld blood glucose meter for use in testing capillary whole blood specimens collected from critically ill patients, meaning this practice would be considered off-label regardless of the meter. The probability for testing errors is highest when capillary blood samples are collected from patients who have impaired peripheral perfusion, which can occur when the conditions of dehydration, shock or hypotension, or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic shock are present. These conditions most commonly occur in critical care or acute care settings.

The definition of exactly what constitutes “critically ill” can vary by institution. For instance, some hospitals may define “critically ill” as any patient who has a mean arterial pressure of less than 60 mmHg with requirements for vasopressors; other institutions may consider any patient who is in the ICU and has an arterial line or a central venous catheter as “critically ill.” In any event, the definition should easily allow any provider to quickly identify patients who have impaired peripheral perfusion secondary to hypotension/shock.

Within this critically ill patient population, capillary blood specimens for glucose testing via handheld meter may not yield accurate measurements, and providers should default to the use of arterial or venous blood specimens to achieve the most reliable results. It is impossible to predict exactly which patient with impaired peripheral perfusion is going to have erroneous capillary POC results, and of what magnitude, if any, the error will be.

For example, you could have two patients in shock, both with a mean arterial pressure of less than 60 mmHg. One patient’s capillary blood glucose result could be completely in agreement with a central laboratory measurement of glucose, while the other’s could be discordant to the point of clinical concern. There is no indisputable way to anticipate the probability of error, or to quantify it in definitive terms. Therefore, restricting use of capillary blood in patients with impaired peripheral perfusion is a reasonable thing to do to mitigate the risk of erroneous POC glucose values.

Off-label use

This all leads to the big question that is causing so much confusion among providers: Is using a handheld blood glucose meter in critically ill patients considered off-label, and if so, how does a hospital maintain compliance if it chooses to use the meter in this manner? The term “off-label” is most commonly used with reference to drugs, not devices, muddying the waters of interpretation even more. Some scenarios that could be viewed as off-label use include the use of an alternative specimen type, alternative collection site, modification of test reagents or measurement parameters, use of the device in unintended patient populations, or use of the device as a diagnostic test if it was originally intended to be used as a screening tool.

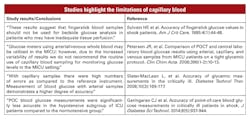

For the vast majority of providers conducting POC testing, the primary issue is compliance with accreditation standards, and this is a legitimate concern. Good data indicates that capillary blood has limitations for certain conditions that should be taken into consideration in blood glucose testing, and limiting use of capillary blood in certain situations may be recommended.

In October 2016, the FDA published a set of guidelines for manufacturers that are intending to label and market new handheld blood glucose meters for hospital use. In this document, the FDA indicated that glucose meters intended for hospital use should be evaluated differently and more stringently than those intended for physician office use or patient self-monitoring. The uncertainty, though, lies in the fact that this document has no real bearing on the current state of affairs regarding devices already at use in the market, and its use as a validation protocol for clinical laboratories is not feasible.

POCT tips

For point-of-care blood glucose meters with critically ill patients:

1. Clearly define what “critically ill” means within your institution for the purposes of blood glucose testing.

2. Consider an alternative blood glucose testing method in critically ill patients (e.g., using an arterial or venous blood sample instead of a capillary blood specimen).

3. Remain compliant by performing CLIA-required validation studies to satisfy high complexity testing requirements.

CMS interpretation

The original language in the Code of Federal Regulations as outlined in CLIA 88 speaks to modification of a testing device and indicates that changes must be validated to demonstrate that they still provide a robust, clinically appropriate measurement. By this guideline, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) could interpret modification to mean use of a device in a population of patients not specified in the package insert.

CMS maintains its position that any deviation from the manufacturer’s package labeling may constitute off-label use of the device, which means it automatically defaults to the high complexity category. But there is no hard-and-fast rule across the board. Each of the major handheld blood glucose meters currently on the market today has its own unique package insert language, leaving each open to some degree of interpretation. This creates confusion about exactly what off-label use involves.

Glucose meters are generally labeled for the quantitative measurement of glucose in whole blood. Most indicate that the meter is not to be used for the diagnosis of diabetes, but rather as a tool to monitor the effectiveness of diabetes control programs. This language stems from the original intent of the devices to be used at home in the self-management of blood glucose concentrations in patients previously diagnosed with diabetes.

Hospital glucose meters are arguably used on almost all patients in the facility, not strictly for diabetes control, but rather for the management of dysglycemia. Some meter package inserts include a clause that states the device has not been evaluated for use in critically ill patients. Only one glucose meter manufacturer has secured approval from the FDA for use throughout the hospital, including critically ill patient populations, when using arterial and venous blood specimens. No glucose meter manufacturer has secured approval from the FDA for use of capillary blood samples from patients who are considered critically ill.

From the current CMS perspective, if providers use a waived handheld blood glucose meter with labeling restrictions or limitations in patients defined as critically ill, it’s considered off-label use and immediately defaults to high complexity, which entails lab compliance with CLIA requirements for high complexity testing. At this point, only qualified personnel who have been trained as medical technologists, or individuals who hold a bachelor’s degree with an appropriate amount of science course work, can operate the meter in a population defined as critically ill. Additionally, the off-label use must then require full validation via method evaluation studies including but not limited to accuracy studies, precision studies, and analytical sensitivity and specificity studies. These studies are typically performed by the manufacturer and submitted to the FDA as part of the device review and labeling process.

How to stay compliant

Under CLIA protections, labs have the ability to go off-label at their own discretion, but they also must then adhere to all of the appropriate standards and rules as outlined by CLIA and CAP with respect to validations, personnel, training, competency, and periodic method evaluations of the device. Choosing to ignore these rules can result in severe consequences that may include citations and threats to accreditation. Habitual disregard of these standards can lead to the downstream effects of discredited lab reputation, CLIA license default, and even federal intervention.

Overcoming resistance to change is another wrinkle in the debate about the use of handheld blood glucose meters. Providers are always striving to find a balance between remaining compliant and ensuring optimal patient care. If clinicians aren’t properly convinced about—or even aware of—the limitations regarding capillary blood use for handheld glucose meter testing in critically ill patients, they may continue to perform these tests as they’ve always done in the past under the premise of interest in patient care. And, providers may struggle to understand why capillary blood is suddenly no longer permissible, when in their own personal experience, they’ve never had a problem using it before.

Achieving the best solution for the institution may require laboratory management to educate clinical and administrative staff about the limitations involved in using capillary blood specimens of critically ill patients for handheld blood glucose meter testing. Critical care doctors also have a valuable opportunity to play a role in drafting the definition of “critically ill” for purposes of blood glucose meter testing. Obtaining consensus on that definition within individual institutions is a strong first step toward eliminating a great deal of confusion about this ongoing issue.

The bottom line? Experience proves that blood glucose testing performed bedside using a handheld meter offers great value within the hospital setting. But care should be taken in determining whether capillary blood glucose measurements are the best choice among critically ill patient populations with impaired peripheral perfusion. In these cases, using an arterial or venous blood sample instead of a capillary blood specimen may be well advised. Institutions that decide to use a handheld blood glucose meter for any purpose possibly considered off-label should then follow the appropriate measures to remain compliant without compromising patient care.

T. Scott Isbell, PhD, DABCC, FACB, is an Assistant Professor of Pathology and the Medical Director of Clinical Chemistry and Point of Care Testing at SSM Saint Louis University Hospital. He directs the Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory in the Department of Pathology, and is the Director of POCT at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital. An active member of the AACC, Dr. Isbell is the past chair of the Critical and Point of Care Testing Division and a member of the SYCL Core Committee.