Influenza symptoms and the role of laboratory diagnostics

Here’s the latest from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on influenza diagnostics, adapted from www.cdc.gov and abridged for space.

Signs and symptoms

Influenza illness can include any or all of these symptoms: fever, muscle ache, headache, lack of energy, dry cough, sore throat, and possibly runny nose. The fever and body aches can last three to five days, and cough and reduced energy may last for two weeks or more. Influenza can be difficult to diagnose based on clinical symptoms alone because the initial symptoms can be similar to those caused by other infectious agents including, but not limited to, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, parainfluenza viruses, and Legionella spp.

Appropriate treatment of patients with respiratory illness depends on accurate and timely diagnosis. Early diagnosis of influenza can reduce the inappropriate use of antibiotics and provide the option of using antiviral therapy. However, because certain bacterial infections can produce symptoms similar to influenza, bacterial infections should be considered and appropriately treated, if suspected. In addition, bacterial infections can occur as a complication of influenza.

Influenza surveillance information and diagnostic testing can aid clinical judgment and help guide treatment decisions. Influenza surveillance by state and local health departments and the CDC can provide information regarding the presence of influenza viruses in the community. Surveillance can also identify the predominant circulating types, influenza A subtypes, and strains of influenza.

Diagnostic lab procedures

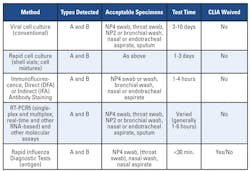

A number of tests can help in the diagnosis of influenza (Table 1). However, tests do not need to be done on all patients. For individual patients, tests are most useful when they are likely to give a doctor results that will help with diagnosis and treatment decisions. During a respiratory illness outbreak in a closed setting (e.g., hospitals, nursing homes, cruise ships, boarding schools, summer camps) however, testing for influenza can be very helpful in determining whether influenza is in fact the cause of the outbreak.

Preferred respiratory samples for influenza testing include nasopharyngeal or nasal swab and nasal wash or aspirate, depending on which type of test is used (Table 2, page 14). Samples should be collected within the first four days of illness. Rapid influenza diagnostic tests provide results within 15 minutes or less; viral culture provides results in three to ten days. Most of the rapid influenza diagnostic tests that can be done in a physician’s office are 50 percent to 70 percent sensitive for detecting influenza and greater than 90 percent specific. Therefore, false negative results are more common than false positive results, especially during peak influenza activity.

Diagnostic tests available for influenza include viral culture, serology, rapid antigen testing, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunofluorescence assays, and rapid molecular assays. Sensitivity and specificity of any test for influenza might vary by the laboratory that performs the test, the type of test used, and the type of specimen tested. Among respiratory specimens for viral isolation or rapid detection, nasopharyngeal specimens are typically more effective than throat swab specimens. As with any diagnostic test, results should be evaluated in the context of other clinical and epidemiologic information available to healthcare providers.

Viral culture

Despite the availability of rapid influenza diagnostic tests, collecting clinical specimens for viral culture is critical, because only culture isolates can provide specific information regarding circulating strains and subtypes of influenza viruses. This information is needed to compare current circulating influenza strains with vaccine strains, to guide decisions regarding influenza treatment and chemoprophylaxis, and to formulate vaccine for the coming year. Virus isolates also are needed to monitor the emergence of antiviral resistance and the emergence of novel influenza A subtypes that might pose apandemic threat.

During outbreaks of respiratory illness when influenza is suspected, some respiratory samples should be tested by both rapid influenza diagnostic tests and by viral culture. The collection of some respiratory samples for viral culture is essential for

determining the influenza A subtypes and influenza A and B strains causing illness, and for surveillance of new strains that may need to be included in the next year’s influenza vaccine. During outbreaks of influenza-like illness, viral culture also can help identify other causes of illness.

RIDTs

Commercial rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs) are available that can detect influenza viruses within 15 minutes. Some tests are approved for use in any outpatient setting, whereas others must be used in a moderately complex clinical laboratory. These RIDTs differ in the types of influenza viruses they can detect and whether they can distinguish between influenza types. Different tests can detect 1) only influenza A viruses; 2) both influenza A and B viruses, but not distinguish between the two types; or 3) both influenza A and B, and

distinguish between the two.

None of the tests provides any information about influenza A subtypes. The types of specimens acceptable for use (i.e., throat, nasopharyngeal, nasal aspirates, swabs, or washes) also vary by test. The specificity and, in particular, the sensitivity of RIDTs are lower than for viral culture and vary by test. Because of the lower sensitivity of the RIDTs, and thus the possibility of false-negative rapid test results, physicians should consider confirming negative tests with viral culture or other means, especially during periods of peak

community influenza activity.

In contrast, false-positive rapid test results are less likely, but they can occur during periods of low influenza activity. Therefore, when interpreting results of a rapid influenza diagnostic test, physicians should consider the positive and negative predictive values of the test in the context of the level of influenza activity in their community. Package inserts and the laboratory performing the test should be consulted for more details regarding use of rapid diagnostic tests.

Serologic testing

Routine serological testing for influenza requires paired acute and convalescent sera, does not provide results to help with clinical decision-making, is only available at a limited number of public health or research laboratories, and is not generally recommended, except for research and public health investigations. Serological testing results for human influenza on a single serum specimen is not interpretable and is not recommended.