To earn CEUs, visit www.mlo-online.com

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Upon completion of this article, the reader will be able to:

1. State the implementation date for the CLIA IQCP.

2. Explain the general purpose and the requirements of the IQCP.

3. List the three individual parts of the IQCP and describe the purpose of each part.

4. Identify the various components that must be included in each of the three parts of the IQCP.

5. Identify the areas of the IQCP that will be reviewed for compliance by CMS and/or accrediting organizations.

6. Name the various reference or guidance documents that are available to use when preparing the IQCP.

As January 1, 2016, draws near, clinical laboratories are gearing up for the implementation of the CLIA Individualized Quality Control Plan—IQCP. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has been providing training, information and guidance since the IQCP trial period began on January 1, 2014.

Why is next New Year’s Day so significant? As of the implementation date, the IQCP will be written into the CLIA Interpretive Guidelines for Laboratories to replace Equivalent Quality Control (EQC) procedures currently described. Between now and then, laboratories may:

- Follow CLIA Quality Assurance (QA) requirements as written;

- Continue to use the current EQC procedures; or

- Implement IQCP.

After implementation, the second option will no longer be acceptable. If it is still in use, it will result in a citation for noncompliance.

IQCP: some relevant background

The CLIA Individualized Quality Control Plan (IQCP) is a risk-based, objective approach to performing quality control testing. The IQCP is based on assessment of the unique laboratory testing in use, patient populations, and other aspects (for example, internal quality checks built into new instruments). IQCPs will be implemented under the CMS regulation 42 CFR 493.1256 Standard: Control Procedures, and will apply to most CMS-certified current and new non-waived tests. They will not apply to waived tests.

While IQCP participation is voluntary, it will, as noted above, replace EQC, which was designed as a standardized approach and intended to minimize the amount of external QC required. IQCP can be thought of as a laboratory-specific tailored plan (“the right QC”) as opposed to a general, standardized plan (“one size fits all”).

Regulatory/accreditation requirements, manufacturer/product information, and the individual facility setting will all affect the development of an IQCP. However, CLIA concepts and regulations will not change, and laboratories may elect to follow current CLIA QC regulations directly in order to demonstrate compliance.

IQCP: some general observations

The Individualized Quality Control Plan is intended to provide a means for labs to assess the testing process and to make their own determination with regard to frequency of quality control (QC). Some lab leaders have pointed out, however, that the IQCP guidance,1 and the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) document that it’s based on, EP23,2 focus on pre-analytic and post-analytic processes, processes for which liquid QC has little chance of catching errors. Adding to that, there is scant information in either document to guide the lab on how to assess an appropriate QC frequency. Both documents, however, describe a good method for looking at the entire testing process, from specimen collection to reporting of results, and determining what controls, liquid and otherwise, are needed to have confidence in the quality of the results.

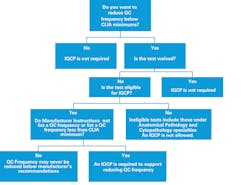

The requirements of an IQCP are straightforward. If a test is waived, an IQCP is not required. If a test is non-waived and eligible per the guidance, and the lab wishes to reduce QC below the CLIA default QC (typically two levels per day), and the manufacturer has no recommendation or a recommendation that is less than CLIA default, then an IQCP must be performed and in place starting January 1, 2016. A lab deciding to run at a QC frequency equal or greater than CLIA minimums does not have to perform an IQCP (Figure 1).

According to the guidance document, CMS surveyors will not evaluate the end result of the IQCP—that is, the validity of the type of controls in place and the frequency of QC. The surveyor will perform what is essentially an inventory of the IQCP. Are all the required components present? Does data exist to support the decision? Is the document appropriately signed and in place?

Breaking down the IQCP

There are three parts to the IQCP:

- The Risk Assessment, where potential problems that could lead to errors are identified and then classified as to their potential for causing harm.

- The Quality Control Plan, where control requirements are listed.

- The Quality Assessment, which contains the details of how the Quality Control Plan will be assessed to determine if it is functioning correctly.

Risk Assessment

The Risk Assessment (RA) is the heart of the IQCP. Hazards identified in the risk assessment process are evaluated for how frequently they may occur, how likely it is that they can be detected when they occur, and the level of severity in terms of risk to the patient.

The CMS guidance document and accrediting bodies (See “Support for Preparing IQCPs,” page 11) do not require any specific process to be followed; they do require certain components to be present and the resulting decisions to be based on information and data generated by the lab in its own environment and by its own personnel. EP23 and manufacturers provide excellent examples of a risk assessment table and risk acceptability matrix. The risk assessment must cover all three phases of testing and the five mandatory components: specimen, environment, reagent, test system, and testing personnel. CMS and accrediting organizations emphasize that labs must use their own data and procedures when assessing the process. Manufacturer information alone is not adequate for making decisions. Existing method validation and QC records will be valuable sources of data for tests that have been in use and will be converting to an IQCP. New tests are handicapped a bit because they lack the luxury of historical data. Labs should use data from the method validation process and, if necessary, devise a test protocol to produce additional data in order to make an objective decision about QC frequency.

CLSI offers a free template to help labs walk through potential sources of failure.3 The document lists more than 100 failure types for all three phases of testing. This tool can aid the IQCP team in identifying failures they may have overlooked in their process mapping.

CMS will focus on verification of the presence of all mandatory components and whether the data supporting the QC decisions is present. The agency and the accrediting organizations have indicated that they will not make judgments as to the soundness of the decisions, as that liability and responsibility lies with the laboratory director.

Quality Control Plan

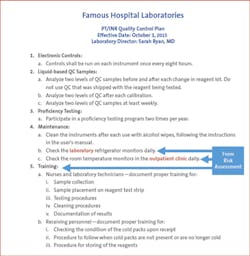

The Quality Control Plan (QCP) is the summation of the steps put in place that mitigate any unacceptable risks. It often is a one- or two-page document (e.g., Figure 2) that lists in simple statements what activities are required.

As mandated by CMS, the Quality Control Plan must include the number, type, and frequency of QC testing and the acceptance criteria. It may include other controls such as personnel training, competency assessments, electronic controls, and temperature monitoring.

The breadth of detail and order of the contents in the QCP is left to the laboratory’s discretion. Keeping it simple is always good practice for auditor-facing documents. The QCP does not need to include the risk assessment or any supporting documentation. It may stand alone or it may incorporate the Quality Assessment (QA) section (see page 11). Due to the length of the RA, the lab may wish to maintain it separately from the QCP or include a summary. Some lab directors have chosen to include a process map and risk acceptance matrix, but they simply could be referenced instead.

Each QCP must be approved, signed and dated by the laboratory director.

Quality Assessment

As with any Quality procedures, it’s important to periodically review the effectiveness of the procedure. The QCP is no different; CMS requires a Quality Assessment (QA) as part of the IQCP. The Quality Assessment section defines which aspects will be monitored and how often. In addition to a periodic review, the IQCP must be re-evaluated if there is a change to the testing process, such as the addition of new analytes or a new location.

Labs may choose to include monitors such as clinician complaints, QC data, proficiency testing reports, competency and training records, and environmental logs. If a failure of the process occurs, an investigation is commenced and findings are documented, including any changes to the IQCP. Additionally, as the CMS guidance document includes a probe asking whether, in the event of a failure, all patient test results were evaluated since the last acceptable QC, there should be a procedure defining how that evaluation is performed and documented.

Documentation summary

The CMS and/or accrediting organization surveyor will specifically review these areas of the IQCP for compliance:

- The IQCP must include three sections: Risk Assessment, Quality Control Plan, and Quality Assessment.

- The Risk Assessment must address all five required components.

- The Risk Assessment must cover the three phases of testing: pre-analytic, analytic, and post-analytic.

- The Risk Assessment must include in-house data, established by the laboratory and by its own personnel.

- The Quality Control Plan must be approved, signed, and dated by the laboratory director.

- The Quality Assessment must include a review system for the ongoing monitoring of IQCP effectiveness.

Getting started

Some labs have trouble knowing where to begin. A good case can be made that it is best to start with the Risk Assessment. Here are five prep steps that can help lab leaders to do that efficiently:

- Make a list of any tests in the lab or at the point of care that are running QC less than the CLIA minimum.

- If you are accredited, or in a state with independent requirements, call or visit the accrediting agency or state’s website to obtain the most current information on IQCP.

- Contact your test manufacturer via customer service number or your sales rep and find out if they have an IQCP guidance document or template.

- Identify your IQCP team members. Preparing an IQCP will require representative input from all staff members who are involved in the testing process. This may mean, for example, clinical staff for point-of-care tests.

- Gather applicable documents: Instructions for Use, Manuals, QC results, proficiency testing, complaints, corrective actions, competency assessment checklists, and reports—everything that might be relevant.

Now you’re ready to begin the risk assessment.

Perhaps the best piece of advice is not to let the details or remote possibilities bog you down. It’s easy to get tripped up on highly unlikely situations that could result in catastrophic patient harm. Make note of such eventualities, but focus on the daily practices and types of hazards that could reasonably occur. As valuable as it is for labs to have plans in place for rare natural disasters, for example, compelling labs to do so is not the intent of the IQCP process. Rather, the goal is to create a document that is designed to reduce the likelihood of errors that will cause patient harm in normal operations.

Creating an IQCP takes a lot of work. But lab leaders should focus on the reward that work can lead to: a QC system that is tailored to the unique needs of their lab.

References

- IQCP guidance. CMS Survey & Certification Letter 13-54, August 16, 2013. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-13-54.pdf.

- CLSI. Laboratory Quality Control Based on Risk Management: Approved Guideline, CLSI document EP23-A. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2011 CLSI sources of failure.

- EP18/EP23 Sources of Failure, Free Electronic Template. 2013. http://shop.clsi.org/method-evaluation-companion-products/EP18-a2-EP23-ws.html.

- ASM guidance. ASM collated IQCP resources for microbiology. http://clinmicro.asm.org/index.php/lab-management/laboratory-management/445-iqcp-iqcp.

- CMS brochures. CLIA Brochures 11 – 13 http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/Individualized_Quality_Control_Plan_IQCP.html.

- CMS/CDC workbook. Developing an IQCP: A Step-by-Step Guide. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/Downloads/IQCP-Workbook.pdf.

- COLA. IQCP: What you need to know. www.colainsider.com/iqcp-what-you-need-to-know/.

- TJC. Prepublication Standards – New and Revised Standards for Individualized Quality Control.

- CAP. Proposed CAP checklist requirements. www.cap.org/ShowProperty?nodePath=/UCMCon/Contribution%20Folders/WebContent/pdf/proposed-cap-checklist-requirements-iqcp.pdf.

The author gratefully acknowledges the contributions of Prof. Maria Stevens

Hardy, IMA(ASCP), AHI(AMT), CLC(AMT); Curtis Parvin, PhD; Valerie Ng, MD, PhD; and James Nichols, PhD, DABCC, FACB, whose insights and knowledge were invaluable in the development of this article.

Multiple instruments, multiple locations: multiple IQCPs?

A test device with multiple analytes may use one IQCP with each analyte reviewed in the Risk Assessment for the potential of harm to the patient. A point-of-care device that performs chemistry and cardiac panels, for instance, may have almost identical risk assessment from a process point of view but very different levels of risk of harm to the patient.

Some lab directors have questioned whether individual Risk Assessments must be conducted when identical test devices are used in multiple locations. CMS recognizes that even with identical instruments, users in different labs or clinics may have different conditions or practices. There are several ways to approach this. The IQCP team could identify what parts of the process have commonalities that would allow the section to be applicable to multiple locations, and which parts of the process need to be evaluated individually. Then individual IQCPs would be created with common sections cut and pasted from one IQCP to another and the unique sections varying depending on location.

Testing occurring under the same lab number may use one IQCP for all locations, but it must be clear that a Risk Assessment was conducted for all locations, and, where necessary, quality controls unique to each location must be clearly stated. A multisite IQCP may list common requirements in one section and then separately identify the individual locations with their site-specific requirements.

Institutions with dozens or hundreds of identical point-of-care meters (instruments) have the added challenge of determining whether all or some of the meters are tested at each QC frequency interval. This raises a question: when a frequency of QC is identified for a particular test, does that mean that all meters are tested at that frequency or just the cartridges? No clear direction has been provided. CMS and the College of American Pathologists (CAP) have said it is up to the lab to make this decision as part of its Risk Assessment and call out the requirement in the QC Plan.

One plan could be to devise a means for rotating QC across all meters over a period of time so that all meters are tested with liquid QC at a frequency which lab leaders are confident does not present an unacceptable risk—monthly, quarterly, semi-annually, etc. The lab must also identify what action is required if a meter fails the liquid QC test on its periodic check, but in the meantime, the cartridge lot has passed its regular liquid QC test on another meter. One action might be to review all patient tests since the last passing QC, which may be an interval prior to the failing QC. However, many of those patient samples may no longer be available for retesting, and therefore this may present an unacceptable risk.

Liquid QC and frequency

There is not much written describing how to use a risk-based approach specifically to determine the best frequency for liquid QC. Biostatistician Curtis Parvin, PhD, approaches this issue pragmatically. Liquid QC is designed to detect systematic failures which, when they occur, affect all subsequent test results. The most logical approach is to first know your current risk exposure.

To do that, labs need to identify the average number of patient tests run between QC events. Assuming a failure of the test system that occurs immediately after running a QC, this then is the number of patients that could be affected. From a statistical viewpoint, since a test system failure is equally likely to happen at any time from when the last QC was performed to just before the next QC is performed, statistically the expected number of results that could be incorrect is one-half the number of patient tests run between QCs. If this number and the resulting severity level is acceptable, then the QC frequency may not need to be adjusted.

If labs find this number unacceptable, they must look for ways to reduce the risk. At this point, some analysis is required. Quantitative tests should be evaluated for test performance in terms of sigma-metrics and the rules and frequency should be adjusted accordingly. Point-of-care test devices that do not permit rule selection for acceptance of QC testing should augment the built-in QC lockouts with QC records that evaluate the QC performance with rules appropriate for the sigma performance of the assay.

Additionally, a QC rule that is inadequate to catch a failure on the first QC event only compounds the problem. For example, using only a rule that triggers a violation when QC is out three standard deviations (1:3s) on a low-performing assay is unlikely to quickly identify a problem on the first QC test after the failure occurs, thus increasing the number of potentially affected patients.

Support for preparing IQCPs

- Microbiology. CMS recently revised the guidance document to remove references to CLSI microbiology documents and now requires an IQCP to be in place by January 1, 2016, or follow the applicable default QC requirements as listed in the regulation. The American Society for Microbiology (ASM) has provided some excellent guidance4 to laboratories.

- CMS Surveyed Labs. Those labs who are not in exempt states or accredited need only follow CMS guidelines. CMS and CDC have published three brochures5 on the topic and recently released a workbook6 focused at physician offices and other smaller laboratories. Using the workbook will produce a compliant IQCP, but larger labs may feel their processes demand a more rigorous approach.

- Accrediting Organizations. It appears all accrediting organizations will implement the IQCP option as written and becoming effective also on January 1, 2016. COLA7 , The Joint Commission8 , AABB, and A2LA have added no additional restrictions. The College of American Pathologists (CAP) has proposed two additional requirements beyond the CMS guidelines. First, eligibility for IQCP is restricted to devices with internal control processes such as built-in or electronic controls. Second, regardless of IQCP findings, external QC must be run at least with every new lot, new shipment, or every 31 days.9

About the Author

Andy Quintenz

serves as Scientific and Professional Affairs Manager for Bio-Rad Laboratories Quality Systems Division.