Growing up in a socioeconomically disadvantaged household may have lasting effects on children’s brain development, a large study suggests.

Compared with children from more-advantaged homes and neighborhoods, children from families with fewer resources have different patterns of connections between their brain’s many regions and networks by the time they’re in upper grades of elementary school, the research finds.

One socioeconomic factor stood out in the study as more important to brain development than others: the number of years of education a child’s parents have, according to the study led by a pair of University of Michigan neuroscientists and published in Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience.

But as the researchers dug deeper, they discovered the number of diplomas or degrees parents earned is not the only thing that can make the difference for brain connectivity. They also found a role for parenting activities, like reading with children, talking with them about ideas, taking them to museums, or other cognitively enriching activities.

The study draws on brain scans and behavioral data from more than 5,800 9- and 10-year-old children from diverse backgrounds nationwide. It’s the largest-ever look at how socioeconomic factors affect children’s “functional connectomes” – the term for maps of interconnectivity across hundreds of brain regions.

It’s also potentially relevant to public policy. One in seven American children lives in poverty using the standard definition, and half qualify for free or reduced school lunch.

The large study size was made possible by the national Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study research project, which enrolled more than 11,000 children at 22 sites nationwide – including hundreds taking part through the U-M Department of Psychiatry and Addiction Center. The new study is based on data from more than half of the participating children, including brain scans made using functional magnetic resonance imaging or fMRI.

Those scans measured the children’s brain activity when they were simply lying in the scanner, without being asked to do anything. This resting state allows neuroscientists to see the level of traffic between different areas of the brain, along functional connections that develop from before birth throughout childhood and adolescence.

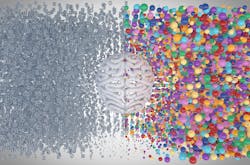

The team used machine learning to “teach” a computer to try to predict a child’s level of socioeconomic resources based exclusively on patterns of interconnections among brain regions. They showed that the patterns learned by the computer generalize to new groups of children that the computer had not “seen” before. This analysis showed wide variation in brain connectivity patterns across children of different socioeconomic backgrounds.

The researchers examined a composite measure of overall socioeconomic resources of a child’s household, combining measures of parental education, household income and levels of neighborhood resources. In addition, the researchers examined the unique contributions of each of these three socioeconomic factors.

That’s where parental education rose to the fore as the most associated with variations in brain connections.

For a subset of 3,223 children, the researchers were able to analyze additional data to explore what factors might help to explain why parental education is associated with differences in children’s brain connectivity patterns.

They found parents with higher levels of education engaged in more home-based enrichment activities, and these children scored higher on tests of cognitive function and had better grades in school.