Along with requirements for personnel qualifications and quality control testing, proficiency testing (PT) is one of the central safeguards of laboratory quality under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA)1 and its regulations.2 The CLIA regulations have often been compared to a three-legged stool, resting on requirements for personnel qualifications and two performance indicators: quality control testing and proficiency testing. Proficiency testing is the only external performance indicator required by CLIA.

Despite its central role, PT problems continue to be cited by CLIA surveyors. Among the more serious “condition level” deficiency citations given to laboratories inspected by CMS in 2012, unsuccessful PT participation and failure to enroll in PT were, respectively, the second- and third-most common citations.3 For all combined types of deficiencies cited by CMS in 2012 (condition and standard levels, combined), the third-most common deficiency was failure of laboratories to verify accuracy twice per year for analytes and tests for which participation in a PT program is not specifically required in CLIA Subpart I.3 Some of these failures may have resulted from confusion over the CLIA requirements, including the requirement in §493.1236(c) to verify test accuracy for all non-waived test systems when CLIA doesn’t specifically require participation in a PT program. This article is intended to help clarify CLIA’s current PT requirements for laboratories.

Under CLIA, all laboratories that perform non-waived testing are required to enroll in and perform PT using one of the thirteen CMS-approved PT programs (Table 1) (http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/Downloads/ptlist.pdf). Only those laboratories that hold Certificates of Waiver are exempt from the requirement to perform and pass PT. All laboratories that hold Certificates of Compliance or Certificates of Accreditation are monitored for successful PT participation by CMS or one of six CMS-approved accreditation organizations (Table 2 ) (http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/Downloads/AOList.pdf). In some cases, accreditation organizations, such as the College of American Pathologists (CAP), require their laboratories to participate in PT for more than just the CLIA-required analytes or tests. Two states, New York and Washington, have exempt status under CLIA because their requirements are judged to be at least as stringent as CLIA regulations. New York State requires laboratories to use its PT program, while Washington State allows laboratories to use any CMS-approved PT program.

| Note: √ indicates that the program offers PT in the CLIA specialty. Table 1. 2013 CMS-approved PT programs and the specialties available |

| Table 2. CMS approved accreditation organizations, 2013 |

A brief history of the conception of CLIA helps to explain the current PT rules. Congress enacted CLIA ’88 to promote uniform quality and standards among all clinical testing sites in the United States.1 Prior to passage of the 1988 Amendments, laboratories were subject to an earlier law (The Clinical Laboratories Improvement Act of 1967) that applied only to hospital laboratories and laboratories engaged in interstate commerce by performing testing on specimens that crossed state boundaries.4 Only laboratories of these types were required by federal regulations to adhere to quality standards, including performance of PT. For many reasons, it has been assumed that PT performance is an indicator of the quality of patient testing, and this has been borne out in some specific studies.5,6 Shahangian has reviewed the studies that have linked PT performance to other laboratory characteristics.7 Clearly, while CLIA has been in effect, PT scores have improved gradually. While there are, no doubt, many reasons for improved PT performance, the impact has been greatest on laboratories that had not previously been required to participate in PT before 1988.8,9

PT scoring

Laboratories must demonstrate successful PT performance to remain in good standing. Overall, successful performance is defined on the basis of satisfactory performance on individual PT events, which generally occur three times per year. In most cases, there are five challenges per analyte per event. Laboratories must get at least four of the five challenges correct (80%), or the event will be considered as unsatisfactory; for most analytes in the specialty of immunohematology, the requirement for satisfactory performance is five of five challenges correct (100%). There are no sanctions if the laboratory has an occasional, isolated unsatisfactory PT event for a specific PT analyte. However, if a laboratory has two unsatisfactory events out of three consecutive events, it will be cited with a deficiency for unsuccessful PT performance. It is important to remember that a laboratory will usually obtain a score of 0% for an event if it does not submit its results to the PT program on time or fails to submit them at all.

For several possible reasons, PT challenges or events may occasionally not be graded, or there may be other variations in normal scoring that affect either all participants or specific laboratories. For example, if there is a problem with one or more challenge samples, perhaps due to contamination, which results in failure to achieve the required consensus to assign the target values to those sample(s), then all participants will pass the event with a 100% score. In other instances, individual laboratories may temporarily be excused from participating in PT, such as a case in which an analyzer is being repaired and not being used for patient testing or a natural disaster has occurred. In this type of extenuating circumstance, the laboratory can avoid an unsatisfactory score (and possibly the more serious unsuccessful score) provided it notifies CMS or its accreditation organization when factors beyond its control prevent normal performance of PT.

The mechanism for scoring challenges depends upon whether the analyte is qualitative or quantitative in nature. Many times, qualitative analytes have only two possible answers—for example reactive/nonreactive or positive/negative. In addition, in the specialty of hematology, the presence or absence of a certain cell type or the correct identification of various cells or cell inclusions are considered qualitative results. To be considered a correct PT result the answer must match the qualitative target value, i.e., the result that is considered to be correct. For qualitative analytes, the target value is determined by the overall participant consensus, or it may be established by a group of at least ten referee laboratories selected by the PT program. In either case, a minimum of 80% consensus is required to grade the challenge.

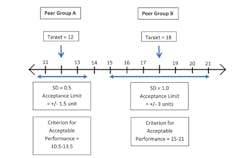

The results for quantitative analytes, those reported in numerical values, are treated differently. As with qualitative analytes, for quantitative analytes the target value may be set using the overall average of participant responses, after removal of outliers, or it may be established by a minimum of ten referee laboratories. Although CLIA established the idea that a National Reference System for the Clinical Laboratory would use definitive or reference methods to establish targets, that approach was not possible, and it is uncommon to set the target value using a reference method. Quantitative analytes are not graded if there is not at least 80% agreement, which in this case means at least 80% of results are within the criteria for acceptable performance as specified in Subpart I of the CLIA regulations (Table 3 and Figure 1).

| Table 3. Analytes or tests for which proficiency testing participation is required per CLIA Subpart I |

Although PT programs may use either of the two approaches mentioned above to set the target value for quantitative analytes, they most frequently peer group results based upon their use of a common method platform and/or reagents to establish target values and determine whether each peer group can be graded based on the requirement for 80% of results to fall within the acceptance limits. Therefore, for a particular challenge, there may be a dozen or more peer groups, each with a separate target for acceptable performance. In this case, laboratories’ results are judged against the average results in their peer group. Peer grouping was determined to be necessary for many analytes because the modified constituents of PT samples can sometimes affect test results (matrix effects), and these inaccuracies cannot be corrected. The causes of matrix effects can include lyophilization (freeze-drying), addition of stabilizers and preservatives, and other manipulations that cause PT materials to behave differently than unmodified patient specimens.10,11

In addition to differences in the matrix that can alter test results between test systems, inherent differences in the measured entity can differentially affect test results depending upon the test system used.10 For example, when the measured entity is an enzyme, in order to get sufficiently elevated concentrations of that enzyme in PT samples it may be necessary to add concentrated enzyme materials that behave differently than unmodified patient specimens. These materials can work well to assess relative accuracy within a peer group, but they may not be useful to assess absolute accuracy if they are not commutable with patient specimens. The term “commutability” means that PT specimens behave like patient specimens when tested on different test systems. Commutability of PT specimens cannot be assumed unless unaltered patient specimens are used in PT, and this has not been possible for large scale PT programs, except in a few cases. Miller et al showed the viability of using patient materials for PT.12

Recently, the CAP has initiated an “accuracy based” approach for a limited number of PT analytes. It uses unmodified patient materials that are not subject to matrix effects, so that there is only one target value, with no need for peer-grouping.13 Early results suggest that this approach is feasible, at least on a limited scale. The advantage is that real differences between peer groups, for example due to calibration errors, are not ignored under the guise of matrix effects. CLIA does not require the use of unmodified, accuracy-based PT, but it is certainly permissible.

So far, we have discussed the target value for PT scoring. The other concept that is important for establishing a criterion for acceptable performance for each analyte or test is the acceptance limit. Together, the target and acceptance limit constitute the criterion for acceptable performance (Figure 1). For each of the approximately 100 required PT analytes, CLIA regulations specify the acceptance limit (+/-) around the target value that must be used by all CMS-approved PT programs (Table 3). Although PT programs have latitude in how they assemble peer groups, they must use the acceptance limits specified in Subpart I of CLIA for each required analyte. Acceptance limits are variously listed as percentages, concentration limits, or standard deviations. In several cases, mixed criteria are used to accommodate the relatively greater error observed at low concentrations for most test systems. Simple qualitative analytes allow only two ways results can be reported, while acceptance limits for tests expressed as dilutions are typically plus or minus two dilutions.

Other PT requirements

Laboratories must be sure they are aware of all the required PT analytes listed in the regulations and enroll in a PT program for those analytes if they perform patient testing for them. CLIA requires that PT samples be tested in the same manner as patient specimens. For example, testing must be performed by integrating the sample into the normal patient workload, without assigning to the “best techs” for analysis, and without repeat testing, unless repeat testing is routinely performed on patient specimens. Of course, relevant documentation must be retained. For more explanation on the rules that apply to PT, readers are referred to Interpretive Guidelines for Laboratories and Laboratory Services (Appendix C) of the CLIA regulations (http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/Interpretive_Guidelines_for_Laboratories.html) or the CMS CLIA brochure on PT (http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/Downloads/CLIAbrochure8.pdf).

PT referral is prohibited

Because of the high priority Congress put on PT as a measure of laboratory performance, CLIA is especially stringent concerning PT referral. No flexibility in the application of sanctions was given to CMS to allow for cases in which a laboratory might arguably have been acting in good faith and intended merely to treat the PT sample as it would treat a patient specimen, including referring it to another laboratory for additional testing. It is important to avoid splitting a PT specimen for testing with any other laboratory that has a different CLIA number, whether internal or external to your laboratory system. Likewise, laboratory staff may not discuss PT results with laboratories in their system that have a different CLIA number or with external laboratory staff, as may be possible when they work two jobs.

An amendment to the CLIA law, the “Taking Essential Steps for Testing (TEST) Act of 2012,” H.R. 6118 (8), signed by President Obama in December 2012, is intended to provide the Secretary of Health and Human Services with some discretion in the enforcement due to unintentional PT referral. The Test Act clarifies that sending (“referring”) a CLIA PT sample to another laboratory for analysis is prohibited despite the requirement that PT samples be treated like other specimens; gives the Secretary discretion as to whether to revoke a laboratory’s CLIA certificate for one year in the case of a PT referral violation (replacing mandatory revocation); and gives the Secretary discretion to substitute intermediate sanctions in lieu of a mandatory two-year ban on a laboratory’s owner/operator when the laboratory’s CLIA certificate is revoked for this reason.

Special cases

Microbiology

Under CLIA, microbiology does not have specific PT analytes as indicated for other laboratory specialties. Rather, CLIA requires laboratories to enroll in PT for each subspecialty of microbiology (bacteriology, mycobacteriology, mycology, parasitology, and virology) for which they perform testing. It would not be feasible to require laboratories to test five challenges for every organism they might possibly encounter. Instead, the focus is on demonstrating overall proficiency to perform certain stains, detect or identify organisms in each subspecialty, and, in some cases, perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing, consistent with the laboratory’s level of service for patient testing.

Gynecologic cytology

Cytology differs from other specialties in that individual cytotechnologists and cytopathologists who screen gynecologic cytology specimens (Pap tests) must participate in on-site PT at least once per year. Individuals who do not achieve a passing score of 90% on the annual ten-slide test set must be retested. If the individual does not achieve a passing score on the second test, he or she must receive remediation, and gynecologic slides he or she examines must be rescreened before the individual is again retested using a 20-slide test set. If the individual does not achieve a passing score on the third test, he or she must cease examining gynecologic slides and receive 35 hours of continuing education in diagnostic cytopathology that focuses on the examination of gynecologic slides. The individual may not resume examining gynecologic slides until he or she achieves a passing score of 90%. If the laboratory fails to ensure that individuals are tested and obtain the applicable retesting and required remediation, CMS will initiate immediate sanctions or limit the certificate to exclude cytology and may suspend Medicare and Medicaid payments for cytology testing.

Immunohematology (blood banking)

Immunohematology differs from other specialties because for selected analytes, there is no allowance for errors. For each PT event, the criteria for acceptable performance for ABO group, Rh typing, and compatibility testing is 100% accuracy. For these analytes, a PT program must compare the laboratory’s response for each analyte with the response that reflects 100% agreement of ten or more referee laboratories or 95% or more of all participating laboratories to be considered satisfactory. For identification of unexpected antibodies, the requirement for satisfactory performance in the event is the same as other specialties: 80% of challenges must be correct.

Common QuestionsWhat if I have questions that are not addressed in this article? Readers can refer to a CMS “Frequently Asked Questions” sheet that may address most of the questions they may have that are not covered here: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/downloads/cliabrochure8.pdf. Readers who still have questions are encouraged to contact their PT program representatives, their accreditation organization or CMS state representative, as appropriate, or their state agency or CMS regional office: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/State_Agency_and_Regional_Office_CLIA_Contacts.html. What if CLIA doesn’t require PT for the analytes I test? As mentioned in this article, CLIA requires laboratories to demonstrate accuracy for all non-waived test methods at least twice per year if PT is not specifically required in Subpart I or PT is required, but the results for an event are not evaluated or scored. See Table 3 for a list of analytes specifically required in Subpart I. Of course, voluntary participation in a PT program could meet this requirement, but there are other ways to verify accuracy. One method that can be used is splitting some patient specimens with a colleague in a nearby laboratory who uses the same test system. Readers can refer to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute’s (CLSI) GP2914 for guidelines on ways that accuracy can be evaluated without participation in a formal PT program. What if my PT wasn’t graded? There are several possible reasons that PT is not graded, either for an individual laboratory or for all participants. In these cases, it is still necessary for the laboratory to do something to document that its test system is performing with acceptable accuracy. Failure to do so after an ungraded event may result in a deficiency citation. In this case, splitting patient specimens could demonstrate accuracy, and CLSI GP2914 provides additional ideas. I use more than one test system or method to test for a particular required analyte. Which one do I use for PT? CLIA requires that laboratories perform PT using the “primary” test system in use for patient testing during the PT event. There is a separate CLIA requirement for evaluating and defining the relationship between test results for the same test or analyte performed using different methods or test systems. |

APHL and CDC need your inputThe Association of Public Health Laboratories and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are surveying all U.S. laboratories that use PT to help them understand current PT practices in the United States. If your laboratory has not yet participated in the survey, your laboratory director or quality manager is encouraged to visit https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/aphl. |

The authors are health scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Laboratory Practice Standards Branch (LPSB) and work in support of the Clinical Laboratory Standards Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) regulatory program. An interagency agreement between CDC and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) establishes the scope of CLIA tasks which include: 1) analysis, research, and technical assistance; 2) implementation and monitoring of standards; 3) monitoring of proficiency testing (PT); 4) professional information and education; 5) management of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Advisory Committee; and 6) support for cytology activities. CDC LPSB is currently working with CMS to update CLIA regulations for PT.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions presented here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988, 42 U.S.C. 263a PL100-578 (1988).

- Laboratory Requirements, 42 C.F.R. Chapter IV, Part 493 (2003).

- Yost J. CLIA Update. Online presentation for Point of Care Coordinators. Sponsored by PointofCareNet. June 15, 2012. http://www.pointofcare.net/keypocc/061512_CLIA_Update.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2013.

- Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act of 1967, 42 U.S.C. 263a PL90-174 (1967).

- Jenny RW, Jackson KY. Proficiency test performance as a predictor of accuracy of routine patient testing for theophylline. Clin Chem. 1993;39(1):76-81.

- Reilly AA, McGinnis M, Stanton N, et al. Effectiveness of overt proficiency testing as a regulatory tool for assessing laboratory performance for blood lead. In: Krolak JM, O’Connor A, Thompson P, eds. Proceedings of 1995 Institute on Critical Issues in Health Laboratory Practice: Frontiers in Laboratory Practice Research. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1996:400. Abstract.

- Shahangian S. Proficiency testing in laboratory medicine. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122(1):15-30.

- Stull TM, Hearn TL, Hancock JS, Handsfield JH, Collins CL. Variation in proficiency testing performance by testing site. JAMA. 1998;279(6):463-467.

- Howerton D, Krolak JM, Manasterski A, Handsfield JH. Proficiency testing performance in U.S. laboratories. Results reported to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 1994 through 2006. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(5):751-758.

- Rej R. Accurate enzyme activity measurements. Two decades of development in the commutability of enzyme quality control materials. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993;117(4):352-364.

- Miller WG, Jones GRD, Horowitz GL, Weykamp C. Proficiency testing/external quality assessment: current challenges and future directions. Clin Chem. 2011;57(12):1670-1680.

- Miller WG, Myers GL, Ashwood ER, et al. Creatinine Measurement. State of the art in accuracy and interlaboratory harmonization. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129(3):297-304.

- Paxton A. Accuracy based surveys carve higher QA profile. CAP Today. Oct 2010. http://www.cap.org/apps/cap.portal?_nfpb=true&cntvwrPtlt_actionOverride=%2Fportlets%2FcontentViewer%2Fshow&_windowLabel=cntvwrPtlt&cntvwrPtlt%7BactionForm.contentReference%7D=cap_today%2F1010%2F1010e_accuracy_based_surveys.html&_state=maximized&_pageLabel=cntvwr). Accessed June 28, 2013.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Assessment of Laboratory Tests When Proficiency Testing Is Not Available; Approved Guideline—Second Edition. CLSI document GP29-A2. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2008.