Governments, diagnostic companies and providers respond to coronavirus outbreak

As the number of novel coronavirus cases continually increase throughout the world, laboratorians and hospitals need to ensure they are prepared to diagnose and treat infected patients.

When Chinese officials first released information about the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) on December 31, 2019, they described the illness as pneumonia with an unknown cause.

Just one week later, on January 7, 2020, Chinese officials identified a new coronavirus, sharing the genetic sequence publicly on January 12.

Despite relatively quick scientific legwork and discovery, the disease has spread rapidly throughout China, leading to a lockdown of at least 50 cities. Other countries have followed suit with travel restrictions, quarantines and other containment measures.

In late January, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency of international concern, designed to help countries coordinate resources, contain the spread of the disease, and minimize the impact on travel and the global economy.

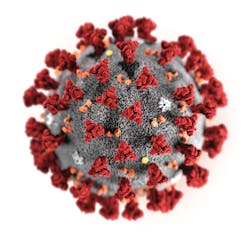

Like MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome) and SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), the virus is a betacoronavirus, which primarily originates in bats, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “The sequences from U.S. patients are similar to the one that China initially posted, suggesting a likely single, recent emergence of this virus from an animal reservoir,” CDC officials posted on the agency’s website.

Government agencies have responded by updating procedures for handling and testing potentially infectious specimens, while researchers and diagnostics companies have begun to develop tests and vaccines.

Meanwhile, laboratorians and hospital executives around the country brace themselves for the possibility that an infected patient will walk into their facility. To help them prepare, Medical Laboratory Observer (MLO) gathered pertinent information in this special report.

CDC Test Kits

In early February, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) filed by the CDC for a real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction test—the CDC 2019-nCoV Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel.

The Emergency Use Authorization expedites the usual regulatory process for the use of potentially life-saving medical or diagnostic products during a public health emergency. In this case, the FDA’s approval means that any CDC-qualified lab that is certified to perform high complexity tests can use the CDC’s diagnostic panel, the FDA said in an announcement.

The test detects the coronavirus from respiratory secretions, such as nasal or oral swabs. However, “negative results do not preclude 2019-nCoV infection and should not be used as the sole basis for treatment or other patient management decisions. Negative results must be combined with clinical observations, patient history and epidemiological information,” the FDA said in a statement announcing the decision to approve the CDC’s test.

“This will greatly enhance our national capacity to test for this virus,” National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD) Director Nancy Messonnier said during a press briefing in February. “In preparation for that approval, CDC has shipped the test to the International Reagent Resource, so that states and international partners can begin ordering the test for their use.”

The FDA is encouraging commercial enterprises to also use its Emergency Use Authorization process to shepherd any diagnostic tests they develop through the regulatory process.

Several organizations have already announced plans to develop tests.

One of those is altona Diagnostics, based in Hamburg, Germany, which is developing a molecular diagnostic assay for the detection of the new coronavirus by collaborating with major reference institutes for emerging diseases. The real-time RT-PCR-based assay will be designed for the qualitative detection of COVID-19 specific RNA in respiratory samples.

Co-Diagnostics, based in Salt Lake City, UT, is also developing a PCR screening test for the new coronavirus.

Meanwhile, IDbyDNA, based in San Francisco, CA, has announced that its Explify Respiratory test, a currently available laboratory developed test (LDT), can detect COVID-19.

Since the publication of the COVID-19 genome, IDbyDNA’s Salt Lake City lab has analyzed in-silico generated samples and validated computationally that Explify Respiratory test can detect the novel coronavirus, the company said in a news release.

In the meantime, Chinese laboratories are using existing products—such as mixes and enzymes from Meridian Bioscience in Nashville, TN—in molecular assays to diagnose infected patients.

During an earnings call in January, Roche said it developed tests for diagnosing the coronavirus for use by researchers, according to Kalorama Information, an Arlington, VA-based market research firm specializing in biotechnology, diagnostics, medical devices and pharmaceuticals.

CDC sample-collection procedures

The CDC has posted guidelines on its website about how labs should collect, handle and test specimens from people who might be infected with the novel coronavirus.

Generally, the CDC is “testing respiratory samples, but we are also testing blood, and we are currently working to expand the kind of diagnostics we can do, but the focus right now with the real-time PCR is respiratory specimens and sometimes blood,” Messonnier said at a press conference.

The CDC recommends collecting and testing multiple specimens from different sites, including both lower respiratory and upper respiratory tracts.

CDC officials want healthcare providers to notify their local or state health department about patients with fever and lower respiratory illness who might be infected with the novel coronavirus. Public health staff will then decide if patients meet the criteria for a patient under investigation (PUI) and coordinate work with the CDC’s Emergency Operations Center.

The CDC, which also has posted safety guidelines for handling specimens, says laboratory workers should wear personal protective equipment when handling potentially infectious specimens. The agency also says that any procedure with the potential to generate fine-particulate aerosols be performed in an enclosed and ventilated laboratory space, or class II biological safety cabinet, using physical containment devices.

Supply Chain Issues

Another concern for laboratory and hospital officials is access to the supplies they need to test and treat infected patients while also protecting employees.

Concerns about potential shortages of key supplies are driven, in part, by several recent developments.

The first issue is Cardinal Health’s recent recall of more than 9 million Level 3 gowns, which are used during surgical procedures or to provide barrier protection.

Cardinal Health decided to initiate the recall after learning in December 2019 that one of its FDA-approved suppliers in China, Siyang Holymed, had shifted production of some gowns to unapproved sites, with uncontrolled environments, meaning that Cardinal Health could not be sure that the gowns are sterile. Since then, Cardinal Health has terminated its relationship with Siyang Holymed.

To help bridge the supply gap, Cardinal Health is increasing production of similar products, sourcing alternative suppliers of gowns for its customers, and offering customers protective Level 4 gowns.

Cardinal Health is certainly not the only organization manufacturing medical products in China. As the outbreak spreads and China places more locations into lockdown, disruptions to the global medical supply chain are becoming increasingly worrisome.

Resilinc, a vendor of supply chain risk and resiliency software, believes there is a high risk of disruptions to the supply chain, based on global containment measures. Bindiya Vakil, founder and CEO of Resilinc, noted during a webinar presentation that businesses should expect supply chain disruptions for three to six months.

To help head off potential shortages of personal protective equipment, the World Health Organization (WHO) in January launched a private-public collaboration called “The Pandemic Supply Chain Network,” which is an effort to gather information about market capacity and risk assessment. It had hoped to complete the assessment by February.

Wuhan, the epicenter of the outbreak, is a manufacturing hub in China, including production of biotechnology products and the active ingredients, or APIs, used in pharmaceuticals, according to Resilinc. The city also is home to China’s largest inland port, which handles ocean-going ships, Resilinc adds.

Given the potential for supply chain issues, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response has been “assessing the level of preparedness” of pharmaceuticals and medical supplies within the Strategic National Stockpile, which can be used in the diagnosis and treatment of people infected with the novel coronavirus, HHS Secretary Alex Azar said in a news briefing in January.

Vakil recommends that organizations develop supply-chain preparedness plans based on likely scenarios, set clear triggers for action, and communicate information widely. The planning process also should include collaborating with suppliers, she added.

In a statement, Roche said it donated diagnostic tests, medical supplies and financial resources to the government, local health officials and hospitals in the Hubei Province.

Treatments and Vaccines

The WHO launched a clinical database platform, allowing countries to contribute clinical data in a standardized way, so global officials have the information they need to develop medical treatment protocols and public health measures.

As there is currently no known effective antiviral therapy for the novel coronavirus, the WHO also is conducting a systematic review of potential therapeutics and developing master clinical protocols to speed development of treatments globally.

For its part, the CDC uploaded the entire genome of the virus from the first and second cases reported in the United States in January.

The next steps will be the development of monoclonal antibody–based therapies for treating the virus and a Phase 1 clinical trial of a potential vaccine, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Director Anthony Fauci said at a press conference in January.

Working toward the goal of developing therapies, the HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) expanded an existing collaboration with Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Tarrytown, NY.

The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority within ASPR and Regeneron plan to develop multiple monoclonal antibodies that, individually or in combination, could be used to treat the coronavirus, HHS said in a press release.

Fauci also said that China was currently using both the antiviral remdesivir and the antiretroviral drug Kaletra (lopinavir and ritonavir) on a compassionate basis on some coronavirus patients. Both treatments, used against Ebola and HIV, respectively, are unproven against the novel coronavirus.

Meanwhile, commercial diagnostic companies and academic researchers have begun developing potential vaccines and treatments.

For example, Purdue University scientists Andrew Mesecar, Purdue’s Walther Professor in Cancer Structural Biology and head of the Department of Biochemistry, and Arun Ghosh, the Ian P. Rothwell Distinguished Professor of Chemistry, have been working to develop both oral medicines and vaccines to fight coronavirus. The molecules Mesecar and Ghosh have developed block two of the coronavirus enzymes (proteases), stopping the coronavirus from replicating.

Johnson & Johnson also has begun development of a vaccine for the novel coronavirus through its subsidiary, Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies, according to a press release.

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), based in Oslo, Norway, says it plans to coordinate the development of potential vaccines against the novel coronavirus. CEPI will coordinate vaccine development through partnerships with Inovio, based in Plymouth Meeting, PA; the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia; Moderna, based in Cambridge, MA; and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

CEPI, a partnership between public, private, philanthropic, and civil organizations, was founded in 2017 to develop vaccines against diseases such as novel coronavirus, Ebola, MARS, and others.

However, the coronavirus vaccines may not be developed quickly enough to help curtail the current spread of disease.

For example, Vas Narasimhan, CEO of Novartis, told CNBC in a recent interview that he expects development of a vaccine to take more than a year.

And as NIAID’s Fauci noted at a press conference, the U.S. never launched a Phase 2 trial with a vaccine for SARS because the outbreak dissipated before that step became necessary.

Nonetheless, Fauci said the United States is “proceeding as if we will have to deploy a vaccine” for the novel coronavirus.