Preparing point-of-care testing for the long journey

Driving a motor vehicle involves real-time inputs of road conditions and hazards. The same is true in healthcare: medical professionals need real-time inputs to guide decisions affecting patient outcomes. Point-of-care tests (POCT) are an option when providing this real-time insight, helping the clinician navigate the care pathway. Like driving, POCT requires skill and attention to avoid both “potholes and accidents” and losing time on the journey.

What is point-of-care testing (POCT)?

POCT refers to testing technologies and methods that provide test results at the place, or point, where care is delivered to the patient, versus in a separate laboratory. POCT is typically valued for providing timely test results for conditions requiring rapid treatment. As an example, in surgical pathology, frozen tissue sections are analyzed while patients are being operated on, to provide surgeons with crucial information about the type and extent of disease and to identify if surgical margins are free of disease. Other examples include arterial blood gases in the intensive care unit, providing near real-time critical information about respiratory and metabolic disorders and determining adequate hemoglobin levels in blood donors just prior to their donation. Many are familiar with home POCT applications, including urinary human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) as the first laboratory confirmation of pregnancy, glucose testing for people with diabetes, and rapid antigen testing for SARS-CoV-2 to diagnose COVID-19.

POCT can add value when utilized properly

A recent situation highlights the value of POCT. In response to the outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Uganda, some hospitals in the United States prepared intensive unit beds to accept incoming high-risk patients, especially those arriving at airports from international cities. This involved creating an extensive test menu using POCT that could be performed by either laboratory or intensive unit personnel in an area adjacent to the patient’s hospital room. This approach sought to limit the transfer of potentially infectious specimens to others on the healthcare team.

POCT options continue to expand, driven largely by the value of quick results allowing for timely medical decision making. POCT can also eliminate specimen transportation and storage issues, although confirmatory testing (of the same specimen) may often be warranted. Having near real-time POCT results allow the clinician and patient to discuss diagnoses or next steps in the moment. This capability can be critical in ensuring patients receive results and are adequately directed into care.

For instance, in the case of HIV testing, some patients offered anonymous testing never retrieved test results when testing was sent to a core or reference laboratory, including patients who had positive test results. This suggests that POCT would have provided immediately actionable results. Likewise, testing for sexually transmitted infections (e.g., chlamydia and gonorrhea) following treatment offerings may be more effective when results are nearly immediately available. Thus, POCT can provide timely test results while patients are engaged in their own health.

POCT – Screening versus confirmation

Most POCT tests are designed to screen for potential health risks. Sophisticated laboratory methods may follow to confirm a result. For instance, POCT urine tests may help screen for the presence of controlled drugs as part of a clinical drug monitoring program. But unlike confirmatory lab methods, these POCT devices have certain limitations that can affect clinical decision making. For instance, POCT devices may be unable to differentiate a prescribed opioid from non-prescribed fentanyl. COVID-19 is also a case in point. While rapid POCT antigen tests should be taken serially to confirm a result; molecular laboratory techniques are preferred to confirm a specimen as positive for SARS-COV-2. Laboratory professionals should understand the strengths and limitations of POCT and more sophisticated laboratory methods to ensure they complement, rather than duplicate, each other.

POCT versus in-laboratory testing: Challenges and opportunities

POCT assays are classified based on complexity. The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) defined waived testing as a simple test with low risk of patient harm resulting from incorrect results (presuming the test is used as described in the FDA labeling including robust quality system). That definition would hardly apply to the plethora of currently performed waived tests, which some POCT fall under. Some POCT results can have huge consequences on diagnoses and treatments especially if performed improperly. Laboratorians face continued challenges and opportunities in providing guidance on the value and limitations of POCT and support for its proper performance and oversight.

Those performing waived testing must follow manufacturers’ instructions. Moderately and highly complex tests are considered nonwaived tests and are subject to laboratory inspection and must comply with CLIA quality system standards including proficiency testing, semi-annual calibration/verification, quality control, personnel requirements, and documentation. Whereas hospital core laboratorians have largely mastered CLIA ’88 requirements, POCT remains more challenging to manage because it is performed in diverse settings outside of the clinical laboratory.

POCT’s areas of improvement

Many clinicians have outlined four main areas where POCT programs could seek to improve. These include:

- Coordination

- Connectivity

- Control

- Costs

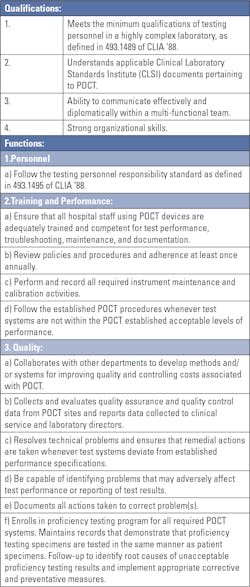

Coordination (See Table 1 for a sample coordinator job description.)

Successful hospital-based POCT programs typically have strong coordinators. Individuals assigned to this role must be qualified, have sufficient time to dedicate to the role, and have the authority to lead and control all aspects of testing. Many hospitals come up short when POCT coordinators lack the complete competency for this role.1

The POCT coordinator must also be part of a governance structure that includes nursing, the emergency department, the clinical laboratory, and other stakeholders of the institution to foster clear communication and an alignment of interests. As technology changes, the governance structure should provide a basis to decide which tests to perform, when to replace equipment, and how to address chronic issues.

Control

The ideal way to assure quality performance is to begin before the quality control materials are utilized; that is through training, analyzer maintenance, and documentation.2,3,4

POCT procedures should generally follow those in the core clinical laboratory. These procedures include storing all supplies at the right temperature — specifically, refrigerators and freezers must be monitored daily even when POCT is not performed. New lots of reagents or test strips must be evaluated prior to their use. A common approach is to check reagents and test strips upon delivery and run quality control samples at least monthly to check storage conditions and operator performance. Electronic instrument checks may be inadequate in establishing if the whole system functions properly. In POCT, some of the moderately complex testing may have both internal and external controls.

Recording only “in control” quality control results would be like a sports team recording only its wins. This is an unacceptable practice, hiding true assay performance. My observations are that many non-laboratorians do not understand quality control principles and procedures. Staff education on quality control principles and procedures must be key elements of training prior to initiating new and ongoing POCT analyzers.

Additionally, quality assurance plans are often lacking, even though such plans are vital to addressing ongoing method validation; monitoring operator and document management; and identifying and addressing issues like excessive test failures, expired supplies, or user errors. Shifts and drifts in patient test results are nearly impossible for individual users to identify, but aggregate data analysis can spotlight test faults.

POCT has the option to comply with Individualized Quality Control Plan (IQCP) (see CLIA’88 42 CFR 493.1256(d)), the alternative CLIA quality control option that provides for equivalent quality testing for 42 CFR 493.1250. IQCP has been incorporated in Appendix C of the State Operations Manual.5 IQCP is an all-inclusive approach to assuring quality. It includes many practices that a laboratory already uses to ensure quality testing beyond requiring that a certain number of quality control materials be tested at a designated frequency. IQCP applies to all nonwaived testing performed, including existing and new test systems.

Connectivity

Every test result must be appropriately documented to monitor quality control, proficiency testing, and patient care management.

Most POCT, even when appropriately enabled, is not connected to a hospital’s electronic health record (EHR) system. This makes each of the pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical POCT steps prone to human error, from scanning patient wristbands for correct identification to reporting of the right results to the right patient. Although the POCT result may be written in the patient chart, without the appropriate additional documentation, the test may not be billed properly, and therefore, the true costs of patient care cannot be understood.

Costs

The true costs of POCT includes instruments, reagents, quality control, proficiency testing, personnel (training, performance, troubleshooting, maintenance, documentation), and oversight.

Whereas some POCT cannot be replaced by standard clinical laboratory testing, some can, and comparisons can be made between the total cost of testing in each setting. The costs of staff for POCT are generally grossly underestimated, in part because of the distributed nature of POCT.

As we begin 2023, one of the most pressing challenges for many health systems is staffing, both within the laboratory and among nursing and other staff who perform POCT. Adequate training and support can be difficult with high staff turnover, staffing on late shifts, and temporary contract staff filling vacant positions. Maintaining technical assessments on all POCT assays for each staff member is an additional and often overlooked major undertaking.

Furthermore, quality control testing must be performed at least once daily on days when testing occurs. This can be costly for hospitals that use some tests infrequently. Lack of adherence not only jeopardizes the quality of testing but also potentially the laboratory license and certification if not reliant on a separate CLIA certificate.

Each test must undergo a full verification procedure at least once every six months and with reagent/strip lot changes. Some hospitals purchase small supply volumes to control inventory costs but do not recognize the added costs associated with frequent reagent/strip lot changes.

As hard as it may be, expired reagents must be discarded or returned, if allowed. Given some tests are performed infrequently in some locations, rotating reagents before expiration can avoid reagent/strip wastage. The POCT coordinator must develop procedures to audit reagent inventories to reduce reagent waste due to expiration.

Conclusion

To prepare POCT for the long journey, many EMR systems now include software that facilitates the documentation and control of users who are current with training and technical assessments. These management systems reduce, but do not eliminate, the need to dedicate the necessary resources to perform POCT correctly.

By careful planning, including identifying and developing a strong POCT coordinator, maintaining effective quality control procedures, enhancing electronic connectivity with the EHR system, and strictly tracking costs, hospital laboratories can provide a highly valuable and reliable service that improves medical diagnoses and healthcare management for patients.

References

- Gledhill TR, White SK, Lewis JE, Schmidt RL. A profile of point of care coordinators: Roles, responsibilities and attitudes, Lab Med, 2019;50(3):e50–e55. doi:10.1093/labmed/lmz011.

- Martin CL. Quality control issues in point of care testing. Clin Biochem Rev. 2008;29 Suppl 1:S79-82.

- Plebani M. Does POCT reduce the risk of error in laboratory testing? Clin Chim Acta. 2009; 404: 59-64.

- Venner AA, Beach LA, Shea JL, et al. Quality assurance practices for point of care testing programs: Recommendations by the Canadian society of clinical chemists point of care testing interest group. Clin Biochem. 2021;88:11-17. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2020.11.008.

- State Operations Manual. Cms.gov. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/som107ap_c_lab.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2022.

About the Author

Harvey W. Kaufman, MD

a board-certified pathologist, is Senior Medical Director at Quest Diagnostics. A 29-year veteran of Quest Diagnostics, Kaufman was an original and still active member of the Laboratory Working Group of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH (formerly the National Kidney Disease Education Program).