For point-of-care (POC) devices operating under the central laboratory license, the single biggest challenge for the adoption of POC testing is maintaining control, regulatory compliance, and training records for thousands of operators performing testing in anywhere from 30 to 50 locations within the hospital.1 This article will review the new Individual Quality Control Plan (IQCP) option slated to take effect on January 1, 2016, and present strategies and tools available to ease the burden of regulatory compliance and inspection preparedness.

CLIA certificates and POC complexity

In the United States all clinical testing, no matter where it is performed, is regulated by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA).2 In the CLIA-exempt states of Washington and New York, laboratories receive a state license, and must, at a minimum, comply with CLIA rules, in addition to their individual state’s regulations.

Testing sites may choose to have CLIA inspections, or to be accredited and inspected by organizations such as The Joint Commission (TJC, formerly JACHO), College of American Pathology (CAP), or the Commission on Office Laboratory Accreditation (COLA). The professional organizations inspect laboratory members using their own standards, which the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has reviewed and found to be at least equal to CLIA standards.2

The appropriate CLIA certificate identifying the complexity category of the testing performed must be obtained.2 Point-of-care testing (POCT) sites usually perform only waived and non-waived (moderately complex) testing.

It is important to note, however, that a waived POC test automatically becomes high complexity if it is used other than strictly according to the manufacturer’s directions.3 The majority of POCT done today is performed using instruments, or is migrating to instrument reading, to reduce subjectivity in result interpretation and transcription errors and to electronically capture required information.5

While CLIA does not have specific requirements for testing sites performing waived testing other than to follow manufacturers’ directions for use,2 other accrediting agencies may have specific standards for all categories of testing. The website of each accrediting organization should be consulted for updated requirements and preparedness checklists. Another resource, “The New Poor Lab’s Guide to the Regulations” by Sharon S. Ehrmeyer, PhD, is a practical, easy-to-read resource on regulatory compliance, inspection advice, and IQCP development.

The new IQCP option

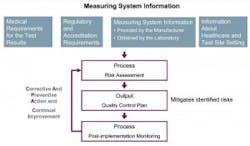

A quality control (QC) option for non-waived CLIA tests, IQCP replaces Equivalent Quality Control (EQC) options for QC beginning January 1, 2016, for meeting CMS §493.1256(d).3 Incorporating an IQCP is a voluntary option, and testing sites choosing not to implement IQCP will need to instead perform CLIA’s default QC policy which, in general, is two levels of external controls analyzed once per day for each and every test (Figure 1).3

Tools and resources

Historically, maintaining compliance requirements for POCT included operator management, device management, QC, and compliance reporting, among other critical requirements.4 Newer technology and enhanced products from manufacturers have helped POC testing sites overcome some of the compliance challenges.5 Examples include operator lockout to ensure authorized access to devices, QC lockout capabilities to enforce QC, and the integration and use of POC data management solutions that make it possible to connect hundreds of different devices in use.5

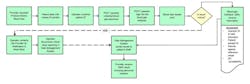

Today, device connectivity is available even for smaller devices, and informatics solutions provide additional functionality and workflow improvements.6 One example has eight core components linked by the data management system (Figure 2). It provides immediate oversight of the status of the POC program by identifying issues with devices, operators, samples, and results or compliance-related activities requiring attention.5

CMS mandates that “in-house” personnel use “in-house” information to develop an IQCP that is specific to their testing situation.3 One approach is to create a process flow map to document the testing process and identify risks.

An easy way to identify where potential and known risks exist is to color code the process steps. Most lab personnel find using the stop-light color scheme intuitive.

- Green: very little to no risk

- Yellow: moderate risk

- Red: known and frequent risk

The risk of patient harm if the process step fails is determined and documented. Applying the color to the flow diagram helps immediately focus attention on the process steps with the greatest risk to cause harm.

For example, in the acute care setting, blood gas analysis supports some of the most critical care decisions in surgery or intensive care. In a blood gas work flow, there is a one process step that has life or harm consequences—communicating a critical result to the provider.

Informatics can assist in managing this process and mapping a new risk-mitigated flow (Figure 3). By customizing POCT informatics, an operator prompt can be generated, requiring the operator to document the communication to the provider prior to the result being released for formal documentation. The patient’s results range can be customized to screen for critical results, validate the sample, and enforce critical results review and communication policies. The documentation is part of the result record, without the need to move into the emergency medical records (EMR) and ancillary informatics products to create the documentation.

The guidance and concepts for IQCP are a formal representation and compilation of many things testing sites already do to ensure quality results throughout all phases of testing. New informatics solutions are one tool to help facilitate the implementation of an IQCP, improve clinical workflows, and satisfy compliance requirements to aid testing sites with inspection preparedness.

References

- Nichols JH. Point of care testing. Clin Lab Med. 2007;4:893Y908.

- Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA): how to obtain a CLIA certificate. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/Downloads/HowObtainCLIACertificate.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2015.

- Ehrmeyer S. The New Poor Lab’s Guide to the Regulations (CLIA, The Joint Commission, CAP & COLA) 2015 Westgard QC, Inc.

- Gregory K, Lewandrowski K. Management of a point-of-care testing program. Clin Lab Med. 2009;3:443Y448.

- Gramz J, Koerte P, Stein D. Managing the challenges in point-of-care testing, an ecosystem approach. Point of Care. 2013;12(2):76-79.

- Jones RG, Johnson OA, Hawker MD. Informatics in point-of-care testing. In: Price CP, St John A, Kricka LL, eds. Point-of-Care Testing: Needs, Opportunities, and Innovation. Washington, DC: AACC Press; 2010:287Y309.