How labs can help clinicians diagnose myocardial infarctions in women

For a printable version of the June CE Story and test go HERE or to take test online go HERE. For more information, visit the Continuing Education tab.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Upon completion of this article, the reader will be able to:

1. Describe the reasons why clinicians misdiagnose myocardial infarctions (MI), including the role of implicit gender bias

2. Describe the differences between men and women with regards to heart attacks

3. Describe how a high-sensitivity troponin assay can improve MI diagnoses in women

4. Recall what laboratories can do to transition to a high-sensitivity troponin assay

Despite these high numbers, doctors may be more likely to dismiss heart attack symptoms as not being heart-related in women younger than age 55.3 In fact, regardless of age, women die of a heart attack more often than men because clinicians may not recognize heart disease in women.4 Studies have shown that women are not only less likely to receive blood clot prophylaxis,5 but may also receive less intensive treatment for a heart attack.6 Women older than 50 who are critically ill are at risk of not receiving lifesaving interventions.

Several biomarkers are influenced by sex, including high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn), with men reportedly presenting higher concentrations than women. Accordingly, the need for sex-specific reference values has been pointed out by several authors,7 supporting the idea that sex differences should be taken into account when approaching laboratory tests.

A prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom found that a high-sensitivity troponin assay with sex-specific diagnostic thresholds may double the diagnosis of myocardial infarction in women and identify those at high risk of reinfarction and death,8 because women have lower cTn values, which a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assay can detect.

Women in pain are ignored by physicians

The word hysteria originates from the Greek word for “uterus,” and still holds a pervasive belief in the medical community when a woman has a health concern. Female hysteria was once a common medical diagnosis for women, applied whenever women displayed “inappropriate” emotions, such as anxiety, anger, and even sexual desire. For centuries, it was believed that the uterus itself was the cause of a woman’s “hysterical” symptoms.9 There is more than anecdotal evidence to back up these gender discrepancies – statistics also show that women are more likely to be told their pain is “psychosomatic” than men are.10 This implicit gender bias in medicine leads to poor outcomes for women.

The data is concerning. Women in pain are more likely than men to receive prescriptions for sedatives rather than pain medication.11 Women wait an average of 65 minutes before receiving an analgesic for acute abdominal pain in the ER in the United States, while men wait for only 49 minutes.12 The undertreatment of pain in women may also be due to the widely held, but false notion, that women have higher pain tolerance than men.13 In addition, one in five women believe that a healthcare provider has ignored their symptoms and feel they are ignored within the healthcare system, blocking them from receiving the care they desperately need. For example, women who receive coronary bypass surgery are only half as likely to be prescribed painkillers, compared to men who receive the same procedure.14

One alarming finding is that women are seven times more likely than men to be misdiagnosed and discharged in the middle of having a heart attack, because the symptoms are missed.15

In general, women with suspected acute coronary syndrome are less likely to undergo a complete medical workup or receive treatment than men, and women consistently have worse outcomes.16

Misunderstanding a woman’s heart attack

There is a perception that heart disease is a man’s domain, and women are more likely to die of breast cancer. Although women tend to develop heart disease a decade later than men, they fare worse after a heart attack, in large part due to the failure to identify heart attack symptoms. In fact, 35% of heart attacks in women are believed to go unnoticed or unreported.17

Women exhibit different symptoms of a heart attack than men and may be told they are suffering from reflux or anxiety.

Women are underrepresented in clinical trials for heart failure, coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndrome, but are proportionately or overrepresented in trials for hypertension, atrial fibrillation and pulmonary arterial hypertension, when compared to incidence or prevalence of women within each disease population.18 This may well be why women are missed in typical cardiac workups: if they weren’t in the trials, then their common symptoms won’t be represented in the clinical care pathways.

To summarize, here are the key reasons why women fare more poorly when it comes to heart attack mortality:

- Women have different heart attack symptoms than men, and clinicians and women often miss them.

- Clinicians have implicit gender bias and dismiss female symptoms as non-cardiac.

- Women were underrepresented in traditional clinical trials.

Women and men respond differently to a cardiac incident

When we think heart attack, we imagine a man clutching his chest in agony, five minutes prior having complained about pain in his left arm. Even though chest pain is still the most common sign of a heart attack for most women, studies have shown that women are more likely than men to have symptoms other than chest pain or discomfort when experiencing a heart attack or other form of acute coronary syndrome.19

Even though heart disease is the number one killer of women in the United States, women often chalk up their symptoms to less life-threatening conditions, like acid reflux, the flu or normal aging. This dismissal of symptoms means that women wait longer before going to the hospital, which worsens their condition and opens the door for a deadly condition known as cardiogenic shock.20

In the context of cardiovascular disease, a significant relationship between increasing age and stroke risk in women, compared to men, is most evident at the age of 65 years or older.21

Here are some key differences between men and women when it comes to heart attacks:22

- Women are more likely to have cardiac chest pain syndromes not directly associated with obstruction of the large epicardial coronary vessels as men do.

- On average, women are almost a decade older than men at the time of their initial MI.

- Women are less likely to be referred for coronary angiography than men.

- Women are less likely to receive fibrinolytic therapy, a percutaneous coronary intervention, or a coronary artery bypass surgery.

- In-hospital and long-term mortality after MI is higher in women than in men.

- In younger women with MI, short- and long-term mortality may be worse than mortality in younger men, even after adjusting for several prognostic characteristics.

Understanding a woman’s heart attack

As noted, women often exhibit different symptoms than men. Women tend to have symptoms more often when resting, or even when asleep, than men. Stress can play a role in triggering heart attack symptoms in women.23

Because women do not always recognize their symptoms as those of a heart attack, they tend to show up in emergency rooms after heart damage has occurred. Also, because their symptoms often differ from men’s, women might be diagnosed less often with heart disease than men.24

The American Heart Association25 suggests that if women have any of the below signs, they should call 9-1-1 and get to a hospital right away:

- Uncomfortable pressure, squeezing, fullness or pain in the center of their chest, especially if it lasts more than a few minutes, or goes away and comes back

- Pain or discomfort in one or both arms, the back, neck, jaw or stomach

- Shortness of breath with or without chest discomfort

- Other signs, such as breaking out in a cold sweat, nausea or light-headedness

As with men, women’s most common heart attack symptom is chest pain or discomfort, but women are somewhat more likely than men to experience some of the other common symptoms, particularly shortness of breath, nausea/vomiting and back or jaw pain.

The sooner the patient gets to an emergency room, the sooner treatment can begin to reduce the amount of damage to the heart muscle. At the hospital, healthcare professionals can run tests to find out if a heart attack is happening and decide the best treatment.26

Improving care for female patients

To offer customized patient care, it is clinically important to determine myocardial injury (which is variable among reagents, age, sex, or race), which can be achieved by defining the 99th percentile upper reference limits (URL) of cardiac troponin I (cTnI).27 An important finding in studies has been that the 99th percentile of hs-cTn assays in healthy individuals is significantly lower in women, as compared to men, in part, related to the smaller size of women’s hearts.28 Sex-specific 99th percentiles are recommended for defining abnormal cTnI concentrations, especially for hs-cTn assays; otherwise, acute myocardial infarction may be underdiagnosed in women.29 According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the sex‐specific cutoffs in the United States for women is 13.6 ng/L for women, and is 19.8 ng/L for men, or a single cutoff of 18.1 ng/L, with recommended use in conjunction with other signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of MI.30

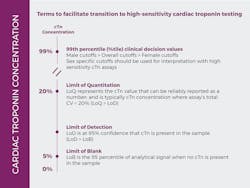

Adoption of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) I or T assays has taken off around the world, including the United States. With the transition to more sensitive troponin assays comes the need to develop a consensus regarding aspects that medical systems should consider before the implementation of these assays, which differ considerably from “conventional” cardiac troponin (cTn) methods. Additionally, even within the category of hs-cTnI or T assays, there will be variability in cutoff values, sensitivity, and specificity, as well as in the way in which these tests are interpreted.31

Some key questions that laboratorians must answer as they transition to hs-cTn:

- Is the lab ready to provide the necessary analytical education?

- Has an assay been selected?

- Was assay performance acceptable in the local clinical lab?

- Which 99th percentile cutoff(s) will be used?

- Is the lab able to process samples within a reasonable time frame?

- Is the reporting of results integrated well with the electronic health record?

Besides the lab, the ED must also prepare itself by educating clinicians about the basic concepts of how high-sensitivity troponin differs from the previous troponin methods and understand the differential diagnosis of an abnormal hs-cTn concentration

There are many benefits of implementing high-sensitivity troponin to diagnose MI. Among patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome, hsTnI may help rule out patients sooner in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or early diagnosis of AMI, 32 and also reclassify some unstable angina pectoris diagnoses (UAP) to myocardial infarction (MI).33

The hsTnI assay allows more accurate and earlier detection of MI, enabling physicians to improve patient care and outcomes.34 More accurate diagnosis of AMI can lead to timelier and more efficient triage, more accurate therapeutic and management approaches, reduced time in the emergency department, reduced healthcare costs, reduced disease complications, and improved clinical outcomes.35

More importantly, a high-sensitivity troponin assay can reduce implicit gender bias, as clinicians will have sex-based data to aid their diagnosis, instead of dismissing a woman’s heart attack symptoms as anxiety. This does require a change in clinicians’ behavior, ensuring they order hsTnI for women who come to their emergency room with symptoms that do not look like a typical heart attack in a man. Time is muscle, and every minute counts. Suspect an MI in women early, and you may well save a life.

References

- Women and Heart Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/women.htm. Published January 31, 2020. Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Harvard Health Publishing. The heart attack gender gap. Harvard.edu. https://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/the-heart-attack-gender-gap Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Harvard Health Publishing. Clinicians sometimes misread heart attack symptoms in women. Harvard.edu. https://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/clinicians-sometimes-misread-heart-attack-symptoms-in-women Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Time: women die from heart attacks more often than men. Here’s why – and what doctors are doing about it. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Published April 5, 2019. https://www.cedars-sinai.org/newsroom/time-women-die-from-heart-attacks-more-often-than-men-heres-why--and-what-doctors-are-doing-about-it/ Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Pietropaoli AP, Glance LG, Oakes D, Fisher SG. Gender differences in mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Gend Med. 2010;7(5):422-437. doi:10.1016/j.genm.2010.09.005.

- Vaccarino V, Rathore SS, Wenger NK, et al. Sex and racial differences in the management of acute myocardial infarction, 1994 through 2002. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(7):671-682. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa032214.

- Romiti GF, Cangemi R, Toriello F, et al. Sex-specific cut-offs for high-sensitivity cardiac troponin: Is less more? Cardiovasc Ther. 2019;2019:9546931. doi:10.1155/2019/9546931.

- Shah ASV, Griffiths M, Lee KK, et al. High sensitivity cardiac troponin and the under-diagnosis of myocardial infarction in women: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:g7873. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7873.

- Gaslighting in women’s health: No it’s not just in your head. Northwell Health. https://www.northwell.edu/katz-institute-for-womens-health/articles/gaslighting-in-womens-health Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Lindy. Doctors don’t always take women seriously, and it’s an issue. Fair Care Project. Published January 7, 2020. https://medium.com/faircareproject/doctors-dont-always-take-women-seriously-and-it-s-an-issue-8085d40c7c10 Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Calderone KL. The influence of gender on the frequency of pain and sedative medication administered to postoperative patients. Sex Roles. 1990;23(11-12):713-725. doi: 10.1007/bf00289259.

- Fassler J. How doctors take women’s pain less seriously. The Atlantic. Published October 15, 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/10/emergency-room-wait-times-sexism/410515/ Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Smith S. Who’s Really Hurting? Virtual Mentor. 2002;4(8):virtualmentor.2002.4.8.jdsc1-0208. Published 2002 Aug 1. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2002.4.8.jdsc1-0208.

- Fields I. Gender bias in health care is playing a dangerous role in COVID-19 care. Ms. Published October 15, 2020. https://msmagazine.com/2020/10/15/gender-bias-health-care-covid-19 Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Nabel EG. Coronary heart disease in women – an ounce of prevention. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(8):572-574. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008243430809.

- Shah ASV, Ferry AV, Mills NL. Cardiac biomarkers and the diagnosis of myocardial infarction in women. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2017;19(5). doi:10.1007/s11886-017-0839-9.

- Giardina EG. Heart disease in women. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2000;45(6):350-357.

- Scott PE, Unger EF, Jenkins MR, et al. Participation of women in clinical trials supporting FDA approval of cardiovascular drugs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(18):1960-1969. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.070.

- Heart attack symptoms in women — are they different? National Institutes of Health. Published September 30, 2015. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/heart-attack-symptoms-women-are-they-different Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Women get worse care for heart attack. Webmd.com. https://www.webmd.com/heart-disease/news/20200929/women-get-worse-care-for-heart-attack Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Marzona I, Proietti M, Farcomeni A, et al. Sex differences in stroke and major adverse clinical events in patients with atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 993,600 patients. Int J Cardiol. 2018;269:182-191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.07.044.

- Canto JG, Goldberg RJ, Hand MM, et al. Symptom presentation of women with acute coronary syndromes: myth vs reality: Myth vs reality. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(22):2405-2413. doi. 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2405

- Heart disease in women: Understand symptoms and risk factors. Mayoclinic.org. Published October 4, 2019. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/in-depth/heart-disease/art-20046167 Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Szabla M. Women and heart disease. Mayo Clinic. Published February 16, 2021. https://www.cpaawa.org/2021/02/16/women-and-heart-disease-blog-post/. Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Heart attack symptoms in women. J Okla State Med Assoc. 2012;105(2):66-67.

- Heart attack symptoms, risk, and recovery. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/heart_attack.htm Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Kim S, Yoo SJ, Kim J. Evaluation of the new Beckman Coulter Access hsTnI: 99th percentile upper reference limits according to age and sex in the Korean population. Clin Biochem. 2020;79:48-53. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2020.02.005.

- Giannitsis E, Kurz K, Hallermayer K, Jarausch J, Jaffe AS, Katus HA. Analytical validation of a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay. Clin Chem. 2010;56(2):254-261. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.132654.

- Clerico A, Zaninotto M, Ripoli A, et al. The 99th percentile of reference population for cTnI and cTnT assay: methodology, pathophysiology and clinical implications. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2017;55(11):1634-1651. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2016-0933.

- Food and Drug Administration. 510(k) Substantial equivalence determination: determination. Assay only template. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/reviews/K172783.pdf Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Januzzi JL Jr, Mahler SA, Christenson RH, et al. Recommendations for institutions transitioning to high-sensitivity troponin testing: JACC scientific Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(9):1059-1077. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.046.

- Keller T, Zeller T, Ojeda F, et al. Serial changes in highly sensitive troponin I assay and early diagnosis of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2011;306(24):2684-2693. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1896.

- Januzzi JL, Sharma U, Zakroysky P, et al. Sensitive troponin assays in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome: Results from the multicenter rule out myocardial infarction using computer assisted tomography II trial. Am Heart J. 2015;169(4):572-8.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.12.023.

- Giannitsis E, Katus HA. Troponins: established and novel indications in the management of cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2018;104(20):1714-1722. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311387.

- Christenson RH, Peacock WF, Apple FS, et al. Trial design for assessing analytical and clinical performance of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I assays in the United States: The HIGH-US study. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2019;14(100337):100337. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100337.

About the Author

Shamiram Feinglass MD, MPH

is the Vice President, Global Government and Medical Affairs at Beckman Coulter. In this position, she leads Global Medical, Government, Reimbursement, and Clinical Affairs for Life Sciences and Diagnostics and drives talent diversity in every environment in which she works or leads. Feinglass was formerly the Vice President for Global Medical and Regulatory Affairs at Zimmer, Inc.

Lindsay Sun, MD

is Senior Scientific Affairs Manager for Beckman Coulter.

![Figure 1: Heart Disease in Women Source: joekeenan. American heart month: Heart disease in women [infographic]. Vitaloptions.org. Published March 9, 2020. Accessed March 24, 2021. https://www.vitaloptions.org/american-heart-month-heart-disease-in-women-infographic/ Figure 1: Heart Disease in Women Source: joekeenan. American heart month: Heart disease in women [infographic]. Vitaloptions.org. Published March 9, 2020. Accessed March 24, 2021. https://www.vitaloptions.org/american-heart-month-heart-disease-in-women-infographic/](https://img.mlo-online.com/files/base/ebm/mlo/image/2021/05/pg1_hsTnl_Women_MLO_Graphics_edit.609c2859c8040.png?auto=format,compress&fit=max&q=45?w=250&width=250)