What is my patient’s volume status? Leveraging plasma volume estimation to guide clinical decisions in and beyond the ICU

A 78-year-old female with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) presented to the emergency department (ED) with a productive cough and shortness of breath. On examination she appeared well, she had scattered wheezing bilaterally but otherwise had a normal physical exam. She had a tympanic temperature of 39 degrees C, with normal blood pressure and pulse. Laboratory examination revealed a mild leukocytosis of 11.8 cells/microliter, an estimated plasma volume (ePV)—a figure calculated from the hemoglobin and hematocrit-- of 6.8 dL/g, and a normal lactate. Chest x-ray revealed mild bilateral patchy infiltrates. Her oxygen saturation on 2L nasal cannula was 91%. Her calculated Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score was 1, predicting low mortality.

She was admitted to the floor and placed on IV antibiotics for presumed pneumonia and bronchodilators for her COPD. Approximately 4 hours after admission she was noted to have a BP of 85/40, with a pulse of 110, and a respiratory rate of 30. She was transferred to the ICU where she was intubated and had an arterial line placed. Initial arterial blood gas revealed a pH of 7.29, pO2 of 68, pCO2 of 55, and an HCO3 of 19. Lactate level was 2.8 mmol/L. Her white blood cell count was slightly higher at 12.5 cells/microliter, and her ePV was elevated further to 7.4. Given potential fluid overload and hypotension she was started on vasopressors rather than being fluid resuscitated. Her condition stabilized, sputum and blood cultures grew Streptococcus pneumoniae, and her antibiotic regimen was adjusted accordingly. She remained on mechanical ventilation for 3 days and in the ICU for 5 days, eventually being discharged to a rehabilitation facility after a 10-day hospital stay.

This case highlights the ability of the ePV to make the diagnosis of sepsis in patients who look otherwise well. Based on this patient’s physical examination and laboratory findings, and a low SOFA score, she appeared to have an uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia. However, the elevated ePV on admission could have been an indicator that her condition was more serious than it initially appeared. If it was, and the patient was treated more aggressively on admission (e.g., admission to the ICU, diuresis, early pressor use, etc.), it’s possible that her outcome would have been improved.

We will discuss the utility of using ePV as a prognostic indicator for various disease states further.

Assessment of patients’ fluid status

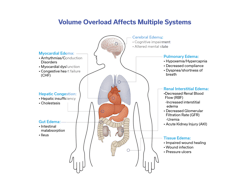

Assessment of a patient’s volume status is a task that clinicians do daily in managing hospitalized patients as it affects multiple systems of the body (Figure 1). In critically ill patients, it may be done more frequently, even hourly. It aids in determining end-organ perfusion and helps caregivers decide on interventions such as the need for intravenous fluids, diuresis, ventilator settings, blood pressure management, and kidney function, among others. The precise determination of a patient’s fluid status is something that is not clearly defined and is generally made by the clinician using a variety of modalities: physical examination, vital signs, laboratory and radiologic findings, and sometimes invasive testing or complex technological devices (Figure 2). Despite these many ways of determining a patient’s volume status, there is no universally accepted standard for what represents the true value. Many of these methods give conflicting results, and even experienced clinicians can disagree on what the true plasma volume in any given patient is. This can directly impact patient care—for example, does a septic patient with a low blood pressure need vasopressors or a fluid bolus? Does a patient with COPD who is difficult to wean have fluid overload? When do you stop diuresis in a heart failure patient? Answers to these questions and many others rely on accurate assessment of a patient’s fluid status, specifically their intravascular fluid status.

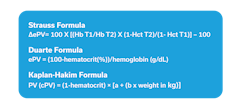

The concept of estimated plasma volume (ePV) was developed in the 1950’s when Maurice Strauss gave healthy individuals a fluid bolus and measured their hemoglobin and hematocrit (H&H) before and after.1 He devised a formula to calculate the change in plasma volume (ΔPV) based on the difference in H&H. This formula has since been modified by Duarte to reflect a single instance of ePV,2 and by Kaplan to incorporate weight and sex3 usually referred to as plasma volume status (PVS) or Kaplan-Hakim PVS/ePV (Figure 3). It is worth noting that since the variables in the formulas rely on both hemoglobin and hematocrit, it is important that both parameters are measured and not calculated. Many point-of-care devices that report H&H will measure only one and calculate the other, which increases the bias introduced when calculating ePV.

These formulas remained relatively unnoticed for decades until 2015, when a group of cardiologists in Nancy, France rediscovered them and found that they had prognostic value in heart failure patients.2 Since that time, the formulae have been found to be helpful for determining prognosis in many wide-ranging conditions:

- Myocardial infarction (MI)

- Aortic and mitral valve replacement

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Sepsis

- Overall mortality

- Cancer mortality

- Kidney transplant

- Pancreatitis

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Aortic aneurysm repair

- Peripheral vascular surgery

- COVID-19

These conditions have all been studied retrospectively, and currently prospective studies are underway to determine the usefulness of ePV for clinical decision making in real time. Two areas where this would be most helpful are in patients with heart failure and those with respiratory distress and/or sepsis. These are conditions that account for significant morbidity, mortality, and cost of care despite years-long global efforts to reduce their impact.

Role of estimated plasma volume in heart failure

It makes intuitive sense that ePV would be a good diagnostic marker for heart failure—a condition of congestion and fluid overload, treated by diuresis and other strategies for decongestion. As noted above, this was utilized by Duarte and colleagues in 2015 to retrospectively analyze patients enrolled in the EPHESUS study (Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study) and found it to have prognostic value.2 The EPHESUS study enrolled patients who developed HF after MI and had an ejection fraction (EF) of 40% or less (heart failure with reduced ejection fraction or HFrEF). Endpoints included cardiovascular death or hospitalization for HF between 1–3 months after myocardial infarction (MI). Assessments were made at enrollment, and at one month, three months, and then every three months after enrollment. Increasing ∆ePVS between enrollment and one month and increased ePVS at enrollment and at 3 months were associated with cardiovascular (CV) events, with ∆ePVS and ePVS at 1 month being retained in multivariate analysis. Surprisingly, ∆ePVS did not correlate with weight, and patients who lost weight during the time interval had an increase in CV events if ∆ePVS increased. This group as well as most HF researchers favor the Strauss formula over the Hakim formula because of the difficulty in estimating the dry body weight in this patient population. Since that time, there have been numerous studies confirming that ePV and ∆ePVS can provide some prognostic information.

Bilchick and colleagues used the Strauss formula to evaluate patients enrolled in the Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness trial (ESCAPE). They calculated the ePV on admission and discharge and found that patients who had an increase in ePV or no change had a higher mortality at six months than those whose ePV decreased during admission.4

A cohort of 449 patients in Taiwan with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) were evaluated using the Strauss formula to calculate ePV and ∆ePV. Higher baseline ePV and higher ∆ePV were predictive of increased mortality and hospitalization for HF.5

Chen and associates evaluated 253 patients who were admitted to Putian Hospital in China with HF. Patients had echocardiographic measurement of left atrial diameter (LAD), as well as NT-proBNP and ePV calculated using the Strauss formula, with outcomes of HF readmission and cardiac death evaluated. On regression analysis, ePV (OR = 2.061, 95% CI 1.322∼3.214, p = 0.001), was the strongest predictor of outcomes, with LAD (OR = 1.054, 95% CI 1.012∼1.098, p = 0.011), and NT-proBNP (OR = 1.006, 95% CI 1.003∼1.010, P = 0.036) weaker predictors.6 In addition, increasing ePV increased the risk of cardiogenic mortality.

The value of the Strauss-derived ePV was also affirmed by Wu and colleagues from Beijing, China. They evaluated 195 patients with advanced HF using right heart catheterization to measure hemodynamics. The sum of right atrial pressure (RAP) and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure (PAWP) > 30 mmHg was considered hemodynamic congestion. Patients with an ePV greater than 4.08 dL/g were more likely to have clinical signs of congestion (e.g., rales) and had higher mortality regardless of their catheterization pressures.7 This led the authors to advocate using ePV as an independent prognostic marker for patients with HF.

While there is hardly consensus on the place of ePV in clinical decision making, most authors agree that in the absence of more robust measurements, ePV values and trends are important surrogate markers for volume status and predictors of worse outcomes in patients with heart failure. There are still opportunities to further refine the value of ePV in these patients: can use of ePV in the outpatient setting help reduce readmissions, can serial, prospective ePV measurement guide clinical decision making, are there heart failure subgroups which will benefit more from ePV measurement? Since many interventions in cardiology and heart failure in particular are costly and/or invasive, it would seem logical that an inexpensive, non-invasive metric that is easy to obtain would be important in widely varying clinical settings.

Role of estimated plasma volume in respiratory care

Fluid overload impairs lung mechanics, worsens gas exchange, and prolongs ventilatory dependence in syndromes such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), COVID-19 ARDS, and acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD).

Intravascular volume expansion increases hydrostatic pressure and promotes fluid transudation into the pulmonary interstitium—an especially harmful process in ARDS and sepsis, where endothelial injury and glycocalyx disruption amplify capillary leak. In COPD exacerbations, elevated plasma volume can worsen expiratory flow limitation, dynamic hyperinflation, and right ventricular strain. ePV therefore captures a relevant hemodynamic signal at the intersection of cardiovascular congestion and respiratory failure.

One of the largest analyses of volume markers in ARDS comes from Niedermeyer et al., who evaluated 3,165 participants enrolled in four randomized trials of ARDS therapy.8 Using the Kaplan–Hakim method to calculate plasma volume status (PVS), the authors found that 68% of ARDS patients had plasma volume expansion, and PVS greater than the median value of 5.9 was independently associated with a 38% greater risk for mortality (HR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.20-1.59; p<0.001), fewer ventilator-free days (18 vs 19d; p=0.0026) and ICU-free days (15 vs 17d; p<0.001). These findings align with the landmark FACTT trial,9 which demonstrated that conservative fluid management improves oxygenation and reduces ventilation duration in ARDS. Niedermeyer et al. also found that each interquartile range increase in PVS was associated with greater mortality (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.13-1.36; p<0.001) indicating a linear relationship and further emphasizing the importance of PVS as a risk marker in ARDS and potential treatment metric for fluid restrictive management and early deresuscitation.

COVID-19 ARDS amplifies vascular injury, thrombosis, and endothelial leak, rendering patients particularly sensitive to fluid overload. In a multicenter cohort of 1,298 COVID-ARDS patients, Balasubramanian et al. found that higher admission PVS—calculated within 24 hours of hospitalization—was independently associated with 90-day mortality (HR, 1.015; 95% CI, 1.005-1.025; p=0.002).10 This association persisted after adjustment for age, comorbidities, BMI, vaccination status, SOFA score, renal function, and inflammatory markers. Moreover, survivors had lower PVS values and a more negative cumulative fluid balance throughout hospitalization. These findings support an expanded role for ePVS as a triage and treatment tool in COVID-19 ARDS, where even modest excess intravascular volume may worsen lung compliance and prolong invasive ventilation.

In a large ICU cohort of 2,773 AECOPD patients, Guo and Zhang compared two ePVS formulas and found that Kaplan–Hakim ePV was strongly associated with in-hospital mortality after multivariable adjustment.11 Patients in the highest ePV category had more than a 50% increased risk of death (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.05-2.24; p=0.0029). Subgroup analyses in this study showed that the prognostic signal was especially strong in those without sepsis (HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.11-2.85; p=0.017) or heart failure (HR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.34-3.56; p=0.002)—suggesting that ePV captures hemodynamic stress not explained by traditional diagnoses. Given that fluid overload exacerbates air trapping and can precipitate NIV failure, ePV may help respiratory therapists and intensivists identify patients at risk of early decompensation or difficult weaning.

Although prospective and interventional data are still lacking, the current evidence suggests that ePV is a robust, low-cost, and highly scalable biomarker with significant utility in respiratory care. It captures a clinically meaningful dimension of intravascular congestion that complements, rather than replaces, existing assessments. As fluid stewardship becomes increasingly central to ARDS and COPD management, ePV stands out as a promising tool to enhance precision in the care of patients with acute respiratory failure.

References

- Strauss MB, Davis RK, Rosenbaum JD, Rossmeisl EC. Water diuresis produced during recumbency by the intravenous infusion of isotonic saline solution. J Clin Invest. 1951;30(8):862-8. doi:10.1172/JCI102501.

- Duarte K, Monnez JM, Albuisson E, et al. Prognostic value of estimated plasma volume in heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(11):886-93. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2015.06.014.

- Kaplan AA. A simple and accurate method for prescribing plasma exchange. ASAIO Trans. 1990;36(3):M597-9.

- Bilchick KC, Chishinga N, Parker AM, et al. Plasma volume and renal function predict six-month survival after hospitalization for acute decompensated heart failure. Cardiorenal Med. 2017;8(1):61-70. doi:10.1159/000481149.

- Huang CY, Lin TT, Wu YF, Chiang FT, Wu CK. Long-term prognostic value of estimated plasma volume in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):14369. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-50427-2.

- Chen X, Lin G, Dai C, Xu K. Effect of estimated plasma volume status and left atrial diameter on prognosis of patients with acute heart failure. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1069864. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2023.1069864.

- Wu Y, Tian P, Liang L, et al. Estimated plasma volume status adds prognostic value to hemodynamic parameters in advanced heart failure. Intern Emerg Med. 2023;18(8):2281-2291. doi:10.1007/s11739-023-03422-5.

- Niedermeyer SE, Stephens RS, Kim BS, Metkus TS. Calculated plasma volume status is associated with mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Explor. 2021;3(9):e0534. doi:10.1097/CCE.0000000000000534.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network; Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2564-75. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa062200.

- Balasubramanian P, Isha S, Hanson AJ, et al. Association of plasma volume status with outcomes in hospitalized Covid-19 ARDS patients: A retrospective multicenter observational study. J Crit Care. 2023;78:154378. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2023.154378.

- Guo X, Zhang L. Estimated plasma volume status and the risk of in-hospital mortality among patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in intensive care unit: Retrospective cohort study from the eICU Collaborative Research Database. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2025;20:611-621. doi:10.2147/COPD.S484726.

About the Author

Martin Ekiti, MD, MPHc

is the Medical Director, Medical and Scientific Affairs at Nova Biomedical, a Family Physician, and MPH Candidate at the Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Matt Davis, BS, RRT

is an Account Executive at Nova Biomedical. Previously, he was Education Coordinator, University of Maryland Medical Center and the previous President of the MD/DC Society for Respiratory Care.

Dennis Begos, MD, FACS

is a board-certified physician and surgeon with over 20 years’ experience in clinical medicine, medical education, and administration. Most recently, he was Senior Medical Director at Nova Biomedical.