Importance of hemoglobin A1c testing for diabetes diagnosis and management post-COVID-19 infection

How does hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) testing support diabetes care?

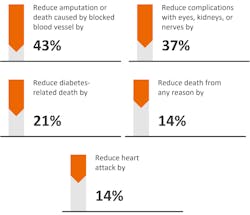

The number of people affected by diabetes is expected to grow and may be further increased by the COVID-19 pandemic, as people <18 years of age were shown to be 2.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes following infection with COVID-19 compared to those without infection.1 Diabetes mellitus, a group of metabolic disorders affecting glucose metabolism, is derived from the Greek word diabetes (to pass through) and the Latin word mellitus (sweet). Approximately one-third of Americans are prediabetic (defined by an HbA1c between 5.7% and 6.4%, fasting plasma glucose [FPG] of 100–125 mg/dL, or a 2-hour plasma glucose of 140–199 mg/dL during an oral glucose tolerance test [OGTT]), and more than 80% are unaware of their increased risk of progressing to diabetes.2 In 2019, an estimated 11% of the total U.S. population (more than 37 million people) was living with diabetes, while an additional 8.5 million were estimated to have undiagnosed diabetes.3 On a global scale, these numbers are even more concerning, with 50% of the 500 million people living with diabetes unaware they have the disease.Diabetes is classified as either diabetes mellitus type 1 (DMT1) or diabetes mellitus type 2 (DMT2). DMT1 accounts for approximately 10% of those who have been diagnosed with diabetes and occurs when autoimmune reactions destroy the insulin-producing beta cells and impair the body’s ability to make insulin. In DMT2, formerly known as adult-onset diabetes, the body is unable to use insulin efficiently. Of those diagnosed with diabetes, 90% are classified as having DMT2. Regardless of whether a person has DMT1 or DMT2, glycemic control is critical to avoiding complications of the disease; an estimated 74% of total diabetes expenditures are due to complications such as nephropathy, retinopathy, cardiovascular disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease, etc. Thus, early identification and treatment of the disease can improve health outcomes by avoiding or delaying long-term diabetic complications (Figure 1).4

Earlier screening for diabetes and prediabetes now recommended for all adults

In 2022, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) lowered the recommended screening age for prediabetes and diabetes for all people from 45 years to 35 years.5 Screening using HbA1c has several advantages over FPG and OGTT, including no requirement to fast, increased analyte stability compared to glucose, and fewer variations due to stress, diet, or illness.5 While both laboratory and point-of-care–based HbA1c assays can be used in monitoring glycemic control, the ADA recommends that testing for HbA1c should be performed using a method certified by the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) and standardized or traceable to the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) reference assay.5

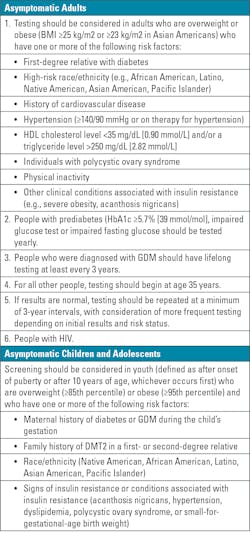

The ADA has defined risk-based screening recommendations for DMT2 and prediabetes in both asymptomatic adults and children. In overweight or obese adults (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) who have one or more additional risk factors as defined in Table 1, the ADA recommends testing for prediabetes and/or DMT2 regardless of age. The ADA recommends screening for prediabetes and/or type 2 diabetes in all adults beginning at 35 years of age and continuing at 3-year intervals as long as the test results are normal.5 The importance of screening and potential downstream benefits of improved clinical and other health outcomes have also been recognized in studies where workplace screening programs that include HbA1c have been implemented.6-8

Screening should also be considered in children who are overweight (≥85th percentile) and who have one or more additional risk factors as defined in Table 1. Children with additional risk factors should be screened and testing repeated at a minimum of 3-year intervals when results are normal. Depending on the initial screening results and risk status of the patient, more frequent testing should be considered.5

Why is the COVID-19 pandemic also a risk factor for diabetes?

Diabetes is now known to be one of the major risk factors for the development of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).9 Not only did the COVID-19 pandemic create challenges for the routine management of diabetic patients, it also made many populations more susceptible to developing diabetes, likely due to a variety of behavioral and lifestyle changes that affected dietary habits and exercise regimens. These include increased consumption of alcohol and sugary foods and decreased access to fresh food. Additionally, many studies have shown that the number of meals, snacking, and unhealthy dietary habits also increased during the pandemic. Furthermore, the closure of gyms and sporting clubs coupled with increased opportunities to work from home led to an overall more sedentary lifestyle due to reduced physical activity.10

Beyond lifestyle changes, the effects of the pandemic on diabetes care and management are well-documented, though the full extent of their impact is currently unknown. Lockdowns, social distancing, and quarantines led to a change in healthcare and a dramatic reduction in outpatient visits and laboratory testing. These factors contributed to gaps in diabetes management, such as significant reductions in testing for HbA1c, ultimately leading to missed or delayed diagnosis of diabetes and poor glucose control.9

Clinical studies suggest that COVID-19 is not only a lung disease, but also affects other organs such as the brain, heart, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, and endocrine organs.11 Another link between severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and diabetes is suggested by the ability of the virus to infect cells of the human exocrine and endocrine pancreas.11 The pancreatic localization of SARS-CoV-2 may lead to a dysregulation of cytokines and a proinflammatory environment that promotes an abnormal glucose metabolism.12

In summary, individual behavioral changes during the pandemic coupled with prior COVID-19 infections may have made many in the general population more prone to developing prediabetes and diabetes; many in this scenario likely remained undiagnosed. Therefore, it is critical to enhance access to diabetes screening and care by delivering a public health message that emphasizes the importance of diabetes diagnosis and management, with a focus on the younger adult population.9

Strengthening HbA1c surveillance programs increases population health

Diabetes is an important public health threat and one of the most common illnesses worldwide, with more than 500 million people affected, and its prevalence continues to rise. Use of available screening tests that detect the disorder in early asymptomatic stages enables the initiation of treatment and prevention efforts to improve long-term outcomes. HbA1c testing is an effective approach to identify asymptomatic patients with ongoing hyperglycemia. Patients often perceive HbA1c testing as more convenient than fasting blood glucose analysis, with no timing or dietary restrictions to be considered. A variety of automated laboratory-based methods are available for the large-scale analysis of HbA1c in patient samples using different analytical methodologies. Point-of-care HbA1c assays have also been shown to increase patient compliance for monitoring glycemic control, as they provide timely results and can be conveniently performed during a doctor visit.13 In addition, point-of-care HbA1c testing provides the opportunity for informed decision making regarding treatment plans and/or changes while the patient is still in the physician’s office.14 Together, both traditional and point-of-care HbA1c testing are important tools for effective and reliable diagnosis, monitoring, and management of diabetes, with the long-term goal of preventing serious and costly diabetes-related complications.

References

Barrett CE, Koyama AK, Alvarez P, et al. Risk for Newly Diagnosed Diabetes >30 Days After SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Persons Aged <18 Years - United States, March 1, 2020-June 28, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jan 14 2022;71(2):59-65. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7102e2.About the Author

Dr. Thomas Kampfrath, PhD, DABCC, NRCC

PhD, DABCC, NRCC

is a board-certified clinical chemist and medical officer for Siemens Healthineers.

Jeanne Rhea-McManus, PhD, MBA, DABCC, NRCC

Jeanne Rhea-McManus, PhD, MBA, DABCC, NRCC has been with Siemens Healthineers for 7 years, previously as a Medical Officer and currently as the Senior Director of Medical Science Information and Communication.