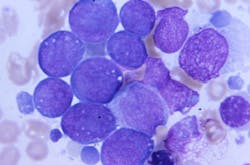

Researchers at the National Institutes of Health show the benefits of screening adult patients in remission from acute myeloid leukemia (AML) for residual disease before receiving a bone marrow transplant. The findings, published in JAMA, support ongoing research aimed at developing precision medicine and personalized post-transplant care for these patients.

Researchers in the current study wanted to show that screening patients in remission for evidence of low levels of leukemia using standardized genetic testing could better predict their three-year risks for relapse and survival. To do that, they used ultra-deep DNA sequencing technology to screen blood samples from 1,075 adults in remission from AML. All were preparing to have a bone marrow transplant. The study samples were provided through donations to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

After screening adults with variants commonly associated with AML, researchers showed that the two most common mutations in AML – NPM1 and FLT3-ITD – could be used to track residual leukemia. Among 822 adults with these variants detectable at initial diagnosis, 142 adults – about 1 in 6 – were found to still have residual traces of these mutations after therapy despite being classified as in remission.

The researchers found the outcomes for these patients striking. Nearly 70% of patients with the lingering NPM1 and FLT3-ITD mutations relapsed and just 39% survived after three years. In comparison only 21% of adults without this evidence of trace leukemia relapsed after three years and 63% survived.

In their analysis, the researchers also observed that adults with persistent mutations, but who were younger than age 60 and received higher doses of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy as part of their transplant preparation, were more likely to remain cancer free after three years than those receiving lower doses.

They also found that adults who didn’t receive stronger treatment before the transplant, which is now recommended as part of clinical guidelines, did better when this lower-dose therapy included a chemotherapy drug melphalan. However, more research is needed to evaluate these potential benefits and of other treatments, including targeted therapy for the FLT3-ITD mutation.