A sensor created by Johns Hopkins University graduate students to detect very early-stage lymphedema could spare thousands of patients a year, including many women with breast cancer, from the painful, debilitating condition, according to a news release.

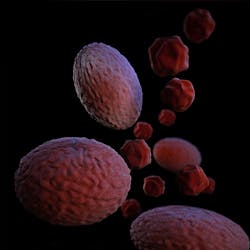

Lymphedema is a gradual buildup of lymphatic fluid in the extremities, often following cancer treatment, that causes swelling and pain. It's treatable if caught early, but once a patient feels something wrong, it's typically too late for low-impact treatment.

The inexpensive, non-invasive patch-like sensor would be the first tool available to allow patients to test their fluid levels at home, in about as much time as it takes to brush their teeth.

"Early detection is the key," said the creative team's co-leader Hunter Hutchinson. "We want to prevent the disease from getting to the point where a patient needs a long, complicated surgery."

The group of six students from the university's Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design (CBID) program started developing the sensor they call LymphaSense last year, adapting technology currently used to detect IV infiltration.

"The students on this team spent hundreds of hours in clinical rotations and discussions with doctors, nurses, and patient advocates, which helped them develop a deep understanding of the clinical need and the constraints within which a solution like the sensor must operate," said Youseph Yazdi, an Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering, faculty mentor for the team, and CBID's Executive Director. "The students also learned what it takes to develop a solution that's successful commercially, so that, most importantly, it has a chance to get developed and actually help patients."

Currently people at risk for lymphedema can only be tested at clinics or hospitals, although it's not uncommon for patients to be told to keep an eye on sensitive areas with a tape measure, which makes detecting the earliest signs of the disease inconvenient, if not impossible. But with the sensor, breast cancer patients and others at risk of lymphedema can apply the patch to their skin, and then a combination of biosensors will detect any trace of fluid buildup. Bluetooth technology sends the data to the patient's smart phone and doctors, who can then monitor the measurements.

"We considered a ring, a bracelet, and a cuff, but lymphedema can impact any part of the body, so a patch was the most feasible option," said co-lead Jennifer Schultz. "We created a solution that's effective, affordable, and could be used anywhere."

Interviews with more than 60 patients at Johns Hopkins Hospital provided the team invaluable insight into what patients need and want in a testing device. They further refined it with extensive tests on synthetic skin.

This summer the students will run a clinical study to test the device on patients. After that, they plan to submit a Food and Drug Administration application for the tool, aiming to have it available for medical use by 2025.

"The patients we've talked to have told us repeatedly the patch will empower them to have control over a condition they feel is often out of their control," Hutchinson said.