Why we should all care that “Everything is Tuberculosis,” and what we can do about it

To take the test online go HERE. For more information, visit the Continuing Education tab.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. List the epidemiological and healthcare statistics for TB infections worldwide and in the United States.

2. Discuss transmission mode and the current disease states of TB.

3. Discuss the various TB laboratory methodologies and their limitations.

4. List new innovations in the evolution of TB testing.

"Even though we’ve known the cause of tuberculosis for 140 years, there are still many mysteries about the disease,” states John Green in his 2025 book Everything is Tuberculosis: The History and Persistence of Our Deadliest Infection.1,2 The story unfolds through the eyes of Henry Reider, a 17-year-old from Sierra Leone who has suffered with tuberculosis (TB) for much of his young life. The author met Henry at a hospital in Lakka and Henry immediately took him to the hospital lab to see TB under a microscope. “He showed me the lab where a technician was looking through a microscope. Henry looked into the microscope, and then asked me to, as the lab tech explained that this sample contained tuberculosis even though the patient had been treated for several months with standard therapy.”

That’s where the hope for the elimination of TB lies — through laboratorians’ eyes. Henry’s – and so many others’ - stark reality underscores our critical role. In the same way that labs were indispensable during the COVID-19 pandemic by helping to diagnose, monitor and guide treatment, we are equally essential in the global effort to curb TB. Through precise, rapid diagnostics and strong infrastructure, laboratories can drive early detection, inform therapy and ultimately help stop transmission. Green’s book also contains broader information about TB diagnostics and argues for improving laboratory capacity in high-burden countries.

This brief article reviews tuberculosis demographics, transmission and available diagnostics, focusing on comparative considerations for laboratories performing IGRA testing, including collection requirements, preanalytical variables and technical pitfalls that may lead to invalid or indeterminate outcomes.

TB by the numbers: Then and now

TB is not a new disease. It can be traced back 9000 years, where it was found in the human remains of a mother and child buried together in a city now submerged beneath the Mediterranean Sea. The earliest written mentions of TB were in India 3300 years ago and in China 2300 years ago.3 Between the 1600s and 1800s in Europe, TB caused 25% of all deaths, with a similar impact in the United States.4 The New York City Department of Health and Hygiene published its first report on TB in the city in 1893. Dr. Robert Koch identified the bacterium on March 24, 1882, a date now commemorated each year as World TB Day to raise public awareness about the global TB epidemic.5

Fast forward to today, and despite over a century of progress and after decades of decline, tuberculosis has again become the world’s leading infectious disease killer. TB still devastates populations, especially where diagnostics, funding and care are limited. An estimated 25% of the world’s population has a latent TB infection (TBI). In 2024, approximately 1.2 million people died from tuberculosis and an estimated 10.7 million more people developed active TB disease (TBD), a population comprised of 54% men, 35% women and 11% children.6 Further, in the U.S., an active case of TB typically carries a mortality rate of about 7% within one year of diagnosis, with delayed mortality (beyond one year) of approximately 16%.7 Although U.S. mortality data for drug-resistant TB is unavailable, multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant TB fatality rates average 35% in studies in China and Peru.8,9

But there is some good news too. Globally, there was an overall drop in TB incidence in 2024 for the first time since 2020.

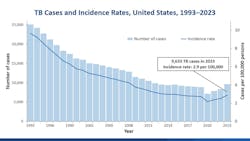

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) 2024 provisional data shows an estimated 13 million Americans have TBI and 10,347 TBD cases were provisionally reported.10 That’s a corresponding rate of 3 cases per 100,000 population, which is extremely low on the global scale of disease. The percentage increase in both TBD case counts (8%) and rates (6%) from 2023 to 2024 in the United States were less than the increases from 2022 to 2023 (15% in case count and rate) (See Figure 1). Thirty-four states and the District of Columbia reported increases in TBD case counts and rates from 2023 to 2024.

Consistent with previous years, in 2024 TB disease disproportionally affected non-US-born persons. Among US-born persons, there were 2356 (23%) provisionally reported TB disease cases with a corresponding rate of 0.8 per 100,000 persons. Among non-US-born persons, there were 7915 (76%) provisionally reported TB disease cases with a vastly higher corresponding incidence rate of 15.5 per 100,000 persons.

Tuberculosis: A spectrum of infection

Highly contagious, TB is an airborne infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), a member of the MTB Complex of pathogens. It usually affects the lungs but can also infect any part of the body, including all solid organs and even the eyes, ears, and brain.

For decades, TB infection has been dichotomized as either latent TB (TBI) or active TB disease (TBD). However, emerging research supports a more nuanced continuum that includes incipient and subclinical TB. Studies demonstrate that tuberculosis infection is actually a continuous spectrum of metabolic bacterial activity with antagonistic immunological responses. This paradigm shift in understanding has led to the proposal of two additional clinical states (incipient TB and subclinical TB), providing opportunities for early diagnostic and therapeutic interventions to prevent progression to TBD and transmission of TB bacilli.

Practically, this means that not everyone infected with TB mycobacteria will progress to TB disease, but they are in fact living with a fluctuating disease state — an epic battle between the immune system and the invading bacteria. That means infectivity is subtle, intermittent and very hard to detect.

Where do we come in as diagnosticians? We come in right here- at the beginning- with the careful and considered diagnosis of TB infection so that oral antibiotics can be initiated by the providers. Since TBI causes no symptoms or discomfort, most infected people are unaware of their condition. But without treatment, TBI can progress to TB disease and can also infect other people, repeating the relentless cycle of disease. This most often occurs when the previously healthy host’s immune system is challenged with a disease such as cancer or an autoimmune condition.

How does one prevent TBI from becoming TBD and how does TBD get treated? These options are worlds apart. Early TB infection, like that detected by interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs), is treated with short-course oral antibiotics and complete recovery is anticipated. TB disease regimens take many months to complete, require patient isolation and often cause permanent pulmonary dysfunction. Drug-resistant TB is very expensive to treat, often fatal and treatment regimens can last two years or more.

This is why screening, accurately diagnosing and treating TBI are focal points of global efforts to end TB, and how you play a crucial role in the global TB elimination effort. Due to diagnosis and treatment of both TBI and TB disease, the WHO estimates that more than 83 million lives were saved since the year 2000.6

Diagnostic options for TB infection

Without question, today’s laboratories have a growing role to play in support of newer, more specific, less subjective, and faster testing solutions and can spur use of new diagnostic tools over outdated skin testing techniques.

The tuberculin skin test

Tuberculin skin tests (TSTs) are over 100 years old. The tine test, a multipronged tuberculin skin test was used for about a century but was abandoned in about 2000 in favor of the Mantoux TST. Still in use today, the Mantoux TST is administered in a physician’s office, occupational health clinics, and even pharmacies. This test is not done in a laboratory setting.

The TST is a delayed-type hypersensitivity test requiring intradermal administration (usually in the forearm) of tuberculin units of purified protein derivative (PPD) solution. A follow-up visit is required within 48 to 72 hours so the results can be interpreted in the office by a licensed professional (registered nurse or higher). The reading of the test is a subjective, tape measure estimation of induration at the injection site. The reading should only be done by a registered nurse, since clinical correlation with the patient’s risk factors and medical history determine the result. For example, the induration size cutoff for a “positive” test result varies by risk category: >15mm for individuals without risk factors, >10mm for healthcare workers and >5mm for those with immune dysfunction, among many other variations. There is no straightforward “positive” or “negative” result, and a great deal of room exists for interpretation and error. A control is rarely, if ever, placed on the opposing arm, despite the CDC’s recommendation for their use.

Additionally, the TST can require up to four visits for the patient or job applicant, which creates a high non-compliance rate. In the case of a missed visit, the test must be redone with more follow-up visits. Moreover, the results of the TST test can be affected by the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination. TST can have a specificity as low as 59% in BCG-vaccinated patients, translating to an increase in false positive results from cross reaction with patients who have had the BCG vaccination.11 This is a critical point: Persons born in countries with medium and high endemicity for TB give BCG vaccination to prevent disease in children, but this results in unreliable TST results in the persons at highest risk for actually having TB infection.

The interferon gamma release assays

Interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) have become essential tools in the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, offering improved specificity over the tuberculin skin test and eliminating the need for return patient visits. As IGRA use expands globally and testing volumes rise, clinical laboratories continue to refine best practices to ensure accurate, reliable results.

Conducted from a single blood sample in the laboratory, IGRAs measure the immune response to TB-specific proteins, providing highly accurate, reproducible and objective results compared to TST. Three assays are currently approved in the United States: QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus (QFT-Plus), LIASON QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus and T-SPOT.TB. Both IGRAs measure secretion of cytokine interferon gamma (IFN-γ) as a marker of cell-mediated immune response to TB-specific peptides. The IFN-γ response provides an indirect indicator of infection. This interferon gamma is measurable, stable and typically absent from normal circulation. The degree of IFN-γ response does not differentiate between TB infection and TB disease presence.

The presence of both a negative and a positive control are two critical improvements over the TST that is shared by both the FDA-approved IGRAs. The negative control is the “nil” value reported on both tests. This is the quantity of IFN-γ (IU/ml for QFT-Plus; spots for T-SPOT.TB) that is measured in the negative control tube and is circulating in the patient’s blood as background immunologic function. The nil/background is later subtracted from the IFN-γ quantified in the antigen and mitogen components. The “mitogen” is the positive control, functioning primarily as an assurance that the patient has an intact immune system that is able to respond to a highly immunogenic stimulus, such as phytohemagglutinin.

The QFT-Plus test employs tube-specific technology that adheres heparin (all tubes), TB-specific antibodies (TB1 and TB2 tubes) and phytohemagglutinin (mitogen) to the assay tube walls. Whole blood drawn into the tubes must be immediately exposed to the walls of the tubes to initiate the cellular-level responses that release IFN-γ. After incubation and centrifugation, plasma IFN-γ is measured via ELISA or CLIA technology. For T-SPOT.TB, PBMCs are separated from whole blood and exposed to TB-specific antigens. A reagent is added to detect the IFN-γ and visually "capture" the spots where it is secreted. The number of spots in each well is counted.

To deliver these diagnostics effectively, laboratories must emphasize pre-analytical rigor, robust quality assurance and collaboration with clinical and public health partners. Blood collection for IGRA, for instance, demands careful handling to maintain viable lymphocytes, appropriate incubation times and timely processing.

2) QFT-Plus uses whole blood stimulation followed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or chemiluminescent detection of interferon-gamma. The assay evaluates both CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses, allowing a nuanced assessment of immune activity, particularly among those with recent or high-risk exposures.

a. In the registration trials and publications on QFT-Plus by Barcellini et al.,12-14 the isolated CD8 response was calculated by subtracting the quantitative values of TB1 from TB2 and was found to be potentially enhanced in the following conditions:

-

-

- Frequently in active, untreated pulmonary tuberculosis

- Among some persons with a higher risk for TB exposure

- Among some persons recently exposed to active TB

- Among some contacts who had a higher association to cumulative exposure and who were European-born (as opposed to being born in higher burden settings)

-

2) T-SPOT.TB isolates peripheral blood mononuclear cells from whole blood and uses ELISPOT methodology to count M. tuberculosis-sensitized T cells and capture interferon gamma in the vicinity of the T-cells from which it was secreted. The procedure involves isolating peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), typically using a density gradient method such as Ficoll to visualize the secreted proteins as spots on a plate.

In summary, IGRAs offer numerous benefits for both clinicians and patients. IGRAs are a single-visit screening test, they are highly accurate and they produce reproducible results. They are objective lab-based tests in comparison to the TST, which is subjective. For almost every patient population, these laboratory-based assays are favored for adults and children, especially in individuals who have received BCG vaccination or are unlikely to return for TST readings. In almost all settings, the CDC encourages their use over TSTs.15,16

A brief look at diagnostic options for TB disease

Beyond immunologic assays, molecular diagnostics have revolutionized active TB detection and treatment resistance profiling. Cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), such as Xpert MTB/RIF, provide rapid detection of M. tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance, often within hours. These molecular tools allow laboratories to identify both active disease and drug resistance, facilitating release from hospital isolation or timely initiation of appropriate therapy.

TB tests in the pipeline

Emerging high-throughput molecular platforms, point-of-care PCR assays, cfDNA, CRISPR and innovative phenotypic resistance testing are in varying stages of study and FDA application to expand laboratory capabilities. For example, biosensor-based detection of lipoarabinomannan (LAM) in urine and machine-learning-based screening approaches, such as audio-based cough analysis, show promise as rapid, low-cost diagnostic adjuncts for TB disease detection, particularly in resource-limited countries.

Shared responsibility

Healthcare systems must integrate these diagnostic tools with evidence-based testing protocols to maximize clinical impact. For laboratories, implementation requires careful attention to specimen collection, workflow optimization and quality assurance. Staff training, calibration and periodic competency assessments ensure accurate, reliable results. Laboratory teams should work closely with their clinicians and public health partners, facilitating confirmatory testing, sharing resistance profiles and contributing to TB surveillance databases.

Today’s guidelines and recommendations for TB testing

Both TST and IGRA tests are approved for use in the United States, and both are generally covered by Medicare, Medicaid and private insurance plans.

- In 2016 and again in 2023, the CDC and the US Preventive Services Task Force have recommended testing people who are at increased risk for TB infection.17

- In 2017, the American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America (ATS/IDSA) guidelines recommended IGRAs over TST in individuals aged five and older who meet any of the following criteria:16

- Likely to be infected with MTB

- Have a low or intermediate risk of disease progression

- Have had a BCG vaccination, or

- Are unlikely to return to have a TST read18

- In 2019, the CDC and the National TB Controllers Association recommended healthcare worker testing be conducted on hire and after exposure, with a greater emphasis on encouraging treatment of early infection in lieu of annual testing.18,19

- In 2024, the American Academy of Pediatrics lowered the recommended age for IGRA use to include all ages.20

The path forward

Effective TB elimination requires thoughtful testing strategies. High-priority populations include close contacts of TB disease cases, individuals from high-burden regions, people living with HIV, young children and immunocompromised individuals. These groups benefit most from the sensitivity and specificity of IGRAs, and benefit from early TB preventive therapy treatment to prevent progression to active disease, which is more likely in these immune-compromised patients.

Our laboratories are not observers in the TB ecosystem. We are active, strategic partners in global elimination efforts. By scaling up IGRAs, harnessing rapid molecular diagnostics and supporting resistance testing, laboratories deliver the precision and speed that TB control demands. As we expand capacity, refine and automate workflows and strengthen collaborations, laboratories will continue to drive progress in tuberculosis control. This work brings us closer to a future where TB is rapidly and accurately diagnosed, treated before it can reactivate and become infectious and ultimately eliminated.

REFERENCES

- Green J. Everything Is Tuberculosis: The History and Persistence of Our Deadliest Infection. Random House; 2025.

- Thanassi SJ, Thanassi WT. Why we should all care that everything is tuberculosis. J Occup Environ Med. 2025;67(10):e766-e767. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000003483.

- Global Tuberculosis Report 2024 Factsheet. World Health Organization. Published 2024. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/global-tuberculosis-report-2024-factsheet.

- TB 101: TB history (1/2). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/webcourses/tb101/page2621.html.

- History of World TB Day. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/world-tb-day/history/index.html.

- Global Tuberculosis Report 2025. World Health Organization. Published 2025. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-tuberculosis-report-2025.

- Lee-Rodriguez C, Wada PY, Hung YY, Skarbinski J. Association of mortality and years of potential life lost with active tuberculosis in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2014481. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14481.

- Chung-Delgado K, Guillen-Bravo S, Revilla-Montag A, Bernabe-Ortiz A. Mortality among MDR-TB cases: comparison with drug-susceptible tuberculosis and associated factors. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119332. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119332.

- Frank M, Adamashvili N, Lomtadze N, et al. Long-term follow-up reveals high posttreatment mortality rate among patients with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in the country of Georgia. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(4):ofz152. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz152.

- Tuberculosis provisional data for 2024. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/tb-data/2024-provisional/index.html.

- Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D. T-cell-based assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(3):177-184.

- Barcellini L, Borroni E, Brown J, et al. First independent evaluation of QuantiFERON-TB Plus performance. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(5):1587- 90. doi:10.1183/13993003.02033-2015.

- Barcellini L, Borroni E, Brown J, et al. First evaluation of QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus performance in contact screening. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(5):1411-1419. doi:10.1183/13993003.00510-2016.

- Viana Machado F, Morais C, Santos S, Reis R. Evaluation of CD8+ response in QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus as a marker of recent infection. Respir Med. 2021;185:106508. doi:10.1016/j. rmed.2021.106508.

- Latent Tuberculosis Infection Testing and Treatment: Summary of U.S. Recommendations [PDF]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Tuberculosis Controllers Association. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/104205/cdc_104205_DS1.pdf.

- Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention clinical practice guidelines: diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(2):111-115. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw778.

- Latent tuberculosis infection in adults: screening. US Preventive Services Task Force. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/latent-tuberculosis-infection-screening.

- Sosa LE, Njie GJ, Lobato MN, et al. Tuberculosis screening, testing, and treatment of U.S. health care personnel: recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(19):439-443. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6819a3.

- Thanassi W, Behrman AJ, Reves R, et al. Tuberculosis screening, testing, and treatment of US health care personnel: ACOEM and NTCA joint task force on implementation of the 2019 MMWR recommendations. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62(7):e355-e369. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001904.

- Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://publications.aap.org/redbook/book/755/red-book-2024-2027-report-of-the-committee-on-infectious-diseases.

To take the test online go HERE. For more information, visit the Continuing Education tab.

About the Author

Wendy Thanassi MD, MA, MRO

completed her B.A. at Yale as a double major, summa cum laude, in Biology and African Studies, followed by medical school at Stanford University with an M.D. and a concurrent Master’s degree in International Economics. She then returned to Yale New Haven Hospital for Emergency Medicine residency. Dr. Thanassi has worked on multiple volunteer and research projects in Thailand, Papua New Guinea, Australia, South Africa and Namibia. Professionally, she worked for the US. Department of Veterans Affairs as a Chief of Occupational Health for 16 years leading the national TB testing programs for their 300,000 healthcare workers, and was a Professor at Stanford Medicine. She sits on the CDC’s Advisory Council for Elimination of TB; and is the US Representative to the International Congress on Occupational health representing all employed Americans. In January 2024, Dr. Thanassi joined QIAGEN as the Senior Medical Director for TB & Infectious Diseases in North America.