As the pandemic meets flu season, labs turn to rapid molecular testing

Earning CEUs

For a printable version of the September CE test go HERE or to take test online go HERE. For more information, visit the Continuing Education tab.

Passing scores of 70 percent or higher are eligible for 1 contact hour of P.A.C.E. credit.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Upon completion of this article, the reader will be able to:

1. Describe technical and-non-technical challenges labs face in diagnosing patients during a season marked by both flu and COVID-19.

2. Describe the advantages and disadvantages of different types of assays for diagnosing respiratory diseases such as flu and COVID-19.

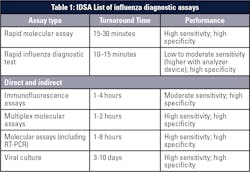

3. Recall the Infectious Disease Society of America’s (IDSA) recommendations on the preferred assays for diagnosing flu.

4. Describe how combination molecular assays can be used to detect the presence of multiple respiratory diseases from a single specimen.

The upcoming 2020-2021 flu season promises to bring new challenges for diagnosing and treating patients. While flu season is predictably unpredictable, never before have we faced its onset while simultaneously fighting a non-flu respiratory pandemic. Problems typically encountered during flu season are likely to be compounded by the COVID-19 landscape.

The challenges of respiratory testing during flu season are well known. Influenza causes many symptoms shared with other respiratory infections – and indeed even with some other respiratory conditions not associated with pathogens – making it difficult to diagnose. Answers are needed quickly, but historically, rapid tests, such as immunoassays for viral antigens, were far less accurate than conventional laboratory tests. A broad range of molecular test options, from flu-only tests to broad panels of respiratory pathogens, has been helpful for the laboratory but can be confusing for physicians to navigate. The right test for one patient can be entirely wrong for the next patient. For lab managers, knowing how many tests, reagents, and other supplies to stock in preparation for getting through flu season can be difficult as well.

And those are just the expected hurdles in a regular flu season. This fall and winter, physicians and clinical lab professionals will have to add the new variable of COVID-19. At a minimum, the pandemic means that clinical labs will not be able to rely solely on tried-and-true flu tests. Depending on local prevalence of COVID-19 infections, each lab will have to determine whether to add SARS-CoV-2 testing for all patients with respiratory symptoms, or whether they will need an algorithm to select which patients get tested for both flu and COVID-19.

As of July, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had already granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for three combination tests for flu and SARS-CoV-2, including one developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).1 Other diagnostic manufacturers will likely make similar tests available. While this will be good for patients and healthcare providers, it places the burden of validating new assays on clinical lab teams already stretched thin by the pandemic.

Respiratory testing challenges

However, the choice of test has changed. With the major push to slow the spread of antimicrobial resistance by reducing the unnecessary use of antibiotics, physicians can no longer wait a few days to get test results for possible flu cases. There is now significant pressure to deploy assays that generate rapid results.

Unfortunately, some tests have enabled fast results at the cost of accuracy. Rapid antigen flu tests have been widely adopted in recent years, particularly in doctors’ offices and other outpatient environments where getting results in 15 minutes represented a huge advance for patient care. But numerous studies have shown that rapid antigen tests tend to have low sensitivity, leading to a high number of false negative results.

New guidelines for influenza testing issued by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) last year recommend against the use of rapid antigen tests. A broad survey of many studies found “pooled sensitivities of 54 percent and 53 percent to detect influenza A and influenza B virus antigens, respectively,” according to the new guidelines.2

Confounded by COVID-19

Clinical lab professionals have never experienced the vagaries of flu season while also battling a worldwide, non-flu respiratory pandemic. It remains to be seen exactly how the COVID-19 situation will compound the challenges of respiratory testing, but we can make some educated guesses.

It is possible that the 2020-2021 flu season could be significantly alleviated by measures many people are already taking to avoid being infected by SARS-CoV-2, such as mask wearing and social distancing. These are the same measures recommended for reducing the spread of influenza, though in the United States most people do not dramatically alter their behavior to avoid the flu.

Similarly, if the substantial reduction in domestic and international travel seen so far in 2020 continues into flu season, this could also limit the spread of influenza. Even if some travel resumes, restrictions that prevent people from certain countries from entering other countries or regions could have the secondary benefit of leading to a milder flu season.

Those are the potential upsides of COVID-19 on the flu landscape. Among clinical laboratories, there is far more focus on the possible downsides.

The SARS-CoV-2 testing fiasco that played out in the United States, as the pandemic reached this country, has not yet been overcome. Capacity limits have in many cases prevented labs from reporting results in a timely manner, even when the tests they use take just hours to generate data.3 Supply chain problems have made some test reagents and equipment difficult to stock.4 These challenges may well follow us into flu season and could make it harder for labs to manage even low levels of influenza testing.

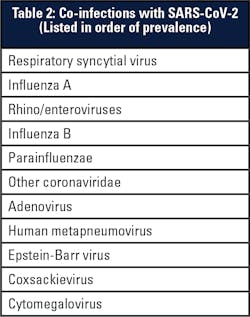

Because the symptoms of COVID-19 are maddeningly non-specific, labs will likely have to run flu and SARS-CoV-2 tests for each patient suspected of having a respiratory infection, or they will have to validate and implement new tests that encompass those viruses, as well as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), another common culprit in respiratory infections.

Finally, we must anticipate the confounding variable of co-infections. Studies published from earlier in the pandemic, which reviewed data from the tail end of the previous flu season, found that influenza A and RSV were the most common viruses seen in COVID-19 patients with co-infections.5,6 Currently there is insufficient data to determine the effect of such co-infections on clinical outcomes, but it is possible that the severity of a SARS-CoV-2 infection is altered by the presence of other pathogens. Therefore, it will be important for clinical laboratories to have the necessary tools to detect cases of co-infection as flu season ramps up.

Using molecular diagnostics

With many options to choose from, molecular assays also tend to be amenable to tailoring for specific needs of various patient demographics. Molecular tests can be used to detect a single pathogen (e.g., SARS-CoV-2), a few related pathogens (e.g., influenza A and B), a handful of common pathogens that cause similar symptoms (e.g., influenza A/B and RSV), or the majority of organisms commonly associated with respiratory symptoms (including viral and bacterial pathogens). During a typical flu season, an otherwise healthy patient would likely need to just test for flu A/B and RSV. Meanwhile, an immunocompromised patient admitted to the hospital could be tested with a broad panel of respiratory pathogens, as the IDSA flu guidelines recommend.

In the COVID-19 era, this flexibility will also be important, but this time the SARS-CoV-2 virus must be factored in. A mini panel test including flu A/B, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2 will be an important tool to help lab staff quickly test for the most common respiratory pathogens without over-testing, giving them the ability to detect common viral co-infections from a single assay. The recently released CDC test, covering SARS-CoV-2 and flu A/B, could be an important tool for clinical labs this fall and winter.9 Numerous other respiratory assays incorporating COVID-19 are likely to be available as well.

Another key feature of molecular diagnostics is their ease of use. While the first wave of molecular tests was reserved for use in high-complexity laboratories, more recent molecular platforms have been streamlined to allow their use in labs of moderate complexity or the CLIA-waived setting. Today, there are a number of sample-to-answer platforms that rely on automation to limit the hands-on time needed from lab technicians. Some tests are as straightforward as loading samples into a cartridge or cassette, insertion into an automated instrument, and pressing the “start” button. In addition to easing the burden on medical technologists, these kinds of platforms also make it easier for labs to scale capacity to meet surges in demand, without requiring extra staffing resources.

These automated platforms can also provide rapid turnaround times. Some instruments require as little as 20 minutes to report results, and many others take just a few hours. This gives clinical labs many options for respiratory testing, while facilitating same-day reporting of results back to physicians and patients for optimal treatment or isolation protocols.

Last but not least, the multiplexing capability of molecular tests – that is, the ability to detect more than one pathogen from a single assay – should ease the pressure on the supply chain. Having to test for COVID-19 and flu separately requires two nasal swabs, two test kits, and twice as many reagents. By multiplexing these in a single test, lab staff will be able to conserve precious resources and samples and test more patients without running out of supplies.

Other factors

Reimbursement is always a testing concern, and the addition of COVID-19 in flu season could increase the complexity of managing costs for labs and patients. Both public and private payers have strongly preferred targeted testing to broad panel testing in many situations.10 With the urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is reasonable to hope that insurers will consider a panel covering at least flu and SARS-CoV-2 as the most responsible approach and reimburse accordingly. But as of this summer, these important determinations had not been made. Lab managers may have to plan for a targeted panel test but have a backup plan available for reimbursable single-pathogen tests for certain groups of patients if needed.

Predicting flu testing volume may also be more difficult than usual this year. In addition to the usual unknowns related to how effective the new flu vaccine will be (it typically falls between 20 percent and 60 percent), there is the additional complexity of estimating how many people will get the vaccine.11 While the ongoing pandemic may motivate more people to get vaccinated due to their increased fears of getting sick, it may also depress vaccination rates if people are too afraid of getting COVID-19 to go to the doctor’s office or the pharmacy for a flu shot. This will put extra pressure on clinical labs to plan for testing capacity, which may be much lower than usual, much higher than usual, or anywhere in between. Having automated molecular diagnostic platforms that can handle stat or batch testing with minimal hands-on time will help laboratory teams deal with unexpected peaks in demand.

Another factor with unknown consequences is the adoption of pooled testing as a strategy to increase capacity for detecting SARS-CoV-2. The purpose of pooled testing is to alleviate the strain on testing resources and reduce the number of tests required by combining samples in a single diagnostic run. The strategy only works, though, if COVID-19 prevalence in a community remains low. In that case, the majority of tests will come back negative and no further testing needs to be done. But if the positivity rate rises, more pooled samples will test positive, which will require further testing of each individual sample and not lead to a net decrease in the total tests required. The test used would also have to be exquisitely sensitive to be able to detect a positive that has been diluted by other samples, or there would have to be a concentration step prior to processing. If sample pooling becomes widely used, it could reduce demand for combined SARS-CoV-2/flu tests during flu season, at least in regions where the prevalence of COVID-19 infections remains low.

In Review

Bracing for flu season is challenging for most clinical labs even in the best of times. With the COVID-19 pandemic, though, laboratories will face an unprecedented respiratory testing situation this fall and winter. Rapid molecular tests and flexible platforms that allow for multiplexing several pathogens in a single assay will be an essential tool for dealing with the potential crisis that lies ahead of us and should help to ease the supply chain stress associated with dramatically higher testing rates.

References

1.Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA authorizes additional COVID-19 combination diagnostic test ahead of flu season. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. July 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-additional-covid-19-combination-diagnostic-test-ahead-flu. Accessed July 20, 2020.

2. Uyeki, T.M., Bernstein, H.H., Bradley, J.S., Englund, J.A., et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2018 update on diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis, and institutional outbreak management of seasonal influenza, Clin Infect Dis, Volume 68, Issue 6, 15 March 2019, Pages e1–e47, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy866.

3. Mervosh, S., & Fernandez, M. (2020, July 07). Months into virus crisis, U.S. cities still lack testing capacity. NYT https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/06/us/coronavirus-test-shortage.html. Accessed July 6, 2020.

4. Moses, J. (n.d.). Supply chain analysis of COVID-19 testing: IBISWorld Industry Insider. https://www.ibisworld.com/industry-insider/coronavirus-insights/supply-chain-analysis-of-covid-19-testing/. Accessed July 9, 2020.

5. Lai, C., Wang, C., & Hsueh, P. (2020). Co-infections among patients with COVID-19: The need for combination therapy with non-anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents? Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2020.05.013.

6. Lansbury, L., Lim, B., Baskaran, V., & Lim, W. S. (2020). Co-infections in people with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Infection. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.046.

7. Miller, Shelley A., et al. “Comparison of the AmpliVue, BD Max System, and Illumigene molecular assays for detection of Group B Streptococcus in antenatal screening specimens. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, vol. 53, no. 6, 2015, pp. 1938–1941., doi:10.1128/jcm.00261-15.

8. Couturier, B. A., Weight, T., Elmer, H., & Schlaberg, R. (2014). Antepartum screening for Group B Streptococcus by three FDA-cleared molecular tests and effect of shortened enrichment culture on molecular detection rates. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 52(9), 3429-3432. doi:10.1128/jcm.01081-14.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnostic multiplex assay for flu and COVID-19 and supplies. July 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/multiplex.html. Accessed July 9, 2020.

10. Ibbotson, S. (2019, May 14). Paying for molecular diagnostics. CLPMAG http://www.clpmag.com/2019/05/paying-molecular-diagnostics/. Accessed July 9, 2020.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Past seasons vaccine effectiveness estimates. January 29, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/past-seasons-estimates.html. Accessed July 9, 2020.

About the Author

Sherry A. Dunbar MBA, PhD

serves as Senior Director of Global Scientific Affairs for Luminex.