According to the results of Medical Laboratory Observer’s 2021 annual salary survey of laboratory professionals, average salary has increased and job security remains high, but the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the profession’s staff shortages, with 80 percent of respondents noting shortages having a “moderate to large impact” on operational efficiency.

We present key findings from the annual survey, as well as insights from U.S. lab professionals on compensation, job security and satisfaction, education and training, changing roles and responsibilities, technology adoption, and how COVID-19 has impacted their teams and operations over the past year.

Average salary on the rise

Average compensation of laboratory professionals across the board rose $4,044, from $93,844 in 2020 to $97,888 in 2021. While men still report the highest average salary (at $103,233), the average salary for female lab professionals grew slightly more than that of their male colleagues from 2020 to 2021, with females earning $4,509 more on average, and males earning $3,454 more. The average expected base salary for all lab professionals in 2021 was far higher than last year, at $92,500 compared with $72,500.

When asked if they received a pay increase in 2020, 63 percent of respondents said “yes,” which was down from 2019 (at 71 percent). Although 10 percent more lab professionals reported bonuses in 2020 compared with 2019, or 38 percent versus 28 percent, with regards to raises, about half (48 percent) said they anticipate a 2-4 percent pay increase, and 21 percent expect their raise to be less than 2 percent.

2021’s snapshot

The information gathered from the survey is based on 312 respondents. This year’s composite clinical lab professional is female, between 56-65 years old and holds a salaried, management position in a hospital lab. She has been in the lab profession an average of 26 years and has worked for her current employer for 17 years.

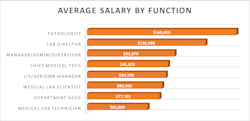

Some positions see large pay leaps, others drop since last year

Salaries increased in 2021, compared with 2020, for most lab positions, with pay for both medical lab scientists and medical lab technicians up 24 percent ($80,500 and $65,000 respectively), lab directors up 10 percent ($126,938) and pathologists up 7 percent ($160,000).

Other positions reported more moderate average salary gains. For example, salaries for lab managers, administrators, and supervisors were up 4 percent ($93,879), while chief and assistant chief medical technologists saw salaries increase 4 percent ($86,833).

The average pay for section managers and department heads was down 6 percent compared with last year ($77,703), while the salary for LIS/EHR/EMR managers was down only slightly, by less than 1 percent ($84,500).

“While salaries have improved for medical laboratory scientists, the salaries of other professions have as well – and some have improved at a faster pace. This makes it difficult to entice college students to choose this profession. In fact, my own daughter has told me that she can get just as much education and make much more money as a nurse,” Radford said.

Lab size and location make a difference

Professionals working in larger labs continue to earn higher salaries. Among the largest labs, those with more than 100 employees, the average salary was $115,873 in 2021. The average salary for those working in labs with 51-100 employees was $101,535, labs with 21-50 employees $91,336, 11-20 employees $86,560, and 1-10 employees $83,128.

As for testing volume, the highest average salaries were reported at either end of the spectrum, with those in labs running more than 2 million tests earning $115,516 on average in 2021, and those in labs running fewer than 25,000 tests earning an average annual salary of $107,900. In between this range, average salary increased by volume of tests performed:

- 25,001 to 50,000 tests: $81,917

- 50,001 to 100,000 tests: $87,891

- 100,101 to 500,000 tests: $91,053

- 500,001 to 1 million tests $93,596

- 1-2 million tests: $102,695

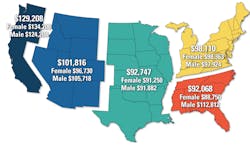

Lab professionals working in the Pacific region of the United States once again report the highest pay at $129,208 on average annually, up from $121,825 in 2020. Those working in the Mountain States reported the largest pay gains over last year, up 14 percent (from $89,625 to 101,816), followed by the Southeastern States, with a 10 percent increase in average annual salary (from $83,649 to $92,068), and the Central Region, with a 6 percent increase (from $87,365 to $92,747). Lab professionals in the Northeast saw only a slight increase (from $97,778 to $98,110).

Job security is high because staffing is low

Even though 32 percent of those surveyed said their labs furloughed employees during the pandemic, the vast majority of respondents reported their job security as “very secure” (54 percent) or “somewhat secure” (40 percent). Among those surveyed, 22 percent have been with their current employer for more than 30 years, with an additional 20 percent reporting a tenure of between 20 and 30 years with the same employer.

“Currently, jobs are very secure in the clinical laboratory world,” said Misha M. Tate, MBA, BS, MT (ASCP) SMCM, Director of Laboratory Services, Mon Health Medical Center, Morgantown, WV. “ Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a high demand for qualified personnel to perform point-of-care testing for COVID, as well as more complex molecular tests for COVID. Qualified lab personnel will always be needed to perform testing, interpret results and troubleshoot analyzers. Hopefully, the awareness of the need for lab personnel will catch the attention of the younger generation and encourage them to pursue a lab career.”

When asked what impact the current shortages of medical personnel have on their lab operational efficiency, 80 percent of those surveyed said it has a “moderate or large impact,” compared with 73 percent last year. Yet, only 23 percent said the shortage caused their lab to outsource more tests during 2020.

Competition from the nursing field, an aging population of individuals in the lab profession, and the changing nature of lab work are three major factors driving staff shortages, according to Marallo.

“The lack of new graduates sufficient to replace the aging body of med techs is a trend that has been developing for at least 10 years - maybe longer. Young students interested in a medical professional role are gravitating towards nursing as a career choice due to the better pay and less rigorous academic requirements. I have also spoken to some students interested in the lab as scientists, but they are turned off by the increases in automation that effectively ‘takes the science out of the job,’ to quote one student. I’m not sure if I agree with that perspective, but it is true for some labs that keeping an automated platform in operation is more of a biomedical/computer chore than it is a medical laboratory science function,” Marallo said.

Benefits remain stable across the board

With regards to benefits for lab professionals, the 2021 survey results were similar to past years. Nearly all respondents said their employers offer health insurance, dental insurance, vision insurance, and a 401(k) plan or pension. There were some slight increases and decreases in other benefits categories:

- Paid time off increased from 85 percent in 2020 to 87 percent in 2021

- Paid holidays increased from 58 percent in 2020 to 63 percent in 2021

- Childcare increased from 5 percent in 2020 to 6 percent in 2021

- Life insurance decreased from 88 percent in 2020 to 86 percent in 2021

- Disability insurance remained stable at 78 percent in 2020 and in 2021

- Flex time decreased from 13 percent in 2020 to 12 percent in 2021

- Overtime pay decreased from 33 percent in 2020 to 31 percent in 2021

- More than one-third of respondents (35 percent) say their employers provide paid COVID-19 specific leave.

Education remains a priority for lab professionals

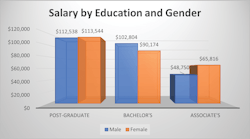

As in past years, the majority of those lab professionals surveyed hold bachelor’s or post-graduate degrees, at 61 percent and 30 percent respectively. An additional 7 percent hold associate degrees, and only 1 percent said their highest level of education attained is a high school diploma. Again, lab professionals with post-graduate degrees earned the most, with a reported $113,758 average annual salary in 2021.

As Brown explains, there is an urgent need to attract students into lab degree programs to sustain the future of the industry. “With so many preparing for retirement, we have to do everything we can to fill classes for both four-and two-year degrees,” said Brown. “Without staff, we will be forced to resource out valuable patient tests and exist with stat-labs that are limited in capacity and menu. Having the ability to perform most of the requested testing that comes through our hospital laboratory is vital to exceptional, safe, high-quality healthcare,” Brown said.

The majority of survey respondents (76 percent) hold certifications from the American Society for Clinical Pathology, 13 percent from state governments and 10 percent from the National Credentialing Agency for Laboratory Personnel (NCA).

As for continuing education, 25 percent of respondents say they earned between 11-20 hours of continuing education credits in 2020, and 18 percent earned more than 20 hours.

Greater recognition, collaboration and expanding roles

Those interviewed for this article agree that the pandemic has highlighted the importance of the lab profession, instilling pride in those individuals who are playing a critical role in the diagnosis of millions of patients who have contracted the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the U.S.

“I try to remind my staff regularly of the enormous impact that they’re making on the health and well-being of our community,” said Radford. “While this has always been the case, it has never been so ‘front and center’ as it has now during the COVID-19 pandemic. Not just from the perspective of testing, but also the care that we’re helping provide for the sickest of sick in our community. The expediency of our results has helped expedite the care to the patients when our hospital has been at heightened census – particularly ICU beds. I have seen such pride from my team, as well as the teams of other clinical laboratory leaders that I know.”

Brown describes how her team worked with the sterile processing department for their health system on a strategy to address supply shortages during the pandemic.

“When testing became widely available, we realized quickly that supplies for testing were strained. We were unable, like so many, to obtain viral media and nasopharyngeal swabs for testing. Our brilliant team of physicians, pathologists and technologists put their minds together and were able to produce our very own viral transport media and 3D print collection swabs. Our sterile processing department came up with a process for the safe sterilization and packaging of the swabs. This carried us through the peak of testing demands from late April through the summer months in Nebraska. We still have these supplies on hand, ready to use at any time when commercial materials again become strained,” Brown said.

Tate explains that some staff in the lab may have been reassigned to new tasks as testing needs changed. “During the height of the pandemic, many hospitals decreased or ceased performing elective operating room (OR) procedures,” said Tate. “This led to staff being re-assigned to perform tasks that they were not accustomed to, such as transporting supplies and samples back and forth to COVID testing stations.”

Brown and her team have also found themselves shifting staff resources to meet changing needs during the pandemic. Early on, before COVID-19 testing was available in their lab and normal volumes of cultures and other testing decreased dramatically, they redeployed several staff members in microbiology to the collection of samples. In the late spring 2020, when testing became available, they not only continued to use multiple staff members for collections, but also had one or two technologists dedicated to running tests during their entire shifts.

Brown is not alone. Among those surveyed, 33 percent said they have had to reassign lab employees to other areas to address COVID-19 testing demands. Brown describes how her team has addressed knowledge gaps among staff members assigned to new roles.

“Prior to the pandemic, there was always a focus on having enough generalist technologists on staff, so we could shuffle where we needed to when workflow changed,” said Brown. “Now, we realize more than ever that we need not only generalists, but the specialties, such as microbiologists, are just as in demand. We had to get creative and cross train support laboratory staff members to function in roles they never had been asked to serve before. Those staff rose to the challenge, and we are very proud of what we accomplished and continue to provide for our patients.”

There was a noticeable decrease in number of labs performing outreach to other organizations in an effort to build test volumes, compared with last year, as 39 percent said their labs have performed minimal or no outreach efforts at their organizations, compared with 29 percent in 2020. Those performing outreach varied by type of organization:

- Physician’s practices: 51 percent

- Nursing homes: 37 percent

- Community members: 32 percent

- Home care: 18 percent

- Other laboratories: 17 percent

A heightened focus on process efficiency drives adoption of new technologies

When asked how their lab department was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, more than one-third (33 percent) of survey respondents said they updated their processing policies, and 29 percent reviewed test and utilization costs, as well as reimbursement levels.

An increasing number of lab professionals report that their organizations have automated or further automated new procedures – 51 percent, up from 42 percent last year.

“The capabilities of the various lab information systems that exist today have come a long way in assisting clinical laboratory management in keeping a finger on the pulse of operations,” said Radford. “With the improvements that have been seen, we have more information that can help make better decisions; this information is at our fingertips.”

“However, this is not something that will just come because you have it,” she added. “It takes time and experience to comfortably utilize the myriad of data at our access and not be overwhelmed by ‘analysis paralysis.’ The details are what drives our day-to-day work in the clinical laboratory, so it’s easy to get lost in the minutia of the information. It is important to keep the overarching purpose of the data review top of mind to remain focused, and let the information work for your operation’s benefit.”

Tate sees clinical labs increasing their use of data analytics to improve upon operational and financial challenges, as well as using the information to support value-based care.

“This is especially evident in antibiotic stewardship,” said Tate. “Through electronic reporting and data sharing, labs are readily able to gather information about their own entity, or even other entities, throughout the nation. By collaborating with pharmacy, infectious disease physicians and other key stakeholders, they can help identify any trends that may cause an increase in the incidence of multi-drug resistant organisms. Keeping our patients safe is of the utmost importance. By decreasing the incidence of these multi-drug resistant organisms, we also decrease pharmacy costs and decrease patient length of stay.”

On the topic of molecular diagnostics adoption, more than 80 percent said they have embraced it in microbiology, up from 73 percent in 2020. Other top areas for molecular diagnostics include chemistry (14 percent), hematology (6 percent) and blood bank (3 percent).

“One major trend that is actually making our profession more ‘fun’ is the introduction of more molecular testing in a sample-to-answer format,” said Radford. “We’re seeing more and more small and mid-sized analyzers that give the capability to perform molecular testing without the need for extraction material, clean rooms, and all of the other aspects of a molecular lab. This has increased the ability for smaller clinical labs to provide the great technology to the patients of their community without necessarily increasing the cost – and, in some instances, decreasing the cost. One of the best ways to demonstrate the impact that this technology has had is the fact that many microbiology labs are more automated now than they ever were in the not-so-distant past.”

Looking toward the future

The lab professionals we interviewed for this article agree that there is a bright future for the clinical lab profession, with strong job security and an increased recognition for the role labs play in the supply chain of patient care.

“Since the average age of Med Tech is increasing, and many are retiring, there are jobs available, and I think a good tech in the right lab can count on a secure future,” said Marallo.

The COVID-19 pandemic, with its pressing need for rapid and accurate testing results, has shined a spotlight on the work of clinical lab professionals.

“There has been a drastic change in how clinical labs are portrayed,” said Tate. “Lab testing has historically been more of a behind-the-scenes role that is now being brought into the spotlight. People are more aware of some of the different types of testing that take place in a clinical lab. They have also become more aware of the constraints that cause delays in testing.”

“The pandemic has brought to light that there are more professionals in healthcare than doctors and nurses,” said Brown. “For the first time in my 18-year career, I feel the world actually knows that the medical laboratory science profession exists. We have always been here, behind the scenes, working to serve our patients. I am hopeful that this recognition of our work will increase the interest in our profession and help us for years to come as we face severe staffing shortages.”

But more work is needed to address industry challenges, including competition from other areas of healthcare, most notably nursing, that can divert young professionals away from lab careers with promises of greater compensation and growth opportunities.

One way for clinical lab to raise its profile in the healthcare field, better promote its contributions to patient care and advance both individual lab professionals and the profession as a whole is through greater collaboration throughout the care continuum.

As Radford explains, this requires lab leaders to be positive and proactive champions for their teams. “I know of many more laboratory professionals who are making a difference outside of the four walls of the lab,” said Radford. “However, in order for this to happen and for the value of the contributions from the lab to be realized, the department leader has a responsibility to ‘manage up’ what his/her team has to offer. Participation on multi-disciplinary committees is one key way for the lab to make a name for itself. Often, the department leader(s) represent the laboratory on these committees. A recommendation that I would have is for the leaders to tap into the resources within the ranks of the department, giving others an opportunity to participate as well. This is actually a win-win for everyone involved. The leader has an opportunity to decrease the many meetings on their schedule, and the staff members have an opportunity to grow.”