When expressing the breadth of the risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), a colleague of mine often shares the stark perspective, “If you’re having sex, you’re at risk.” And she’s right. While sex is rarely discussed in an open and candid fashion, it is important to remember that sexual health is health, and encompasses all aspects of human sexuality. Sexual health and satisfaction are key components of health and well-being.1

We are accustomed to thinking about sexual health as the presence or absence of disease — namely sexually transmitted infections. But the WHO defines sexual health as “a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being,” which includes aspects such as reproductive health, access to education and care, and sexual experience free of coercion, discrimination, and violence, among others.2 This emerging, broader conversation around sexual health is rooted in changes in communication — the more we talk about it, the more informed we are. The more informed we are, the more we can reduce the stigma associated with sexually transmitted infections and improve the uptake of testing.

A silent epidemic, but the calls for help grow louder

Sexually transmitted infections are inclusive of viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and parasites people can contract through sexual contact. And many STIs have no symptoms, resulting in asymptomatic infections.3 The burden of STIs in the United States is astounding. One in five people in the U.S. have an STI, equating to 68 million infections4 and $16 billion in direct medical costs per year.5 While it’s true if you are having sex you are at risk, some populations are disproportionately affected by STIs, including young people aged 15–24, gay and bisexual men, pregnant people, and racial and ethnic minority groups.6

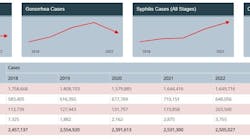

The CDC has recommended that STIs be a top public health priority as rates of many STIs continue to increase7 despite available treatment options. Left undiagnosed or untreated, STIs can lead to harmful and lasting consequences, such as infertility, ectopic or adverse pregnancy outcomes, congenital infection, chronic pelvic pain, increased risk of HIV infection, and psychological harm through stigmatization.5 These consequences are unacceptable in a world where many STIs are treatable.

In 2021, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) launched a first-of-its-kind national strategic plan aimed at reversing “the recent dramatic rise of STIs in the United States.”8 Focused on chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and human papillomavirus (HPV), the plan serves as a roadmap to help federal and non-federal stakeholders at all levels and in all sectors achieve the vision of making the United States “a place where sexually transmitted infections are prevented and where every person has high-quality STI prevention, care and treatment while living free from discrimination.”

This plan’s vision and goals cannot be achieved without the important role of the diagnostics industry — supporting increased screening volumes, developing medically relevant assays and claim extensions, and advancing new technologies to support point-of-care testing, self-collection, and rapid antibiotic susceptibility testing.

STI diagnostics face challenges

Diagnosing STIs is important — because if we test, we can cure or treat, therefore reducing transmission. But challenges remain. Testing underutilization can lead to overtreatment or undertreatment of the infection, and this is if patients even have access to fast and accurate diagnostic solutions. Additionally, similar to respiratory infections, overlapping symptoms among STIs make empirical diagnosis challenging, therefore requiring appropriate diagnostic testing performed in clinical settings.

In a real-world study analyzing more than 23 million instances of patients presenting with symptoms of a urogenital condition, 89% of patients who received antibiotics received their treatment within the first three days of their initial appointment, likely before results from CT (Chlamydia trachomatis)/NG (Neisseria gonorrhea) testing would be available. This data points to presumptive therapies for diseases that should be tested for and treated accordingly, contributing to suboptimal antimicrobial and diagnostic stewardship. Due to the overlapping symptoms and varying treatment pathways across common STIs including CT, NG, MG (Mycoplasma genitalium), and TV (Trichomonas vaginalis), definitive diagnosis is critical to making treatment decisions.9 The study, which analyzed STI testing and treatment patterns in the United States, also showed that fewer than 2 in 10 individuals received CT/NG testing, despite showing symptoms,9 further demonstrating the underutilization of STI testing.

Rapid and accurate STI testing is needed to inform appropriate treatment recommendations and prevent further transmission. And this is where point-of-care testing can emerge to fight this epidemic, providing broader access, faster testing, and a definitive diagnosis in less than 30 minutes.10

How patients can benefit from STI testing at the point of care

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the use of molecular diagnostics at the point of care, allowing the technology to meet evolving customer needs for quick and accurate results, improve the patient diagnostic experience, and increase operational efficiency for providers.

Currently, a majority of STI testing is done in a central lab, with CDC guidelines recommending screening for asymptomatic individuals based on a variety of different risk factors. Given these tests are standard and routine, high-throughput testing is more economical, with up to 96 samples tested at once instead of one every half hour. However, for symptomatic patients in certain settings, STI testing at the point of care allows for a seamless connection of gold-standard molecular diagnostics and treatment. In less than 30 minutes,10 a patient can learn what they may have contracted and how to treat it.

With the closure of STI clinics,11 in addition to changes in how people access healthcare, more patients are using point-of-care settings, such as urgent care, emergency departments, women’s health clinics, primary care physician offices, and public or student health clinics for diagnosis and treatment. In addition to its high specificity and sensitivity across a variety of diseases, molecular point-of-care testing is evolving to meet customer needs, providing rapid results directly at the site of care, and oftentimes, for multiple disease targets in one assay.

Patients can also benefit from the opportunity to receive treatment during the same visit. Using PCR (polymerase chain reaction) technology, previously only used in the lab, molecular point-of-care testing provides the same high level of accuracy as the lab in a CLIA-waived setting,12 offering clinicians a high degree of confidence in diagnosis. This test-to-treat approach can help combat potentially high loss to follow-up rates making treatment more likely and contribute to thoughtful antibiotic and diagnostic stewardship efforts.

Additionally, point-of-care testing has the potential to address barriers in access to care and treatment. By meeting patients where they are, through easily accessed sites of care or organized community outreach, providers have the potential to reach a variety of populations at-risk for STIs, including underserved populations who may have difficulty accessing care or those who face a variety of stigmas and discrimination.

What the future of molecular point-of-care testing means for sexual health

Laboratorians, clinicians and leaders in healthcare settings can also find value in molecular point-of-care testing beyond STI diagnosis. With already FDA-approved, CLIA-waived assays for a range of respiratory infections, an investment in decentralized, molecular point-of-care testing has the potential to meet the same-visit diagnosis demand from patients and alleviate staffing strains due to the simplicity of the tests, freeing up laboratorians to address more complex tasks requiring highly-trained professionals.

To date, there are only two FDA-approved tests to diagnose STIs at the point-of-care, including a CT/NG/TV assay and a CT/NG assay – both of which have limited indications compared to the epidemic the U.S., and the world, are facing. However, innovation in this space is well underway, and I expect one day there is the potential for molecular point-of-care testing to cover the whole spectrum of STIs, including expansion to genital lesions, mpox, causes of vaginosis or even HIV.

By making STI testing more accessible, and therefore immediately treatable, there is an opportunity to stop this epidemic in its tracks. And no matter our role in implementing molecular STI testing at the point of care, let’s continue to speak up and advocate for sexual health for all.

For more information on Roche’s commitment to sexual health, visit https://diagnostics.roche.com/us/en/products/product-category/sexual-health.html.

References

1. Ueda P, Mercer CH, Ghaznavi C, Herbenick D. Trends in Frequency of Sexual Activity and Number of Sexual Partners Among Adults Aged 18 to 44 Years in the US, 2000-2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;1;3(6):e203833. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3833.

2. Sexual health. Who.int. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.who.int/health-topics/sexual-health.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STDs - Diseases & Related Conditions. cdc.gov. Updated July 7, 2023. Accessed March 26, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/general/default.htm.

4. Diseases & related conditions. Cdc.gov. Published July 7, 2023. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/std/general/default.htm.

5. CDC. STI prevalence, incidence, and cost estimates infographic. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published January 25, 2021. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/prevalence-2020-at-a-glance.htm.

6. The state of STIs - infographic. Cdc.gov. Published December 19, 2023. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/infographic.htm.

7. Sexually transmitted infections surveillance, 2022. Cdc.gov. Published January 29, 2024. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/default.htm.

8. Office of Infectious Disease, HIV/AIDS Policy (OIDP). STI national strategic plan overview. Hhs.gov. Published June 19, 2019. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/programs/topic-sites/sexually-transmitted-infections/plan-overview/index.html.

9. Lillis R, Kuritzky L, Huynh Z, et al. Outpatient sexually transmitted infection testing and treatment patterns in the United States: a real-world database study. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;13;23(1):469. doi:10.1186/s12879-023-08434-2.

10. Point of care tests. Who.int. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research-%28srh%29/areas-of-work/sexual-health/sexually-transmitted-infections/point-of-care-tests.

11. Blachford A. The rising importance of urgent care in the fight against the STI epidemic. Journal of Urgent Care Medicine. Published November 30, 2022. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.jucm.com/the-rising-importance-of-urgent-care-in-the-fight-against-the-sti-epidemic/.

12. Hansen G, Marino J, Wang ZX, et al. Clinical Performance of the Point-of-Care cobas Liat for Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in 20 Minutes: a Multicenter Study. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;21;59(2):e02811-20. doi:10.1128/JCM.02811-20.